Hundreds of thousands of people see inside the places and spaces where we lock up young members of our society. On any given day, more than 60,000 children in the United States are behind bars. They are joined by guards, counselors, volunteers, educators and medical staff.

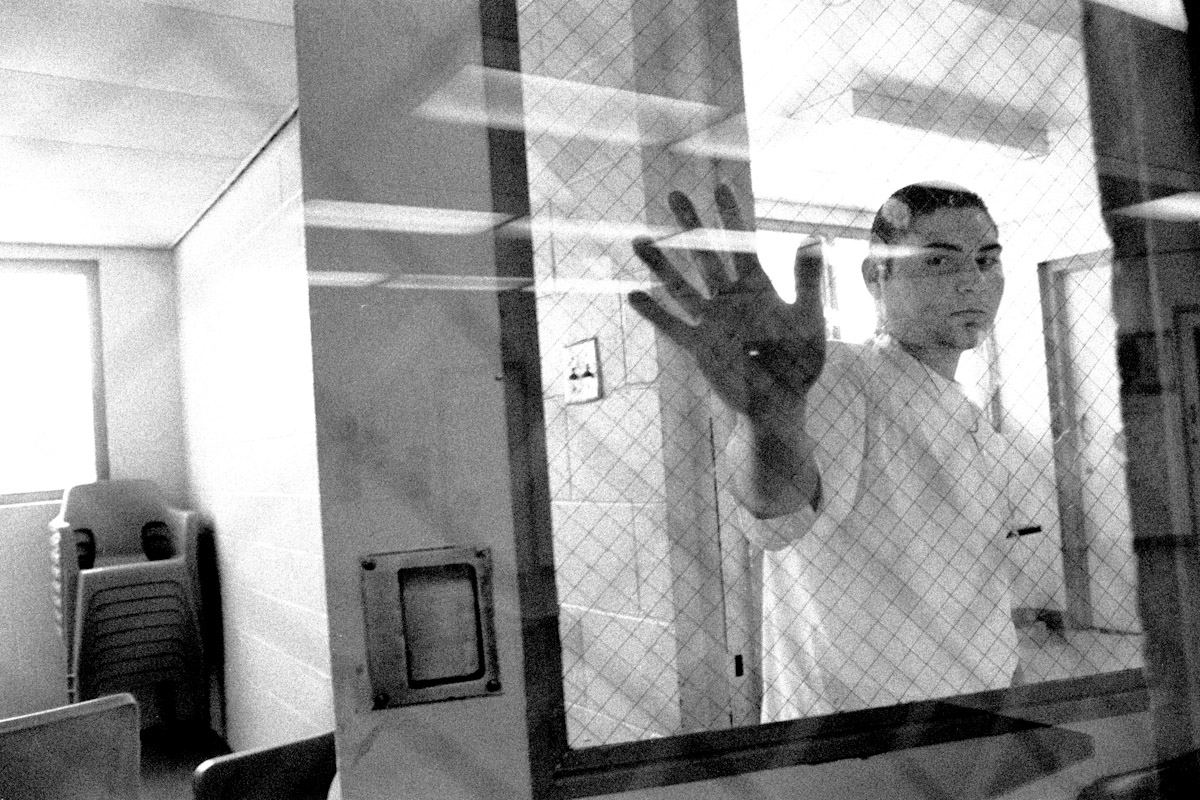

Journalists go into some juvenile detention facilities often, and into other facilities rarely, if ever. Phone calls may be made, stories may be told, letters written, letters read, but with the exception of digital keepsake photographs taken in visiting rooms, photographs of juvenile detention are few and far between.

A photographer leaves a prison or jail with a different type of memory. A memory divided by emotional memory and visual memory.

The emotions of their experience are, in the case of photographers Steve Davis, Joseph Rodriguez and Ara Oshagan, quite profound. Their visual memory is one shaped by living with the photographs they made and now share.

Joseph Rodriguez

“Once you’re an addict you’re always and addict,so you don’t forget what those experiences are about. I mean you can; you try to,” says Joseph Rodriguez, a New York-based documentary photographer who made images inside the San Francisco County Juvenile Hall in the summer of 1994.

Rodriguez, age 60, has photographed across theglobe, but he is most well-known for his images of social exclusion, community, struggles and success in America’s cities. He grew up in the 1950s and ‘60s in a New York neighborhood susceptible to the long reach of the law. Between 1968 and 1970, Joseph spent two stints inside Rikers Island Jail.

Rodriguez, age 60, has photographed across theglobe, but he is most well-known for his images of social exclusion, community, struggles and success in America’s cities. He grew up in the 1950s and ‘60s in a New York neighborhood susceptible to the long reach of the law. Between 1968 and 1970, Joseph spent two stints inside Rikers Island Jail.

He started photographing shortly after his second time at Rikers. “As a child I felt powerless,” he says. “What photography does for Joe? It gives him power. But with that power comes responsibility.”

In the mid-1990s, then in his mid-40s, Rodriguez realized his responsibility was to connect with children who were not too unlike his younger self. He followed a number of teenagers with his camera, not only through juvenile detention but also through arraignment, court, programs, imprisonment and in free society.

Steve Davis

A few years later, and a few hundred miles north, up the West Coast, Steve Davis began making portraits in four Washington state juvenile facilities and running photo workshops with the teenagers. Davis’ photographs and the photographs of his students were created over an eight year span (1997 to 2005).

“The motivation from these kids to have their picture taken was overwhelming. They all knew that their portraits were to go into a catalog, and that the photos would be published and shown. …They had a story to tell, and they had an audience,” Davis explains.

overwhelming. They all knew that their portraits were to go into a catalog, and that the photos would be published and shown. …They had a story to tell, and they had an audience,” Davis explains.

Davis says he quickly realized that many of the students had rarely completed a project of any description. “Photography was secondary,” he recalls. “They just needed something to do as a group that might actually have some kind of consequence.”

But he was most affected when photographing in the Intensive Management Unit (IMU). “I explained I really needed to take pictures of the IMU and that I didn’t want to make it pretty. The administrator said ‘Yes,’ which really blew me away,” Davis recalls. “It was the most inhumane living environment I ever witnessed.”

The IMU was usually locked down and “usually off limits,” Davis says. The IMU staff was just excited that someone else was visiting.

The sharp-end of Davis’ visual memory is the hatches in the cell doors.

“It is where [the kids would] get their food, mail and medical needs. That’s when the IMU really started to affect me emotionally. When I was working with them face-to-face in these institutions it wasn’t any different to working with kids anywhere,” Davis says.

Ara Oshagan

As a resident of Los Angeles, Ara Oshagan was aware of California’s bloated prison and jail systems, but an invitation to shoot B-roll with a documentary film crew in Los Angeles Central Juvenile Hall gave him the opportunity to be a firsthand witness to one of the largest youth detention centers in the nation.

Rather unexpectedly, Oshagan felt he often got in the way of his own image-making. During the years he visited the jail and others, it vexed him that his photographs could never quite capture the teens’ “true” experiences. He had to, in some way, give over his photographs to the young people. In diptychs he combined his images with their written words.

Rather unexpectedly, Oshagan felt he often got in the way of his own image-making. During the years he visited the jail and others, it vexed him that his photographs could never quite capture the teens’ “true” experiences. He had to, in some way, give over his photographs to the young people. In diptychs he combined his images with their written words.

“The texts that I combined with my photos give a much deeper sense of incarcerated life. That is because they are authored by the youth themselves,” Oshagan says.

Oshagan believes his images show the horrors of incarceration but remain “the photographer’s experience of that reality translated into image.”

“A truly candid photo is a near impossibility in prisons or juvenile halls. By the very nature of the situation inmates are in, they allow for very few unguarded moments. And as a photographer you have very little time to take photos,” says Oshagan, who followed some of the teens who were sentenced into jail, camp, and in some cases adult state prison.

Ultimately, Oshagan was most disconcerted by his realization that his own children are not too dissimilar to those locked up in his photographs.

Perhaps with his, Davis’ and Rodriguez’s photographs we can now see how children in these “exposed” and “watched” spaces, as Davis described them, are not too different from our own.

View the entire photo spread here.

Pete Brook covers art and photography for Wired.com’s Raw File blog. He also writes and edits “Prison Photography.” He lives in Portland, Ore.