Keymar, Md.—The setting is pastoral: a 120-acre estate in central Maryland, where Preakness and Kentucky Derby winners were once raised.

But the outcome was the ultimate nightmare for youth workers: The death of a youth in their care.

About six times a year, a young person dies at a youth agency the way Isaiah Simmons died at the Bowling Brook Preparatory School: at the hands of youth workers trying to restrain him.

In this case, however, the 17-year-old’s death on Jan. 23 unleashed forces that delivered an unexpectedly harsh blow: the shutdown of a 50-year-old school for adjudicated youth that was so well-regarded that the state was helping it grow.

Bowling Brook was in the final stages of major expansion and a $2.4 million building program, fueled in part by $1 million in grants from the state Department of Juvenile Services (DJS), which sent youths to the staff-secure facility and monitored it.

At 8:15 one night, everything changed.

|

|

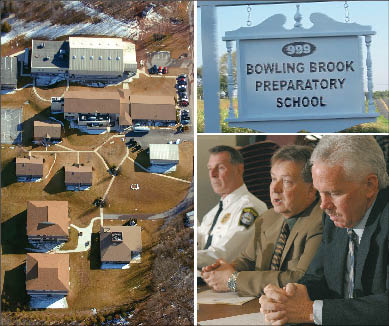

Tragic news: Carroll County State’s Attorney Jerry F. Barnes, center, announces indictment of staffers in the death of a boy at Bowling Brook Preparatory School. Photo: Sign: Bowling Brook / Other photos Courtesy of The Baltimore Sun Co. All Rights Reserved. |

Work on a new on-campus vocational center halted, and all but five of 90 Bowling Brook workers were soon without jobs.

Bankers threatened to call in on loans that had helped finance the new construction.

And last month, six Bowling Brook youth workers were indicted for reckless endangerment. They face up to five years in prison.

The death also forced DJS to change its policies on staff training and restraints, especially to fill a gap involving private institutions that might exist in other states as well.

For all of its drama, the Bowling Brook disaster is about something that’s considered rather dry: staff training. It offers a stark warning about what can happen when the staff isn’t properly trained on how to restrain youth, or when staffers don’t heed the training.

A Rising Star

State officials viewed the nonprofit Bowling Brook as a success in handling troubled youths like Simmons, who had been at the school only two weeks after being convicted of a robbery in downtown Baltimore.

“I have advocated for kids to go to Bowling Brook repeatedly,” says state Deputy Public Defender Michael Morrisette. “It had a reputation for being one of the finest places, especially in light of the alternatives.”

In a state where the harsh treatment of youth at juvenile boot camps and lousy conditions at state-run juvenile correctional facilities regularly made news, Bowling Brook was a breath of fresh air. Other states, including Pennsylvania, also sent youths there.

The facility, not far from the Pennsylvania state line, had grown from fewer than 40 youths before 2001 to 170 this year. The school was praised by then-Gov. Robert Ehrlich (R) for its performance, and by nearby residents for the youths’ volunteer work for local charities. The youths had helped the Westminster Boys & Girls Club move to a new site, and they regularly served customers at local pancake breakfasts and chili cook-off fundraisers for local agencies.

“Everyone noticed how polite they were,” says Tom Willover, a Winchester resident and frequent volunteer who helps run a Baltimore real estate firm. “They did it with a smile. I don’t think you can force kids to behave that way.”

Bowling Brook says that almost four out of five youths earned high school diplomas while at the school; in 2006, 159 students graduated. Of these, the school says, 49 percent were accepted to a college or technical school, 35 percent got jobs and 16 percent went to community-based education or apprenticeship programs.

Confrontation Encouraged

School officials say their success centered on a philosophy that enlisted peer pressure to foster good behavior and manners. A PowerPoint presentation used in staff training emphasizes that the concept “relies on confrontation – thousands each day to sustain its normative culture. The school’s locks and bars are replaced by … tools of behavioral change and control,” namely confrontation, peer pressure and expulsion.

“Confrontation is the most direct and impacting” of the tools, the presentation says. “Our job is to interrupt dysfunctional behavior both subtly and abruptly.”

The approach “is a bit confrontational,” says Bruce Chapman, who visited Bowling Brook shortly after Simmons’ death. Chapman created Handle With Care, a widely used crisis intervention system.

“There’s a slightly blurred distinction between kids and staff,” Chapman notes. “Kids are used to keep applying peer pressure.

“Staff and kids eat together. You see politeness: Kids walk up to strangers and say hello, and yet everything in that program is designed to deal with the most hardened kids.”

The Tragedy

The trouble on Jan. 23 began at about 4:45 p.m., just before dinner. By 8:15 p.m. Simmons lay lifeless.

The school’s report to DJS offers the most detailed account available. The one-page document is filled with the type of lingo about peer relations and confrontation that’s found in the staff training materials.

It says Simmons “was in a conversation with another student, when [he] stated that if his house peers corrected or confronted him, he would not accept this help, but would rather ‘spaz out.’

“Dennis H [apparently Dennis Harding, one of the indicted counselors] became involved by questioning the statement, asking for clarity around the meaning of his words. [Simmons] communicated that he would fight, if not ‘shoot’ another student.”

|

|

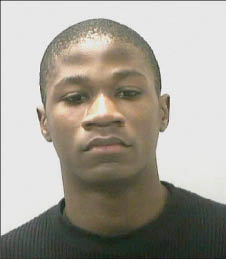

Simmons “was not a threat to himself or others,” says the head of the Juvenile Protection Division. Photo: AP Image |

The report says staff determined from Simmons’ “body language” that he intended to escalate the incident in front of “his peer group.” When he made “a sudden movement with his hands and arms,” Harding placed him in a one-man seated upper torso restraint position.”

The time frame for what followed is not clear. Another counselor replaced Harding in the restraint and rolled Simmons to “a more restrained prone position.” Three more staff members joined in the prone restraint, “attempting to redirect the student from a relationship of influence.” More staffers eventually “rotated” into the restraint.

At one point Simmons “spoke of his daughter, his absent father and the home life from which he came.”

Workers stood Simmons up, but he tried to pull free and was “again lowered to the floor” in a prone position. He continued to struggle.

Then comes this paragraph:

“Seeing how negative attention was reinforcing him, staff switched the focus off of the restraint and onto other topics. There in time [Simmons] stopped struggling and became nonresponsive. The collective thinking of staff and intervening students was that [he] was feigning sleep.”

This moment appears key to the charges the six employees now face.

Swift Sentence

The state medical examiner determined that the cause of death was “sudden death by restraint.”

The workers had waited a while before calling an ambulance. “A call should have been placed to 911 about 41 minutes before it occurred, and they [the staffers] had a duty to do so,” Carroll County State’s Attorney Jerry F. Barnes said at a news conference in April. “That’s the essence of the charge.”

Reckless endangerment is a misdemeanor in Maryland.

The action against the facility came much faster.

Bowling Brook “didn’t expect we’d be shut down,” says Program Service Director Brian Hayden. “Looking at similar situations where there were deaths, they made changes and seemed to come out a little stronger.”

One key difference was that Maryland had a new player in such cases: the Juvenile Protection Division of the Maryland Public Defenders Office, headed by attorney Deborah St. Jean.

Soon after the death, state investigators, led by St. Jean’s staff, went to court to remove DJS clients from Bowling Brook. The school forfeited its license to operate on March 9, just six weeks after Simmons’ death.

The youths were sent home or to other schools.

St. Jean calls the restraint of Simmons “torture” and says “they crushed the breath of this kid over an extended period of time.” She charges that other youths at Bowling Brook had been improperly restrained as well.

How to Restrain

For many youth advocates and experts in crisis intervention, Bowling Brook appears to be a case study in what not to do.

“I’m angered that organizations aren’t learning anything,” says Cornell University’s Martha Holden, director and co-developer of the widely respected Therapeutic Crisis Intervention (TCI) program. “It’s the same thing over and over.”

One Washington state activist who started her own group, The Coalition Against Institutionalized Child Abuse, lists 68 restraint deaths since 1988, including six last year and three this year.

How to properly restrain out-of-control youths – or even whether to do so – is a difficult and sensitive issue, with restraint philosophies and training continually evolving and sometimes conflicting. (See “Fatal Hugs,” September 1999.)

Bowling Brook’s Hayden, an attorney, insists that appropriate procedures were followed in the Simmons case.

One glaring element of the tragedy was the lengthy duration of the restraint: It went on for hours.

“I just can’t fathom somebody being out of control that long,” Holden says. “That in itself is a huge red flag.”

Deaths “tend to happen during long restraints,” says Joseph K. Mullen, president of JKM Training, based in Carlisle, Pa., and creator of the Safe Crisis Management system.

Mullen says Bowling Brook sent some staff members to one of his training institutes about five years ago, and “we were in the process of negotiating about possible training [there] when the school closed.”

Mullen recommends limiting prone restrains to five minutes and all restraints to 10 minutes.

Face-down prone restraints are particularly dangerous; they can they can lead to fatal “positional asphyxia.” Critics of restraint use say the tactic should never be used, although some trainers say it can be done safely.

“Face-down is not the issue. Chest compression is the issue,” Chapman says.

Robert Watters, executive director of Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI) in Brookfield, Wis., emphasizes getting the person off the floor as soon as possible. “Any time an individual is put on the ground, you increase the risk factor,” he says.

Another crucial element during a restraint, Chapman said, is to “continually monitor the physical and emotional safety of the kid. … It’s not some minor oversight if you overlook that a kid has stopped breathing.”

Regardless of the training philosophy, perhaps the biggest issue is whether the staff members apply it. That can be a function of how thorough their training was and how often they got refreshers. In fatal cases, Holden says, “almost always there is a misapplication of techniques” by staff.

For all youth agencies, the question is: What kind of training is correct and how much is enough?

Training Choices

There are many ways to fulfill staff training requirements, some taking more time and money than others. An agency can contract with one of several established programs, or – if government oversight allows – devise its own approach, which might be a risky choice.

Chapman says Bowling Brook used its own “hybrid” system of training and restraints that incorporated elements of several commonly used systems. It was “a program of their own construct,” he says, “but it wasn’t unreasonable.”

Documents and logs indicate that Bowling Brook’s staff training in de-escalation and restraint involved four hours of theory and four hours of practice, according to David P. Daggett, chief deputy state’s attorney in Carroll County, Md.

“That’s nothing,” Holden says. “We use five days of training” in the TCI system. “I don’t know any programs that are less than three days. You can’t learn the physical skills [for restraints] in one day. There has to be teaching and practice, teaching and practice.”

Then training must continue, Mullen says. “It comes down to the supervision of direct-line staff, coaching them up skill-wise after their training and correcting mistakes that show up.”

One criticism of teaching youth workers how to restrain youth is that it might encourage them to do just that. “The best restraint is self-restraint in having to put your hands on someone,” says Watters. “The safest restraint is no restraint at all.”

But at Bowling Brook, “They were restraining kids daily,” St. Jean says. “A number of them endured the exact same treatment. It’s appalling to me that these kids were treated that way.”

It turns out that officials had been concerned about restraint use at Bowling Brook, according to DJS documents. During a September 2005 site visit, DJS monitors found that five of eight Bowling Brook youths interviewed said they had been restrained at least once. One said he was restrained for “an ugly scowl.” The boy said that when staffers told him to “fix his face,” and he didn’t, he was “held down for what seemed like 30 minutes while … staff yelled at him.”

Another youth said he was restrained because “staff did not like the tone of his voice” when he was confronted about writing to his grandmother that he wanted to leave, according to the documents.

None of those youths was injured, the monitor wrote, but he advised that DJS and Bowling Brook officials “discuss what DJS deems appropriate/acceptable reasons for restraining youth.”

In August 2006, Bowling Brook nurse Janis A. Miller contacted DJS after she was reprimanded for calling an ambulance to take a 17-year-old to the emergency room after he’d been restrained by staff.

“My only concern is for the students and their well-being,” Miller wrote to DJS. “I could not live with myself if something happened to one of them that could permanently disable or cost them their life.”

Miller got no reply. “It was unconscionable that that type of report should not have resulted in an inspection,” says DJS Secretary Donald DeVore, who took office after Simmons’ death.

Miller left Bowling Brook. In December 2006, DJS monitors interviewed 10 youths there. Five reported being restrained at least once. “No major injuries were reported,” the monitor wrote.

The Aftermath

Some think Bowling Brook got a raw deal. “It seems like an overreaction,” says Willover, the Bowling Brook neighbor who works in real estate.

“It’s a monumental case of throwing the baby out with the bath water,” Chapman says.

St. Jean’s response: “I did – ethically, morally and professionally – what I was supposed to do,” meaning to get youths who wanted to leave Bowling Brook “in front of a judge.”

Hayden remains optimistic about the future of Bowling Brook. “We’re closed, and we don’t have an operator’s license. But it would be a shame to waste this campus.”

For youth agencies that think they’re safe, Chapman asks a chilling question about the impact of one mistake: “How do you go in two weeks from being a premiere agency to being closed down?”