Climate change is a galvanizing force for young people whose lives are being radically altered by storms, wildfires, drought, heat waves and other effects of manmade global warming.

In this ongoing series, Youth Today explores how a generation is adapting to these dramatic shifts while fighting for their future.

For youth activists, historic climate law is only the beginning

When Nnennaya Ihejirikah, an 18-year-old climate activist from Texas stood before the Capitol Reflecting Pool with the White House behind her and a microphone in front of her, she knew the window for enacting major climate legislation was closing.

As she addressed dozens of people that day in June, including members of Congress, she called for billions in climate investment to prevent the very worst outcomes of an intensifying crisis that will define her generation. President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better bill had been declared dead months ago.

“Everyone realized that if the Build Back Better or a climate bill doesn’t get passed, we are in a really bad place,” recalled Ihejirikah, a youth fellow with Our Climate, a nonprofit that engages young people to advocate for climate justice policies.

“We had to put all our eggs in one basket,” she said. “So that’s why we all kind of centralized towards this one issue.”

A megadrought has changed the way farmers look at the future of farming.

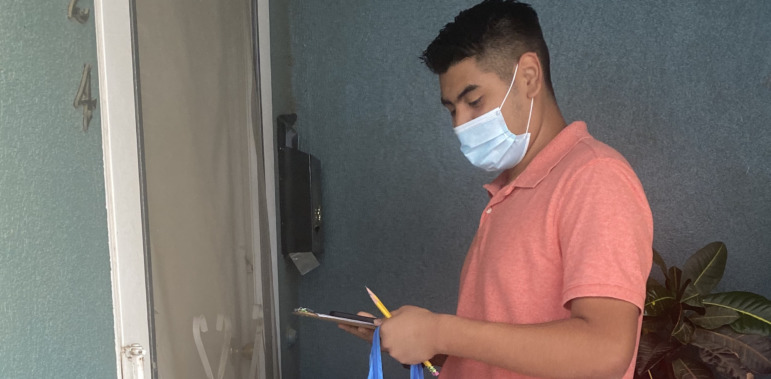

Across the country, young people are banding together to undertake surveys and create heat maps that capture their communities’ desire to mitigate and adapt to rising temperatures, which is helping to ensure that interventions are community-led rather than implemented top-down.

Student groups argue that damage to the environment and human health inflicted by the fossil fuel industry conflicts with the schools’ missions to care for their students and future generations. The groups are working with lawyers at the Climate Defense Project to bring legal complaints against their schools’ respective investment funds.

Children as young as 12 can be hired on large farms for jobs like picking tobacco, with no limits on the hours they work outside of the school day, and minimal safety protections. It’s also legal for children of any age to work with the consent of their parents on small farms. But the current law’s ambiguity and weak protections are difficult to enforce, and children younger than 12 are commonly found working throughout the agricultural industry.

The solar academy run by Chicago’s branch of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, IBEW Local 134, is a direct path to a well-paying and secure job. After five years of earning about $20 an hour, with raises every six months, students are qualified to work in a career in which they could earn up to $50 an hour plus substantial benefits and a comfortable retirement as a union electrician.

The number of “clean energy jobs” is expected to increase in the coming years as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act’s $369 billion investment in energy security and climate change. Shaun Dougherty, an expert in career and technical education, answers five questions about clean energy jobs, their expected growth and what kind of education a person needs to get one.

Seven months after Nadya Rexach-Rivera celebrated her quinceañera in her beloved Puerto Rico, Hurricane Maria upended her life. The catastrophic storm in 2017 left the island without water, power and any semblance of normalcy. She and her family survived and now, five years later in Florida, Rexach-Rivera is doing her part to help others weather hurricanes. And she is doing it with a passion to save the planet.

Six million of children in the U.S. have been diagnosed with asthma, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And more than 40% of Americans live in places with unhealthy air, according to the American Lung Association’s 2022 State of the Air report, in locales where air pollution, which fuels hurricane-causing climate change, has been linked to an increased risk of heart and lung disease, stroke, cancer and frequently flaring asthma.

Many teachers have little or no formal training about climate change, much less about how to teach it, and what students learn about climate change can vary widely from state to state and even classroom to classroom. While some students participate in carefully planned, in-depth lessons on climate change’s causes and possible solutions, many hear little about it in school.

After experiencing global warming’s firsthand effects, U.S. Latinos are leading the way in activism around climate change, often drawing on traditions from their ancestral homelands. “There has been a real national uprising in Latino activism in environmentalism in recent years,” said Juan Roberto Madrid, an environmental science and public health specialist based in Colorado for the national nonprofit GreenLatinos. “Climate change may be impacting everyone, but it is impacting Latinos more.”

La Mancha Wetland Park in Las Cruces, New Mexico, is a cool oasis in the spring heat of the surrounding desert for the beavers, turtles and birds that frolic in its waters and willow trees. The park, which is connected to the Rio Grande, is also a refuge for the young people who have dedicated themselves to restoring and managing an ecosystem under threat from climate change.

Deadly with extreme weather now, climate change is about to get so much worse. It is likely going to make the world sicker, hungrier, poorer, gloomier and way more dangerous in the next 18 years with an “unavoidable” increase in risks, a new United Nations science report says. And after that watch out.

![]()