When Jane Quinn walked into the gleaming conference room at the Carnegie Corporation of New York in 1990, its wide bank of windows letting in the sunlight, she was pretty sure what to expect. A governor, a school superintendent and a couple of Yale and Stanford professors awaited her, along with a committed philanthropist and leaders of national organizations dedicated to youth.

What surprised her was how little was known about the subject they had all come to inquire into: the impact of youth-serving organizations.

Jane Quinn

After more than a year of work, the illustrious group released its findings — and then sat back and watched its impact take shape. It was a report that shifted youth work in the United States, according to the participants. “A Matter of Time: Risk and Opportunity in the Nonschool Hours” pointed out how the hours outside of school provided a major opportunity to address some glaring needs of young people.

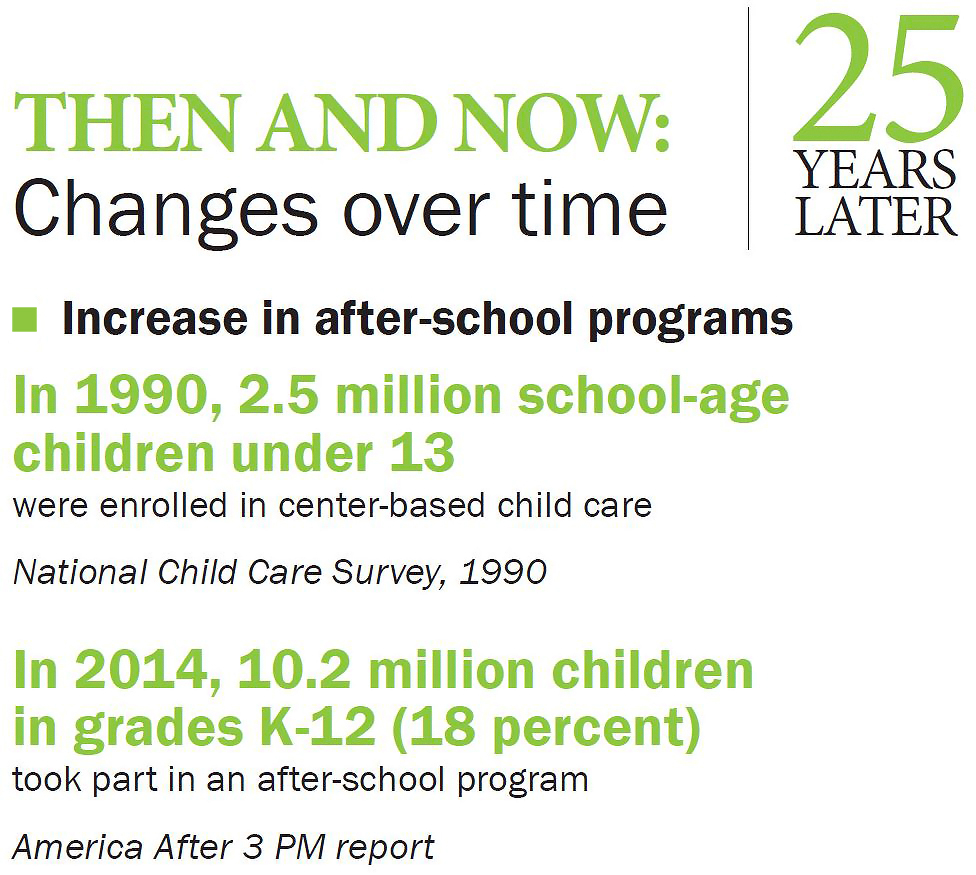

Today, in contrast with the 1990s, low-income kids have far more access to after-school programs through a plethora of national and community organizations. Today, youth work is focused on building the strengths and abilities of all young people, and meeting their developmental needs rather than being limited to specific problems such as teenage pregnancy or juvenile crime.

There’s an understanding that schools, after-school and various youth services need to work together, and many national funders are committed to supporting their work.

The crack cocaine era

Quinn, today a vice president at the Children’s Aid Society, was a newly hired project director at the Carnegie Corporation in 1990. She led the Carnegie Task Force on Youth Development and Community Programs.

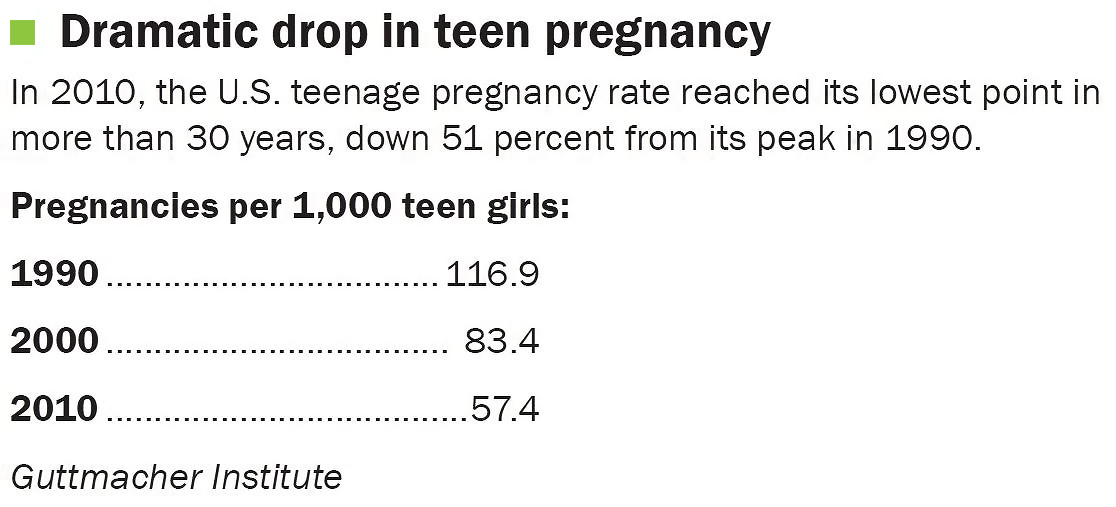

At that time, Phil Coltoff was president and chief executive of the Children’s Aid Society. He recalled the 1980s and 1990s as the time of a crack cocaine epidemic, an onslaught of pediatric AIDS and an extremely high rate of unwanted teenage pregnancies. At the time, the high school dropout rate was as high as 35 percent for some groups such as Hispanic students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Unemployment of African-American youth reached 45 percent in 1993, according to the Federal Reserve Bank.

At that time, Phil Coltoff was president and chief executive of the Children’s Aid Society. He recalled the 1980s and 1990s as the time of a crack cocaine epidemic, an onslaught of pediatric AIDS and an extremely high rate of unwanted teenage pregnancies. At the time, the high school dropout rate was as high as 35 percent for some groups such as Hispanic students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Unemployment of African-American youth reached 45 percent in 1993, according to the Federal Reserve Bank.

Coltoff, who was a member of the Carnegie task force, is today a senior fellow at the Silver School of Social Work at New York University.

“My sense at the time of the report was that there was a real concern around the country, partly in youth-serving organizations and in government … that the major youth-serving organizations were not reaching the most needy and vulnerable,” he said.

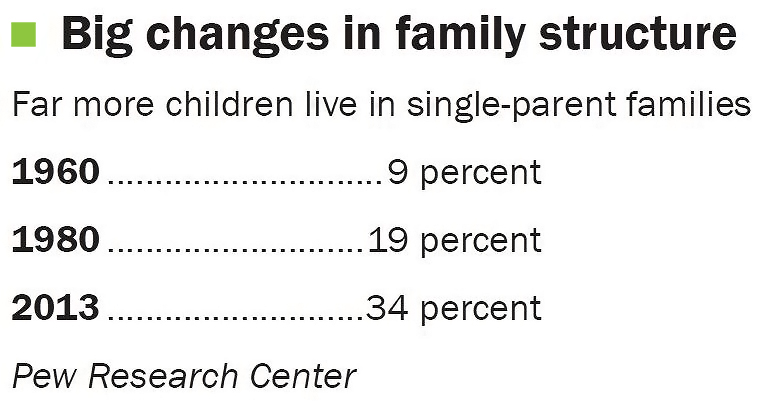

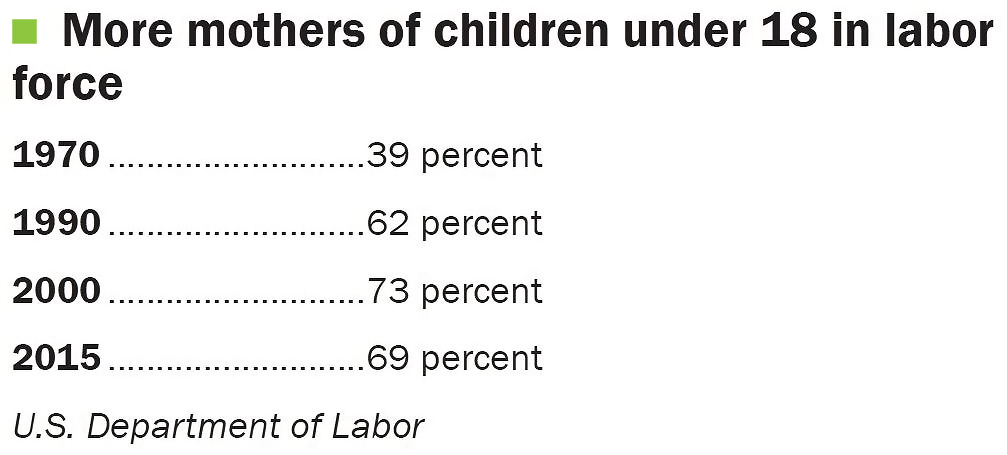

More than 60 percent of mothers had joined the labor force, and the word “latch-key kid” was often heard.

“Gang activity was re-emerging,” Coltoff said.

Karen Pittman, now co-founder, president and CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment, was also on the task force.

Karen Pittman, now co-founder, president and CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment, was also on the task force.

“There was an increasing realization that young people were at risk in the out-of-school hours,” Pittman said.

“As a country we weren’t providing [all that much] for families to find care for children when they were working,” she said. “Juvenile crime was being linked to lack of supervision.”

Pam Stevens, a New Orleans-based grantmaker and youth development consultant, worked at the Wallace Foundation at the time. She remembered that kids in low-income neighborhoods had relatively few organized after-school activities, aside from church and possibly local parks and recreation departments.

Youth organizations under the microscope

The Carnegie Task Force on Youth Development and Community Programs looked carefully at youth organizations, including Scouting, the YMCA, settlement houses and church-run youth services, Coltoff said.

The Carnegie Task Force on Youth Development and Community Programs looked carefully at youth organizations, including Scouting, the YMCA, settlement houses and church-run youth services, Coltoff said.

“What we found was that very often

they were not necessarily well-used by youth,” he said.

The YMCAs, for example, were serving seniors, preschoolers and some elementary-age children, and were also functioning as a fitness center, he said.

“Organizations were not committed to teens and young adults,” he said. They had basically become health clubs and fitness centers.

Boy Scouts of America had a limited reach, Coltoff said: “Scouting had become a white middle-class and upper-class phenomenon.”

Coltoff and Quinn met Boy Scout leaders at the Dallas airport. They urged the Scouts to expand into urban areas and to operate in community centers and schools.

Task force members met with YMCA leaders in Chicago and pointed out some shortcomings.

Task force members met with YMCA leaders in Chicago and pointed out some shortcomings.

“Teenagers are most available in the early evenings, but the Ys were closing at 6 p.m. and were unavailable for athletic groups or social clubs,” Coltoff said.

The YMCA was responsive, he said. It set up a task force on urban youth and black males, among other things. “They changed their direction and altered their mission,” Coltoff said.

Making a case

“A Matter of Time: Risk and Opportunity in the Nonschool Hours” noted that millions of young adolescents in low-income rural and urban areas were not being served. It called on community organizations to move beyond addressing single problems. It recommended that organizations tailor their programs to the needs and interests of young adolescents, respond to their experiences and enhance their role as resources in their communities.

It urged funders to work in partnership with youth organizations, and it urged local, state and federal governments to coordinate their policies.

The report helped pave the way for Congress to create the 21st Century Community Learning Centers initiative that now provides after-school programs for 1.6 million youth in high-poverty areas, according to Quinn.

The report helped pave the way for Congress to create the 21st Century Community Learning Centers initiative that now provides after-school programs for 1.6 million youth in high-poverty areas, according to Quinn.

“A Matter of Time” was championed by U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno, who pushed the value of after-school programs in speeches to organization such as the National Crime Prevention Council.

“I think it changed the public conversation about the nonschool hours into a risk-opportunity framework,” Quinn said.

The task force unearthed the 1988 research of Reginald Clark showing that young people living in low-income communities perform better academically than their peers when they have 20 to 35 hours of nonschool learning activities, such as reading for pleasure, and playing strategy or word games.

It showed the value of practicing academic skills through nonacademic activities, Quinn said.

“Now most youth organizations understand that they have a complementary and supplementary role to play around academic success,” she said.

Then and now

After-school providers were able to arm themselves with research when they went to funders and communities to argue the importance of their work. “We gave people data on the equity issue,” Quinn said.

The 1990s approach to after-school was that it was nice but not necessary, Pittman said.

“We are in a very different place now,” she said.

“We actually have after-school systems now in cities and counties,” she said. Standards and training have been developed, and funders are supporting this, she said.

Stevens, the consultant to funders and youth organizations, said the ideas of positive youth development were not widely appreciated in the 1990s.

“‘A Matter of Time’ helped pull together in one place a lot of information to help us talk about positive youth development,” she said.

The important idea, Stevens said, is that “you can help kids develop in different ways, whether they have a problem or not.”

The Wallace Foundation used the report to undergird its positive youth development work, she said.

“Other funders did that, too,” she said. “It was such a pivot in a way of thinking from a problem-centered to a holistic approach.”

Public funding has increased. In addition to federal money, states such as California, Oregon and Washington are using tax dollars to support positive youth development, she said.

And a body of research lacking in the 1990s has now grown.

“Research has now shown that kids in quality youth development after-school programs get positive outcomes,” she said.

Stevens sees more work across different sectors now. For example, a young person at a recreation program might get referred to a youth-employment organization.

“Organizations and programs talk across these lines,” she said.

“More and more schools are joining forces with traditional youth-serving organizations and inviting them in as partners,” she said.

“We’ve made lots of strides,” Stevens said.