A two-story, holiday-decorated house with a line of people winding through room after seating-less room turned what should have been a fun-filled visit with Santa into something that the Rayne family of suburban Chicago suffered through.

Instead of a cheery chat about Christmas wish lists, Rohan Rayne got a few seconds and a couple of quick photos with the bearded guy. After that, the 11-year-old, who has a rare seizure disorder and problems handling crowds and noise, had to be rushed out of the house so he could find calm.

“It was a very difficult and challenging experience,” said Dr. Beena Kamath-Rayne, Rohan’s mother, a pediatrician, who was there with all three of her boys, trying to navigate that while providing Ro with space where he would not be as overwhelmed by all of the stimulation.

If the visit with Santa had been held in a place arranged according to concepts of the growing field of universal design, Rohan might not have been thrown off kilter as he waited more than an hour to spend time with Santa. Spaces adhering to universal design are built and laid out to meet the needs of people of varying ages, abilities and disabilities.

For example, it would give Rohan, who also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a spot away from where he got so agitated while waiting his turn with Santa.

Rohan Rayne with his mother, Dr. Beena Kamath-Rayne. (Courtesy of Kamath-Rayne family)

“I don’t have a problem with the actual waiting,” said Kamath-Rayne, also a Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation board member. “It’s just the way in which we could have been accommodated.”

Going beyond Americans With Disabilities Act provisions

Universal design expands upon accessibility as outlined in the Americans with Disabilities Act, the 1990 law resulting such accommodations wheelchair ramps and lifts being added to buildings and public transit buses and trains. Whereas, for example, an accessible multi-story building may have an elevator at the side of a structure, a universally designed one might start with a series of ramps at the entrance so that a person with mobility challenges doesn’t need to go hunting for an elevator.

And instead of retrofitting a building, universal design considers what each person would need for ease of use in the design phase.

Passed in 2004, the Assistive Technology Act provided federal funding that began yielding such examples of universal design as speakerphones and closed-captioning on television.

John Vick, a public health strategist and director of the Tennessee Department of Health’s Office of Primary Prevention, said that universal design views everyone’s needs for access as equally important, regardless of physical, social or other limitations. “Everything around us that people construct, whether it’s a building, a sidewalk or a park impacts our health. So, considering all users in the design can contribute to improving public health.”

Polio patient-turned-architect launched universal design

The concept of universal design was first coined in the 1960s by U.S.-born, internationally recognized architect and product designer Ronald Mace, who developed polio in the mid-1950s when he was 9 years old and used a wheelchair. After he enrolled at North Carolina State University, Mace found that his wheelchair couldn’t pass through the bathroom doors on that campus. Plus, he had to be carried up and down the school’s stairs, according to attorney Stephanie Woodward, executive director of the Disability EmpowHer Network. Previously, she was director of advocacy at the Center for Disability Rights.

When Mace, who died in 1998, became an architect, Woodward wrote on the center’s website that he focused on accessibility designs that would “be visually pleasing and usable to the greatest extent possible by everyone, regardless of age, ability, or situation.”

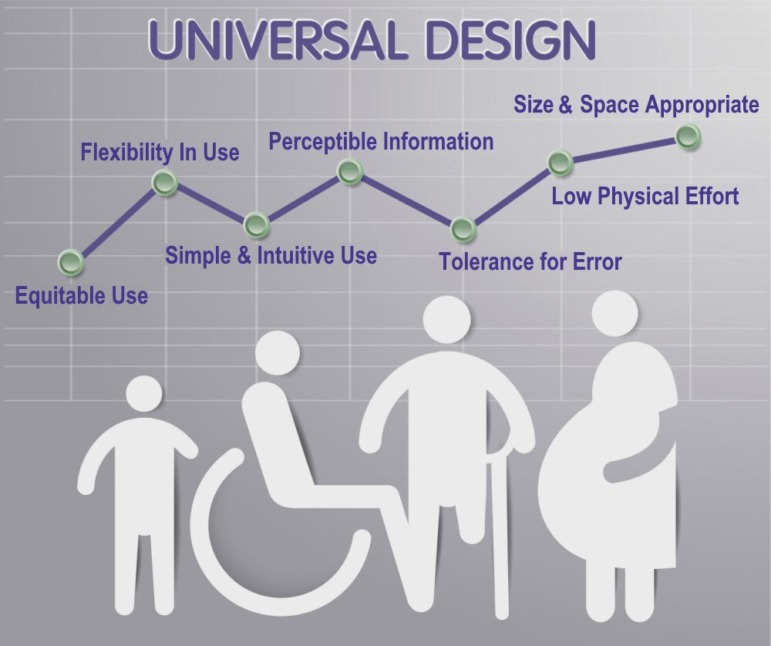

Universal design coalesces around seven principles, according to the Centre for Excellence in Universal Design in Dublin, Ireland:

- Equitable use: The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

- Perceptible information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue.

- Size and space for approach and use: Appropriate size and space are provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

vstock24/Shutterstock

The seven principles of Universal Design

Those principles are reflected in zero-step entrances to buildings; handles instead of knobs; covered bus shelters with on-demand heating; street-crossing signals that can be both heard and seen; ramps and wide sidewalks for wheelchairs and strollers; benches in public places; protected bike lanes; and directional signs and maps with large text.

“The beauty of universal design is that it considers everyone.”

John Vick,

public health strategist”

And while those and other design elements can be applied, Vick, who’s based in Nashville, stressed that universal design is far from a prescriptive approach with specific directions. Rather than having standards or required design features, it encourages creativity because multiple components and new thinking are often required to make spaces as inclusive as possible.

Although aging people have catalyzed awareness of universal design, Vick says young people benefit from it because it considers both their current and future needs.

“We’re all aging — even youth— so the approach ensures that those spaces will serve young people’s needs as they change across their lifespan,” he wrote, in an email to Youth Today. “Many young people also have physical, social, and other limitations that can be considered and addressed through the design process. The beauty of universal design is that it considers everyone.”

Universal Design inspired Universal Design in Learning

The National Center for Learning Disabilities cites universal design in architecture as the inspiration for Universal Design in Learning, which advocates for developing curriculum and assessments, or testing, of students. Some examples include incorporating assistive technology — items or software designed to enhance learning for students with disabilities — into learning and curriculum for all students, as well as providing multiple means of representation, action and engagement.

Kamath-Rayne said that Rohan works with a physical therapist at in his elementary school’s special education programs for children with disabilities. She said that students in special education often are invited to join general education students to help place them in mainstream classrooms. But her son’s elementary school has been doing the reverse by inviting general education students into her son’s special education classroom.

[Related: No more cures, no more fixes: How autistic leaders are changing the therapy debate]

Rohan’s classroom, she said, has ample space for letting kids who use wheelchairs, walkers, crutches and other mobility aids to navigate the room. Some furniture can be adapted so kids can stand while learning. There’s also a quiet space for kids who are over-stimulated and need to take sensory breaks, Kamath-Rayne said. Plus, special education teachers offer students toys to manipulate when they are fidgeting; step-by-step pictures that help guide participation in certain activities; and reward charts to help them self-regulate and become more independent.

Using universal design at the start of building projects is laudable, Kamath-Rayne said, and the broader public should also know its deeper aims.

“Everyone wants to feel like they belong somewhere,” she said. “And so what I wouldn’t want to happen is that this design philosophy became so popular, but then it was like, hidden. You know, I want people to know that we’re doing this intentionally to make people feel like they belong.”

***

Erin Chan Ding, is a Chicago-based journalist, covering fitness, health, parenting, travel, politics, race, gender. She has a special interest in the intersection of justice and journalism. Her work has appeared in several publications including the The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, National Geographic Family, The New York Times, Detroit Free Press, Forbes, Time Out Chicago magazine, The Huffington Post, Chicago Health, Los Angeles Times, and Miami Herald.