As a growing number of states ban or further limit abortion in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in June, women in many places face increasing barriers to seeking abortion. But for teenagers and young people in foster care or those who have recently aged out, the new restrictions are making abortion access, already a challenge, even more difficult.

Foster youth are more likely to become pregnant than their peers and less likely to have financial resources and a family support system. An American Academy of Pediatrics study found that half of children born to teens in foster care ended up in child protective services custody by their second birthday.

M., who is now in her late twenties, spent more than a decade in foster care. (Youth Today is identifying her by her first initial to protect her privacy.) Last year, in her late twenties, she learned she was pregnant, just days before a Georgia law significantly limiting abortion took effect, and weeks later sought an abortion for medical reasons.

Getting an abortion was a daunting process, which she navigated with the help of friends and family members as well as organizations that had supported her while in foster care, she said. She eventually obtained medication to end her pregnancy by having it delivered to an address in another state.

If she was still in foster care at the time, the situation would have been very different, she said.

“Many young adults, or young kids that are pregnant and in foster care, don’t have the type of network and connections that I have at this period in my life, so I can only imagine where this would’ve stopped if I was still in foster care,” she said.

Challenges to access

Access to abortion has never been easy for young people in foster care, said Alina Salganicoff, director of women’s health policy at Kaiser Family Foundation, an independent health policy nonprofit.

“You’re talking about a population that’s disproportionately covered by Medicaid in many states,” Salganicoff said. And Medicaid, the nation’s public health insurance program for low-income people doesn’t pay for abortion because of the Hyde Amendment, which blocks federal funds from being used to pay for abortion, she said.

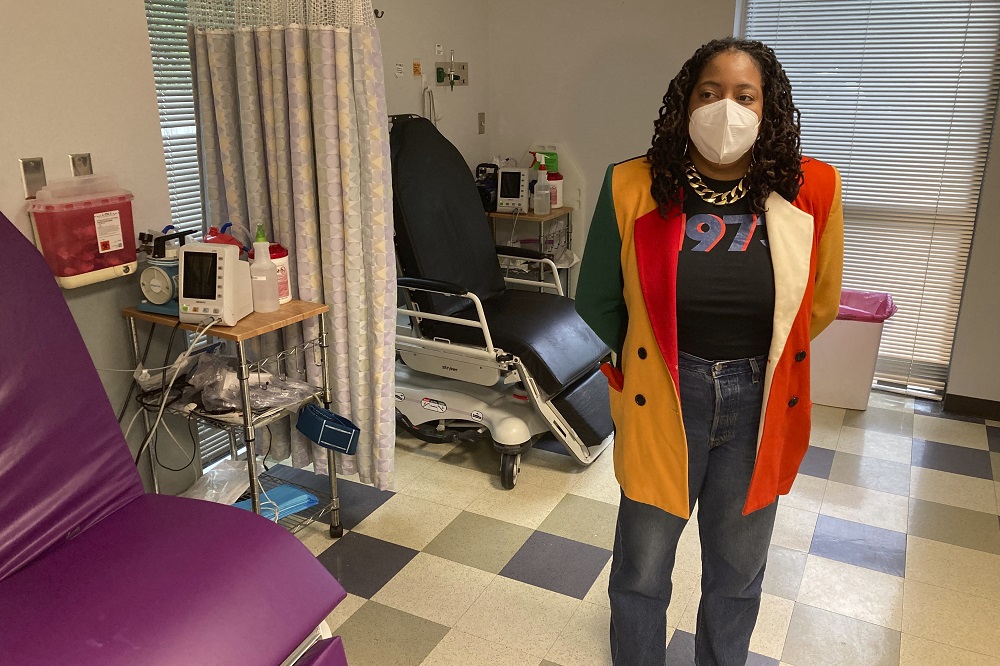

Courtesy of Alina Salganicoff

Alina Salganicoff, Kaiser Family Foundation

This means that foster youth seeking abortions must pay for abortions themselves, a challenge for teens with limited income and often a more limited family network to borrow from. Depending on the method and how far along into pregnancy one is, the procedure can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars without insurance.

Currently, 36 states require parental involvement in a minor’s decision to have an abortion. Those laws are often more difficult for young people in foster care to navigate than their peers.

In most states where parental notification or consent is required, caseworkers are prohibited from consenting to an abortion or from providing notification for an abortion, said Ellen Friedrichs, a New York-based health educator.

In most of those states, the only way a minor can obtain an abortion is by judicial bypass, or obtaining a judge’s permission for an abortion. (This isn’t true for all states: In Massachusetts, for example, a person under 16 can now get permission for abortion from a parent even if in the custody of the state welfare agency, said Jamie Sabino, deputy director of advocacy at the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute.)

Natasha Moustache/Courtesy of Jamie Sabino

Jamie Sabino, Massachusetts Law Reform Institute

But “even if a teen goes before a judge there is no certainty that they will be allowed to obtain the procedure,” Friedrichs said.

Going before a judge is particularly hard, emotionally, for many foster youth, Sabino said. And a disproportionate number of young people doing so are “kids of color or poor kids,” she said.

“Court is the site of some of the worst things that have happened to them, so it’s incredibly traumatic,” she said. “It also is logistically difficult. Besides not wanting to tell their parents what they don’t have to do, they don’t want to tell their … social worker. They don’t want to tell their foster parents because they might lose their placement.”

It is also difficult for foster youth to miss school in order to get a judicial bypass.

“Foster youth are surveilled in a way that [other] teenagers aren’t,” Sabino said.

“I didn’t know about my body”

Brittney Lee, a 28-year-old living in Tacoma, Washington, had an abortion at 19, shortly after aging out of the system. Lee had lived in 17 foster homes since first being placed in foster care at age two, but found that in the home they lived in for the longest, they were not taught about comprehensive sexual education.

“The most that I heard from [my foster mother] was that ‘if you get pregnant, you’re getting kicked out.’ They didn’t even teach me how to use menstrual products,” Lee said of the foster home where they lived the longest.

“I was painfully lacking in [reproductive health] education; there was so much I didn’t know about my body,” they added. “You learn a lot in school informally, but that’s not the best source and sometimes it was my only source on sex and sexuality.”

Courtesy of Brittney Lee

Brittney Lee lived in 17 foster homes since first being placed in foster care at age two.

Less than a third of teens in foster care received information on birth control and family planning, according to a 2005 study of 17- and 18-year olds who were or had been in foster care in the Midwest.

“The most that I heard from [my foster mother] was that ‘if you get pregnant, you’re getting kicked out.’ They didn’t even teach me how to use menstrual products.”

By their mid-twenties, nearly 80 percent of the young women in that same study had been pregnant at least once, compared to 55 percent of peers who had not been in foster care.

And about three-quarters of the former foster youth said their last pregnancy had been unplanned, compared to just over half of their peers. Former foster youth were also less likely to report that their last pregnancy had been terminated.

“These young people often have a lot of instability in their lives because of placement changes and school changes, and so they may just totally miss out on any sexual education that’s taught in schools,” said Amy Dworsky, a senior research fellow at Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago and an author of the 2005 study. “If you move at the wrong time, you’re gonna miss that unit.”

And young people in foster care, even more so than other kids or teenagers, might not have an adult they feel comfortable talking to about reproductive health.

“They may not feel comfortable having that conversation with a case worker who they barely know, or with a foster parent who they’ve only been with for a few months,” Dworsky said. “So they may just not have someone they can ask about birth control or the risks of pregnancy.”

***

Houreidja Tall is a New York City-based journalist.