School districts spent billions of COVID-19 relief dollars running summer programming to help students catch up from the pandemic’s far-reaching effects, but those programs did little to get kids back on track academically, according to a recent national study.

With many kids experiencing mental health and behavior issues post-pandemic, many programs focused on social emotional learning rather than academics.

“That wasn’t necessarily wrong,” Allison Crean Davis, vice president for education studies at Westat and co-author of a Wallace Foundation and Westat report on summer learning, said about states’ larger focus on social and emotional learning. “At the same time, it was equally important to emphasize academics but they are not necessarily mutually exclusive.”

[Related Story: Summer camps are booming, fueled by largest single federal funding windfall]

On average, public school students in grades three to eight, according to the Education Recovery Scorecard, lost half a year in math and three months’ worth of reading proficiency from 2019 to 2022. In some schools, students fell behind by over a year and a half in math.

Under the American Rescue Plan’s Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, known as ESSER, 70% of districts implemented new or expanded summer programming because of the pandemic; by September 2024, when the funding sunsets, combined summer and afterschool spending is estimated to reach $5.8 billion.

But in a study examining a sampling of summer schools in 2022, the Center for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) at the American Institutes for Research estimated the average summer program managed to recover just 2-3% of the overall deficit in math loss from the pandemic. The study found summer learning programs had no impact on reading proficiency.

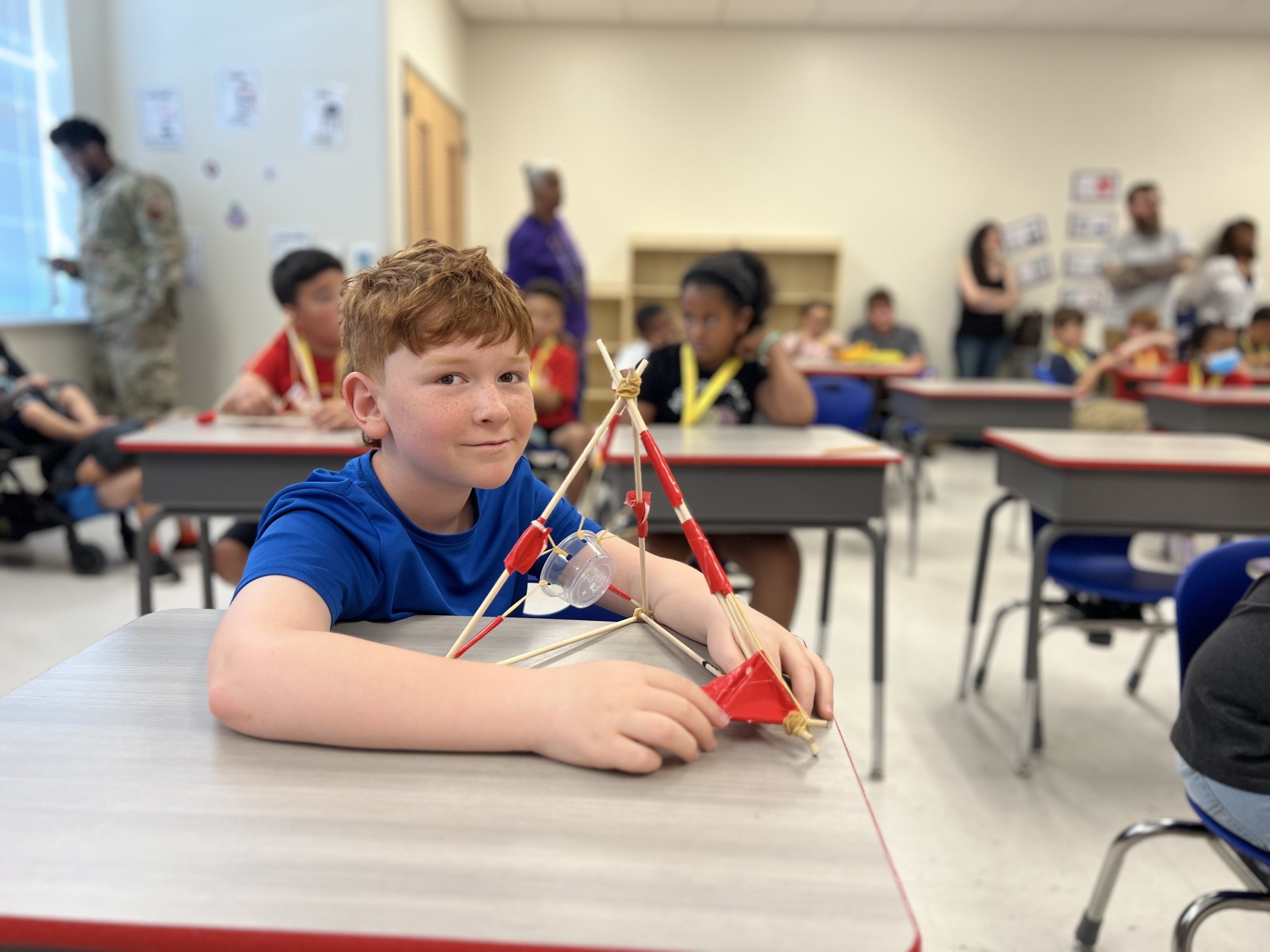

Courtesy of Richard Lewis, North Carolina Department of Public Instruction

A teacher works with students at the Wilson County Schools Summer Bridge Program in North Carolina.

According to the study authors, for summer school to get students back to pre-COVID math levels, “an average district would need to send every student to a five-week summer school with two hours of math instruction for at least two to three years in a row.”

If a school district’s goal was to use summer school to address learning loss caused by the pandemic, and for most it was, “it didn’t really make the dent that they wanted it to,” said Emily Morton, a researcher at the American Institutes for Research and one of the lead researchers on the summer school study released in August 2023.

Though the results were disappointing, Morton said it was not all bad news.

“Schools moved the needle with a significant impact on math — it was less than what we’d want it to be and it’s less than what the kids needed,” Morton said. “But this is the first good news we’ve had about recovery since the pandemic.”

Morton suggested school districts supplement summer programs during the school year with tutoring, doubling up on math classes and extending the school day and school year.

Next summer, Morton and her colleagues intend to investigate if the benefits of summer school justify the resources invested in it

Rachel Wright-Junio, director of the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s Office of Learning Recovery and Acceleration, said Morton’s report wasn’t surprising because the quality of summer schools can vary greatly from state to state, school district to school district.

“A lot of summer programs are not being implemented with fidelity,” she said.

For summer programs to really help kids they should last all day, occur five times a week and run for at least five weeks, Wright-Junio said. But some school districts might not have the money or enough teachers or staff to run a summer program to adhere to the standards.

Social emotional learning

According to a report by the Wallace Foundation and Westat, 78% of states that received ESSER funds included social-emotional elements in their programming while 41% specified academics.

Courtesy of Westat

Allison Crean Davis

Crean Davis added that even with the emphasis on social and emotional learning, the majority of districts included an academic component in their summer programs in 2022.

“Both of these are evidence-based elements that should be integrated into all summer learning programs,” Crean Davis said.

The ideal summer program would focus both on academics and helping kids recover from the emotional and social impacts of the pandemic.

North Carolina spent about $100 million on summer learning programs, requiring all grantees to provide an evidence base for their programs and interventions. The state hired the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina to study the programs’ long term impacts.

In 2022, the state’s academic performance, across all school districts, declined compared to pre-pandemic levels but is in line with the national average. According to Wright-Junio, when it comes to summer learning, the most promising results were observed in non-academic areas.

A qualitative study of North Carolina summer program outcomes found that the majority of students who participated reported that they felt safer at school and more prepared for the school year, Wright-Junio said.

“I would imagine that we would see some better academic outcomes from those students a couple of years down the road,” Wright-Junio said.

Summer schools

Courtesy of American Institutes for Research

Emily Morton

Crean Davis, vice president for education studies at Westat, said she understands why some people may be disappointed that summer didn’t live up to the promises some school districts and politicians had hoped for, but in her view, summer was never intended to be the solution the pandemic learning loss, it was meant to be the first step.

“Summer is one of the many tools in the toolkit for recovering learning loss from the pandemic, and I don’t think it was meant to be the only one,” Crean Davis said.

The emphasis on summer programming as a solution to pandemic learning loss may have been fueled, in part, by timing. The American Rescue Plan, which included the ESSER funds, was enacted in the spring of 2021, a time when many school districts nationwide were beginning to reopen.

“It made a lot of sense for summer to be incentivized as an important potential first step for some districts and states to really start to address the learning loss and the social and emotional losses,” Crean Davis said.

Students’ greatest needs

Nancy Leach, program director of the 21st Century Community Learning Center at Hyde County Schools in North Carolina, is not worried about the learning loss.

Leach said that students’ most significant needs revolve around understanding and managing their emotions and building essential social skills.

[Related Report: A national call to action for summer learning: How did states respond?]

“Students are not able to learn in the classroom if their emotional needs are not met,” Leach said.

Summer school should be “engaging and educational, but not so rigid as a classroom,” Leach said, adding that academics need to be delivered in fun and exciting ways.

The Hyde County 21st Century Community Learning Center operated at two different sites and served 200 students in a six-week program, four days a week. Teachers reported that 89% of students who attended showed improved engagement and learning, Leach said.

For Leach, the sweet spot is to combine social-emotional with hands-on learning about science, technology and math as well as reading

For example, a student from the North Carolina School of Science and Math performed an experiment at the summer program where he tied two strings on a bucket filled with water and swung it around, showing the students that water would stay in the bucket with centrifugal force.

The students enjoyed the experience so much that Leach remembered one of the kids saying, “I want to marry the STEM guy.”

***

Brian Rinker is a Pennsylvania-based journalist who covers public health, child welfare, digital health, startups and venture capital.