As COVID-19 outbreaks continue to prompt some school districts, as need be, to teach remotely, Leah Moore is among parents with mixed feelings about the impact of learning from a distance on her own children.

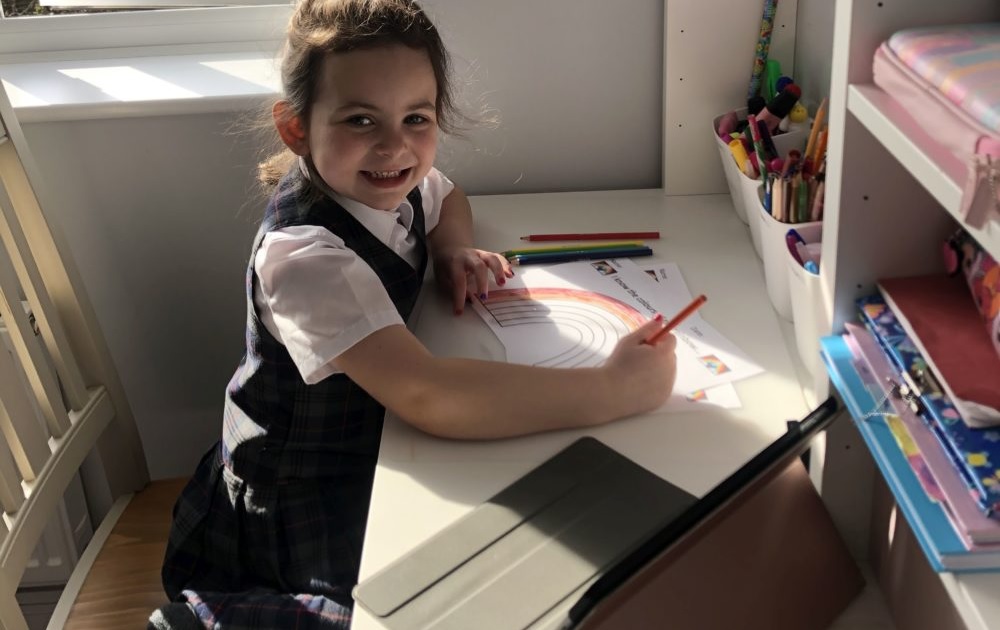

Her local district, the former New York State Teacher of the Year said, did a good job transitioning to remote learning at the height of the pandemic. But, she said, her children Jordan Moore, a 10-year-old with Cri-du-chat syndrome, and Austin Moore, a 6-year-old with a learning disability, are better served by in-person learning, given the support services they get as part of their individualized education programs.

“And,” their mother said, “they also need redirection every few minutes, which is harder over the computer.”

“And,” their mother said, “they also need redirection every few minutes, which is harder over the computer.”

Jordan and Austin diverge on which mode of learning they prefer.

“I like going in-person because I don’t have to just sit there,” said Austin, who finds staring at a screen challenging and likes the social interaction of being in a school environment.

His sister Jordan, who is intellectually and cognitively disabled, enjoys the comfort of learning from home, including studying while in her pajamas.

“I loved it,” she said.

Given the needs of, among others, comparatively more impaired learners such as Jordan, some advocates of students with disabilities are hoping lawmakers and educators will do more to ensure that remote learning is a more permanent option. Thus far, they’ve had mixed success.

On Sept. 9, Texas Gov. Greg Abott signed into law a measure to fund remote learning until 2023, but only for students who pass state exams.

In New Jersey, more than 27,000 people have signed a petition aiming to persuade Gov. Phil Murphy to reverse his plan to restrict virtual learning indefinitely.

“For many of us, remote learning best meets the needs of our children,” reads the petition, created by New Jersey Parents for Virtual Choice. “Many of us don’t want to ‘return to normal’ because ‘normal’ wasn’t working for our kids.”

Overall, math skills fell, while absenteeism rose during remote learning

A Rand Corp. analysis of the 2020-21 school year found that 46% of principals of fully in-person schools and 74% of principals in fully remote settings reported that their students were falling behind in math proficiency. In addition, teachers’ estimates of absenteeism and missed assignments were twice as high in remote settings as in fully in-person ones.

Nevertheless, according to Burbio, which aggregates school information and events, more than 66% of the nation’s 200 top-ranked school districts allow some form of virtual learning. The Associated Press reported in August that a majority of the 38 states responding to an AP survey intend to implement permanent virtual programs, partly to stem the tide of homeschooling and transfers to private schools that have swelled during the pandemic.

Many disabled students and their parents who prefer remote learning said that they do so because, among other reasons, it better protects those students’ health, reduces their risk of being bullied and their social anxiety.

Mason Winchell, a senior at the University of Washington, takes two immunosuppressant medications daily to prevent his body from rejecting organs he received in a transplant. He survived a bout of COVID-19, has been fully vaccinated and taken the booster shot. But the prescribed medicine that he takes regularly prevents his body from creating the antibodies that fight COVID-19.

His anxiety about returning to campus lasted the whole summer, until he finally was able to arrange to learn remotely. But, he told Disabled Youth Today, he “had to jump through a lot of hoops to get that remote experience set up, which was unfortunate. It wasn’t fully ready until 11:30 p.m. the day before school started.”

Even before COVID-19, disabled students were at higher risks for disease

“As a whole, students with disabilities are more vulnerable to illnesses,” said Lehigh University’s Esther Lindström, a special education professor and researcher.

As an example, 16.1% of children with developmental disorders have asthma and at least 23% have obesity. Should they contract COVID-19, those kinds of youth would be at a higher risk of COVID-related complications.

Lindström also noted that remote learning may be a buffer against bullying. A study published in 2015 in School Psychology Review concluded that students with disabilities were more than 33% likelier to be bullied than other students. Bullying, according to a 2015 study published in the British Medical Journal’s Archives of Diseases in Childhood, can interfere with academic performance and lead to depression and anxiety. Remote learning reduces those risks, Lindström said.

A February 2021 study that has not yet been peer-reviewed found that 8.4% of 606 parents surveyed in Australia and the United States reported that their children experienced a drop in anxiety and stress once they stopped going into the classroom during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to an August 2021 analysis in Oxford Academic’s Sleep journal, the flexible study hours and ability to sleep a tad longer also suggests that virtual learning may improve some disabled students’ mental health and academic performance.

Nevertheless, not every parent of a student with disabilities believes remote learning is the best option.

A child’s social and emotional development takes place in, among other places, school, said Moore, the New York teacher and mom of three. “They’re getting more input than just from the parents,” she told Disabled Youth Today.

Wilfred Van Gorp, a neuropsychologist who works with students with disabilities such as dyslexia and autism, told Disabled Youth Today via email that “learning by Zoom often ‘robbed’ students of much valued in-person social interaction, and the benefits accrued from that in terms of social development.”

Moreover, a number of school districts have seen a disproportionate increase in failing grades among students with disabilities. For example, a report by the U.S. Office for Civil Rights described a Virginia school district that suffered a 111% spike in the number of students with disabilities failing two or more classes in the 2020-21 school year.

Echoing teacher Moore’s concern about her own children, Lehigh University’s Lindström noted that students with disabilities may fall behind because many of them are not receiving the support and services to which they are legally entitled. Those include speech therapy, behavioral support, occupational therapy and one-on-one classroom aides.

In addition, many students with disabilities have trouble focusing and staying on-task while learning virtually, according to Van Gorp and Lindström.

Van Gorp said in-person learning is preferable for most students, and that students for whom remote learning is the better option are the exception and not the rule. But those students do exist and for that reason, he says that parents should be able to decide their child’s learning format alongside their child’s doctor, teachers, mental health professionals and school officials.

Even though remote instruction requires lots of planning to do well, Lindström said she agrees that the best approach “is one that centers each student’s individual needs … and provides a safe, engaging and enriching instructional experience.”