Courtesy of Laura Kopec

Laura Kopec

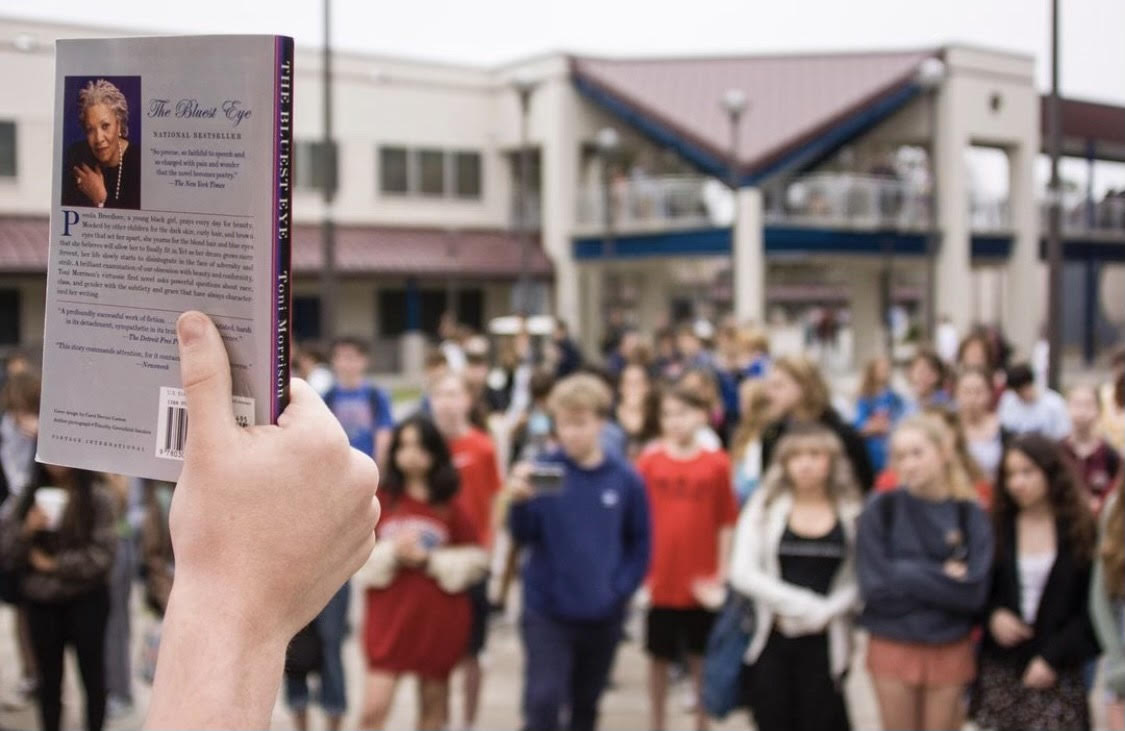

During their lunch period one February day, Laura Kopec and some classmates walked out to protest their school district’s censorship of a complicated novel that the senior read in class and found “very beautiful.”

One parent’s complaint about Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” caused Pinellas County Schools to remove the book from the shelves of its high schools this year.

A few days after the protest, Kopec and other students brought their message directly to the school board members during a Feb. 14 meeting that drew a standing-room only crowd. They held signs that said: “Save the books.”

“When the decisions were being made, no one was considering our point of view,” said Kopec, 17. “We just wanted to make sure that our truth is being told.”

The recent dispute at Pinellas County Schools comes as an unprecedented number of books are being challenged or taken off the shelves.

“We are living in a very disturbing time,” said American Library Association president Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada. “This is the highest number of book bans that we have tracked since we started tracking them 20 years ago.”

Data released last month by the ALA and PEN America detail the growing fight over what can be read in schools and public libraries.

ALA documented 1,269 attempts to ban books at school and public libraries in 2022, nearly double the number of attempts in 2021.

Courtesy of Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada

Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada

The organization reported 32% of those attempts included multiple titles.

Pelayo-Lozada said some of these challenges were part of organized campaigns by groups that contested over 100 titles at once versus previous years when libraries might have received a complaint about a single book. She described the book challengers driving this new effort as a “very vocal minority;” a recent ALA survey found 71% of voters are against book bans.

Meanwhile, PEN reported 1,477 books banned at school districts during the first half of the 2022-23 school year.

The two organizations acknowledge that this figure is likely an undercount because some schools quietly pull books from shelves.

Deciding which books young people can read has become an emotionally-charged, galvanizing battle that has led to social media smear campaigns, death threats and legislative pushes to defund public libraries.

Moms fighting back

Book censorship is nothing new in American history, according to University of Pennsylvania education history professor Jonathan Zimmerman, who points to the 1920s, when Americans fought over textbooks that taught evolution, and to the height of the Cold War, when Sen. Joseph McCarthy attacked books that were deemed un-American.

But this modern push is different, Zimmerman said.

Today’s book banning has evolved from a mostly local issue affecting a school or a community into a national issue, he said. Zimmerman said that’s thanks to social media making local cases go viral — and politicians, such as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, whose culture wars are part of a national platform.

Courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania

Jonathan Zimmerman

Leading the charge to contest book titles has been Moms for Liberty, a national group with local chapters whose members often run for local school board offices or file challenges over books.

“I do think that the volume is unprecedented because groups like Moms for Liberty have managed to nationalize the question in ways it hasn’t been before,” said Zimmerman.

Moms for Liberty co-founder Tiffany Justice argues parents should closely examine the materials in their children’s public school libraries. Her organization, in her eyes, is fighting to keep pornography away from children in school.

“Parents should never be vilified for asking questions about their children’s education,” Justice said. “It’s very clear what needs to be taught in public schools. We have standards. There’s no academic freedom in public school. You don’t get to talk about anything you want.”

Justice, a former school board member in Florida’s Indian River Country, said her organization has not put out a national book banning list but does encourage parents to “dig in” for themselves to review which books are in their children’s schools. Her organization — 115,000 members in 45 states and funded entirely by donations and merchandise sales, she said — is pushing to put processes in place to train librarians on what materials are appropriate for school libraries.

[Related: Why is a book about love the latest casualty in the book ban culture wars?]

At schools, kids can only watch movies with certain ratings and don’t get unfiltered access to the Internet, ”[s]o why would books be any different?” Justice asked.

Library advocates argue it isn’t fair for a minority of parents to deny access to books for everyone.

Silencing voices

Texas, Florida, Missouri, Utah, and South Carolina are the states with the most book bans happening, according to PEN.

Meanwhile, state legislatures are passing laws to give parents more control over scrutinizing what goes in libraries.

Other laws go further.

In 2022 Missouri passed a law authorizing criminal prosecution of librarians and educators who provide materials deemed sexually explicit to students. That year, 11 other states attempted to pass similar obscenity law changes but ultimately failed, according to ALA.

All this comes at a time when state lawmakers in states like in Florida are pushing policies prohibiting young people from learning about sexual orientation and gender identity in public schools and critical race theory at public universities.

In this political climate, many of the books being banned are written by Black and LGBTQ+ authors or tell stories featuring diverse characters, said Kasey Meehan, PEN’s Freedom to Read Program Director.

The most controversial book of 2022 was “Gender Queer,” according to both the ALA and PEN reports.

In that graphic novel, author Maia Kobabe writes a coming-of-age story that deals with gender identity and sexuality.

Graphic novels in particular are often contentious because library advocates say a scene depicting sexuality or violence is presented on its own as explicit or pornographic without being presented in the full context of the story.

“That visual element makes graphic novels a target of book bans,” Meehan said.

“The Bluest Eye,” the book at the center of the fight in Pinellas County, Florida, appears on both ALA and PEN’s lists.

Courtesy of Laura Kopec

Students rallying in support of the book “The Bluest Eye” at a Pinellas County Schools’ meeting.

The book was written by Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison and tells the story a Black character growing up at the end of the Great Depression and covers themes such as rape and racism. It left a big impression on Kopec who read it her junior year in the International Baccalaureate program.

“I felt like that was something that was really beautiful because you were hearing about different perspectives, and the point of the novel was to put a Black girl at the center of the story and see how she lived,” said Kopec, who is white.

The book opened up a dialogue on sexual assault for the students.

“I think it just taught us that we shouldn’t be ashamed of anything that we’ve experienced,” the Pinellas County senior said.

Parents gave permission for students to read the book and students were offered alternative assignments if they felt uncomfortable reading it. At the start of each chapter, warnings alerted students about sexual content and violent themes.

When the book was banned across the district in January, students came together to speak up about why the book belonged in school and to stand up for their teacher who taught it, Kopec said.

Three months later, in late April, the school district reinstated the book, according to the Tampa Bay Times. The district did not respond to a request for comment or questions from Youth Today.

“I was happy and relieved that other students will have the opportunity to learn from and benefit from the lessons in this story,” Kopec said. “But there is still so much work to be done toward preventing censorship in our state.”

Under attack

Louisiana school librarian Amanda Jones’ hair began to fall out in chunks and she lost 60 lbs. She bought pepper spray, a Taser, and often carries a gun when she travels. She began to see a therapist.

Jones, a nationally recognized librarian, says that is the toll that speaking out against book banning has taken on her — she also was doxxed online and received an email death threat last year.

Courtesy of Amanda Jones

Amanda Jones

death threats.

The ALA report says librarians feel under pressure and attack — by lawmakers looking to defund libraries and by others issuing threats against them.

“I never had any kind of anxiety in my life. All of a sudden, I was having panic attacks at work. I was scared,” said Jones, who decided to go on medical leave this semester to take a break from her job as a middle school librarian.

The backlash began last year after Jones attended a public meeting at her local public library in Livingston Parish to argue against book censorship .

Jones said she was targeted by conservatives who ran Facebook groups and launched social media attacks that called her a “groomer” and a “pedophile” and worse.

Jones finally decided to fight back.

“I refuse to be silent,” Jones said. “They’re not going to get the best of me.”

She sued the two Louisiana men she said were harassing her online for defamation last year. Ultimately, a judge dismissed her lawsuit after the men argued their comments were meant to be opinion, not fact.

Jones, who has raised nearly $130,000 on a GoFundMe account to cover her legal expenses, has filed an appeal.

For 22 years Jones has worked in the same middle school library, where her favorite part of her job is helping students find their “home run books”: stories young people instantly click with — just as Jones did with Beverly Cleary books in her youth.

Now, Jones embraces the new role she is playing in her career as she prepares to lobby her state government and advocate against bills targeting libraries.

***

Gabrielle Russon is an Orlando-based journalist who covers education, tourism and business.