Persuading high school teens to participate in after-school programs is not an exact science, and it just gets more difficult as the youths get older. The size and reputation of a program influence the recruitment strategy, as does the available funding. Extensive recruiting efforts may be costly, or they may depend mostly on word of mouth. But they all have the same purpose: to engage as many youth as possible in order to improve their current academic standing and their whole future.

Youth Today noted the lack of national data on teen participation in after-school programs in a 2004 article (See “Attracting Teens” at http://www.youthtoday.org), and today the research base supporting effective methods of pulling in high schoolers remains thin. An April 2009 Out-of-School-Time Policy Commentary by the Forum for Youth Investment suggested that the lack of national research, along with numerous recent grant opportunities, have led to a period of experimentation. While it is too early to assess the results of these techniques, we can offer a glimpse of their recruitment methods.

One Land One People Skyline Youth Center, a fledgling program in Oakland, Calif., lacks the resources and long-term reputation of more established programs, so it relies on creativity to recruit high school students. Though the program has just four full-time staff members, its collaborative director, Tony Douangviseth, said that doesn’t mean he can’t seek out the help of others who already have active roles in the lives of high school students.

“Coaches of teams can help bring athletes to tutoring, and they can also motivate the athletes to engage in tutoring. Parents can help provide rides, academic support and food,” Douangviseth said, explaining the program’s overarching recruitment philosophy: Involve everyone.

After School Matters, an umbrella organization for hundreds of after-school programs in Chicago, claims that its reputation alone has helped recruit high school participants. While not every program has such recognition, After School Matters outreach workers employ strategies at recruitment expos that are widely applicable. In addition to setting up shop at high-traffic areas within schools, such as cafeterias during lunch period, the recruiters are sure to emphasize to students the high level of responsibility that the program places on them. This is based on the belief that students respond well when they are trusted. The expos are also an opportunity to inform students about the benefits of participation, including the increased likelihood of going to college and developing a career.

New York’s Cypress Hills Educational Choice Center takes a recruiting approach focused squarely on involving the students themselves. Lowell Herschberger, the program’s director of career and education services, said current student members help design the outreach strategy from the early planning stages all the way through to the execution. This includes having students create posters, make presentations to their classmates and hold one-on-one meetings with former students. Five years in, the results are starting to take form: The center served more than 10 times as many students last year as it did in its first year of existence.

Despite the approach, many at-risk high school students are not interested in what these programs have to offer and resist almost any effort to draw them in. That doesn’t mean after-school programs are giving up on them; the programs say they are just employing a few new and a few tried-and-true tricks – at least until research in the field catches up.

After School Matters

Chicago

(312) 742-4182

http://www.afterschoolmatters.org

|

|

What’s Cooking? Culinary arts is a popular area for those in After School Matters.

Photo: After School Matters |

The Recruitment Strategy: Get teens involved in out-of-school programs by using personal contacts, word-of-mouth, an extensive in-school presence, the support of community organizations and technology and by relying heavily on the reputation that is developed. During the interview and audition process, After School Matters instructors emphasize the program’s long-term benefits of participation – a strong entry on students’ resumes and college applications – as well as the specific skills they will learn, such as project management, punctuality and teamwork.

Getting Started: Chicago first lady Maggie Daley and Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs Commissioner Lois Weisberg founded gallery37, an arts-based summer apprenticeship program for teens in 1991. In 2000, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the apprenticeship formula for gallery37 arts programs was applied to technology, sports and communications. This array of programs became known as After School Matters, an umbrella organization for all after-school program areas.

|

|

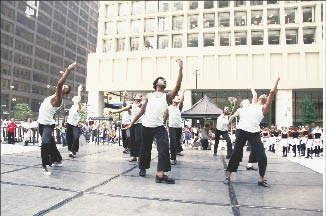

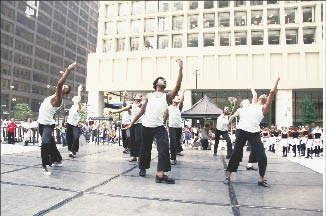

Arts are the backbone of Chicago’s after-school effort.

Photo: After School Matters |

Putting it Together: Three recruitment expos each year allow program providers to visit schools, where they make themselves available for student inquiries about program offerings. Community-based organizations also advertise at their sites and encourage neighborhood teens to enrollvia phone, mail or e-mail. A website provides teens with information about programs offered in their neighborhoods. Youth Served: With 700 programs across 57 campus sites in Chicago, After School Matters expects to serve 25,000 Chicago high schoolers in the 2009-10 school year. In 2007-08 and 2008-09, After School Matters served 27,979 and 31,067 youth participants respectively. Cuts in funding are to blame for the drop in program opportunities this year, according to the organization.

Staff: About 70 full-time employees work with a network of independent instructors and community-based organizations across Chicago. In addition, the board of directors is composed of 120 individuals who volunteer their time and resources.

Money: $23.4 million for the current fiscal year. The money comes from private contributions, public partners and government grants. Funders include Abbott Laboratories, Chicago White Sox Charities, Bank of America, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois.

Results: A 2007 issue brief from Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago found that youths with very high participation levels in the program were 2.7 times more likely to graduate from high school than nonparticipants. Those who did not participate were more than three times more likely to drop out of school than those who had very high participation levels.

Cypress Hills Educational Choice Center

Brooklyn, N.Y.

(718) 647-2800 ext. 122

http://www.cypresshills.org

The Recruitment Strategy: Use high school students to design and help carry out a program that addresses college and employment issues, in the belief that if it is something students want, they will attend. The program also uses paid internships, which require community service, to give students the power to contribute.

Some of the students, known as youth ambassadors, are responsible for creating a college-going culture at the high school by giving presentations to classmates about college and providing college counseling. The students also carry out recruitment efforts by engaging their classmates in the cafeteria, in the classroom and in individual meetings, about their prospective membership.

Lowell Herschberger, director of career and education services at the Cypress Hills Local Development Corp. (CHLDC), said recruiting for the dropout prevention program has been difficult. “We’ve found that by partnering with school administration and guidance staff, we’re better able to convince students to participate. We also find that our counseling staff’s reputation for strong counseling and interpersonal skills act as an incentive to enroll participants,” he said.

|

|

Packing Up: Center youths assemble Halloween safety packets for elementary students.

Photo: CHECC |

Getting Started: The center began in 2004 as part of a legal settlement that required the New York City Department of Education to provide funds for CHLDC to start a program that would engage students who had been pushed out of school, either because of grades or behavior. The initial mission of CHLDC when it began 20 years ago was to seek options for high school dropouts, including assisting them in the re-enrollment process. Soon, staff members learned that Lane High School was graduating less than 30 percent of its students within four years. The center’s services are now available to the school’s entire student body.

Putting It Together: The program includes several service areas:

• A Student Success Center designed to create a college-going culture on campus by providing in-class presentations about college and one-on-one college counseling. The center also provides SAT classes, college trips, and special events to promote college to the entire student body.

• Employment readiness in the form of job training and paid internships for high school students to work with local elementary school students in after-school programs.

• An attendance improvement dropout prevention service that identifies students at high risk of dropping out and provides them with weekly counseling, daily attendance tracking, family outreach and incentive trips.

Youth Served: 300 each year.

Staff: There are eight full-time staff members, several part-time staff members and 12 paid high-school interns who assist in the Student Success Center.

Money: An annual budget of $600,000; funders include the New York City Department of Youth and Development and the New York State Education Department.

Results: The number of students participating has risen from 30 the first year to 170 the following year and between 300 and 400 every year since. The number of participants who have enrolled in college has also increased each year – from one in the 2004-05 school year to 29 in 2007-08, the latest for which data are available.

One Land One People Skyline Youth Center

Oakland, Calif.

(510) 531-4387

http://www.youthtogether.net

The Recruitment Strategy: Involve anyone and everyone who can support the student – parents, teachers, coaches, etc. – to help recruit youths into the program, which is focused strictly on providing additional academic and enrichment support to Skyline High School students, which has an enrollment of roughly 2,000. In addition to working with people who already have relationships with the students, the directors have one-on-one meetings with students, explaining that to participate they must sign a one-year contract to attend the entire school year.

Getting Started: The program was started in 2005 by Jidan Koon, who was hired from outside the school and was the first youth center director, and Jamal Cooks, Skyline’s track and field coach, who now runs the youth center’s tutoring program. Cooks and Koon applied for a federal 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CLC) grant to provide after-school programming.

Putting It Together: This is OLOP’s first year in a five-year federal grant cycle. Tony Douangviseth, the collaborative director, said he works closely with coaches, teachers and the school administration to recruit new participants at the youth center, which is open all weekdays from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. However, as a result of the recession, which has hit California particularly hard, the youth center has been forced to limit its outreach to youths who can make a commitment to stay in the program for the entire school year. In past years, the center was open to all students, many of whom would move in and out of the program. Regular attendance is a requirement in order for the center to receive its grant, but Douangviseth also believes focusing outreach on a more select group of students has its benefits.

“I think it’s more effective because we are reaching each student individually, and they already know what we are expecting from their side in terms of grades, attendance and behavior,” he said.

Youth Served: The center serves 120 youths, ages 13 to 19 at the school and offsite at several partner groups’ locations in downtown Oakland. The youths are divided into far-below-basic students, below-basic students and English language-learners.

Staff: Four full-time staff members, two part-time, five subcontractors and four high school interns.

Money: Less than $200,000 annually from the school and the federal CLC program.