|

|

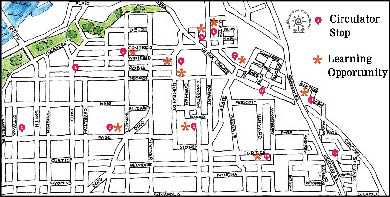

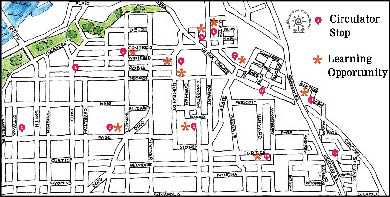

Circulating: City buses shuttle youth from pick-up points in St. Paul to youth programs, including Youth Farm, a Boys & Girls Club and the Baker Recreation Center.

|

Any restaurateur will tell you that you can have the finest food, staff and ambiance in town, but if you’re in a spot where people have trouble getting to you, you’ll be staring at empty tables. After-school program directors know the feeling.

Many an after-school program has gone all-out on high-quality programming, well-trained staff, up-to-date resources for the kids and a spiffy environment, only to wither because too many kids just can’t get there.

The transportation dilemma is especially vexing for programs in rural areas. “If we can’t pick the kids up, we often have to turn them away,” says Elva Smith, director of the Kinship program at the Indianhead Community Action Agency in Ladysmith, Wis.

It’s also a problem in cities where public transit systems are sparse, or aren’t set up to connect kids between schools and after-school programs. “Transportation is a huge issue for all youth agencies serving Rapid City,” says Mark Kline, club director at The Club for Boys in that South Dakota city.

But in Rapid City, The Club is one of several youth-serving agencies that have taken the problem by the horns, so to speak: They use buses and vans to take kids from schools to their programs.

Yes, that can be costly. But The Club says it has seen a big payoff: a 30 percent increase in attendance from the schools where it provides transportation.

Using your own buses is just one of the ways that agencies tackle the transportation issue. Other agencies align with public transportation, some combine programs to share costs, and others ask their employees use their own cars.

Crystal FitzSimons, senior policy analyst for the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), says transportation is an especially big issue for programs serving at-risk youth. FRAC recently analyzed the impact of the Child Nutrition and Women, Infants, and Children Reauthorization Act of 2004, which provides funding for transporting rural kids to food sites.

FitzSimons says transportation is the biggest barrier to getting kids to participate in the federally funded Summer Food Service Program. (See related story, page 30.) “The most successful programs are those that pick kids up and bring them to a central location,” she says. For that, agencies typically lease vans or buses.

Others, like the summer food program for the North Bend Southern District in Oregon, have purchased vans with grant funds. The Fresno County Economic Opportunity Commission in California combines its Meals on Wheels delivery with the summer food program deliveries, which allows the programs to share transportation costs.

Being in a rural area compounds the challenge. “When you talk about rural areas, you’re talking about smaller numbers of kids,” FitzSimons says. “Kids are spread out across a larger mass of land. Parents are working, and the cost of gas can also deter them from participating.”

That’s the problem for the Indianhead Community Action Agency in Wisconsin, where employees and volunteers for the Kinship after-school program provide transportation in their personal vehicles.

“If we did not provide transportation to special events, we wouldn’t have enough people to do them,” says Smith, the program director.

Even in cities such as St. Paul, Minn., transportation is a problem. “A lot of families don’t have cars,” says Marnie Wells, former initiative coordinator at the Second Shift Initiative, which serves youth during non-school hours.

Coming up with the money for vehicles, gas and insurance isn’t always the biggest challenge.

“Finding qualified drivers is a problem,” says Scott Bader, executive director of The Club for Boys. One possible reason is that the job doesn’t pay real well and covers only 15 hours a week. The Club uses two retirees and two employees to drive its vehicles.

It’s much easier to overcome these issues in big cities with good transportation networks. In New York City, for example, public school students can get free subway cards that are good for three trips a day.

Some programs get around the challenge by holding their activities in the schools, because the youths are already there. Susan Brenna, director of The After-School Corp. (TASC) in New York City, says that’s what her organization promotes.

“It’s easier for families and safer for kids not to have to travel,” she says. “But programmatic reasons take precedence over transportation. It’s easier to align the programs with what’s going on in the school if they’re held in the school.”

Kline, of The Club for Boys, believe kids need a new outlet after school, as well as a change of scene.

Bader, The Club’s executive director, says youth-serving agencies should work together more on transportation. He cites Rapid City as an example: The Club, YMCA and Girls Inc. have their own transportation systems. “I would like to see us partner with other organizations instead of everybody going their own way,” he says.

That’s what St. Paul’s Second Shift Initiative tries to do, by coordinating the operation of buses called Circulators, which offer free transportation to young people in certain city communities. The buses have designated stopping places at schools, libraries, recreation centers and youth clubs.

“What we wanted to do was plug into the after-school and summer programs and create connections,” says Wells, the former coordinator.

On the following pages are examples of how some programs are meeting the transportation challenge.

Deborah Huso is a freelance writer in Blue Grass, Va. dhuso@youthtoday.org.

The Club for Boys

Rapid City, S.D.

(605) 343-3500

http://www.theclubforboys.com

|

|

The wheels on the bus operated by The Club for Boys in Rapid City, S.D., helped increase attendance from the schools it served by 30 percent.

Photo: The Club for Boys |

Approach: The Club for Boys offers after-school activities for boys Monday through Friday. It began providing transportation to some of its members two years ago, and now provides bus service from three Rapid City schools.

The Club bought an old school bus, leases a bus from a church, and had a bus donated by the Shakopee tribe. The transportation services cost about $64,000 a year, including drivers’ salaries, insurance, fuel, repairs, and licensing, The Club says.

The local Girls Inc. and the YMCA have been providing transportation to their youth participants for several years.

History and Organization: The Club for Boys started in 1963 and focuses on after-school programs geared toward reducing juvenile delinquency.

Youth Served: On average, The Club serves 200 boys a day, ages 6 to 17. The youths come from 16 elementary schools, four middle schools, and two high schools, as well as a few private schools. Fifty-three percent of club members qualify for free or reduced lunches.

Staff: Twenty-two full-time employees, five part-timers and five part-time youth employees. Two full-timers and two part-timers provide the transportation services.

Funding: The club’s annual budget is $1.7 million.

Two of the schools served by the transportation system are considered underserved, allowing the club to use a federal 21st Century Community Learning Centers grant for some of the transportation.

The club raises 43 percent of its budget through its sales at its thrift store. The rest comes from fundraising events like art shows, a Father’s Day run and a Christmas tree sale.

Indicators of Success: Executive Director Scott Bader says that after the club began busing youths from the three schools, club attendance from those schools rose by 30 percent. “There were some other factors involved, like better staffing and more activities,” he says, “but the bulk of that increase was due to our busing.”

The Club for Boys offers activities and programming to boys before and after school, which makes things easier for working parents. “There are kids who are now coming on a daily basis who couldn’t get here before,” says Club Director Mark Kline. “Now parents can drop them off at the club before school and pick them up after work.”

Second Shift Initiative

St. Paul, Minn.

Brad.Meyer@ci.stpaul.mn.us

http://www.ci.stpaul.mn.us/index.asp?NID=340

|

|

Drummed in: Some children ride the buses to music class.

Photo: Office of the Mayor, St. Paul, Minn. |

Approach: The Second Shift Initiative is a city government effort to promote youth access to and use of recreational and educational opportunities during non-school hours. While the initiative promotes programs offered through St. Paul’s Parks and Recreation Department – including cooking, puppet-making and basketball – its transportation service takes kids to many different activity sites around the city.

Second Shift coordinates the leasing of four buses, called Circulators, which serve kids in neighborhoods on the city’s West Side and East Side, making stops at schools, libraries, youth clubs (such as the YMCA), and parks and recreation centers. Kids ride the buses for free. The buses have been running only during the summer months, but the city plans to run them after school beginning in the fall.

History and Organization: The first Circulator, born of a grassroots neighborhood effort, began on the West Side in 2004. The Second Shift Initiative got off the ground in 2005 through a summit of 300 youth workers and partnering organizations, initiated by Chris Coleman, who became mayor in 2006. That year, the Coleman administration launched Second Shift as a government program, which emulated the Circulator concept elsewhere in the city.

Youth Served: The city says the initiative provided 10,000 rides to school-age young people last summer. While Circulators are available to all children, former coordinator Marnie Wells notes that the buses run in low-income neighborhoods.

Staff: Second Shift has one employee, Coordinator Vallay Varro, who replaced Wells in April.

Funding: Second Shift has no budget of its own, although Wells hopes it will become a line item in the City of St. Paul’s budget. The coordinator’s annual salary of $70,724 is paid by the city’s Park and Recreation Department. The Circulators are funded through private foundations, including the McNeely Foundation, 3M Foundation, Travelers Foundation, Greater Twin Cities United Way and the McKnight Foundation, as well a grant from the Minnesota Department of Education.

As an example of cost, the three East Side buses cost about $75,000 a year to operate.

Indicators of Success: Wells says Second Shift has conducted no formal studies of its transportation initiative, but that given the number of rides provided last summer, the initiative is clearly helping youths get to sites and activities. She also says city librarians reported an increase in the number of youth visiting the libraries during the day last summer.

Kirkland Boys & Girls Club

Kirkland, Wash.

(425) 827-0132

http://www.onepositiveplace.org

|

|

It pays: Families can pay for transportation to the Kirkland Boys & Girls Club.

Photo: The Kirkland Boys & Girls Club |

Approach: The Kirkland Boys & Girls Club has been providing transportation since the 1990s. The club has steadily increased its transportation offerings over the years and now owns a school bus to take kids from elementary school to the club each day, along with six vans that do the same at six other elementary schools.

Children pay $30 per year to belong to the club, and can pay another $55 to $75 a month for transportation. Senior Program Director Bridget Powers says children can apply for membership and transportation for free or at reduced rates, based on family income.

Once children reach the club, which is open from 2:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. Monday through Friday, they get snacks, have a Power Hour of homework time, then select from activities that include games, gym time, computer use, art projects and pool.

History and Organization: The club began in the 1970s and was designed as a drop-in after-school program for Kirkland area youth.

Youth Served: Kirkland serves 80 to 100 kids a day, and its total membership base is 3,000. Participants range in age from 6 to 18; most are in elementary school.

The majority of the youth participating in the after-school programs arrive on the bus or the vans, and most of those are from low-income families.

Staff: Eight full-time and seven part-time employees. Some staffers drive the vans.

Funding: The annual budget is about $800,000. About $30,000 of that goes to cover costs associated with transportation. The club receives some United Way money, but most of its funding comes from program fees and fundraising efforts, such as a black-tie silent auction.

Indicators of Success: Powers says transportation has been vital to the club’s success. She notes that participation numbers have increased every time the club has offered transportation from a new school.

Kinship

Indianhead Community Action Agency

Ladysmith, Wis.

(715) 532-5594

http://www.indianheadcaa.org

|

|

Driven: Kinship’s mentors know they’ll be providing transportation for their youths.

Photo: Kinship |

Approach: Kinship provides mentoring services and access to meetings like Teen Talk, which gives kids a forum to discuss such issues as sexual abstinence, drugs and peer pressure. The youths also participate in community service projects, such as cleaning and painting parks.

Because the Kinship program is located in a rural area, it’s not easy for children to get to programs or to meet with mentors unless Kinship provides the transportation service. Kinship staffers use their own vehicles to pick up kids and to return them to home or school. Mentors know when they come on board that they’re expected to pick up youths for their weekly meetings, which include activities like camping, fishing, going to movies or helping with chores at home.

Director Elva Smith says Kinship offers reimbursement to program staff members who drive kids to and from activities, but as the cost of gas rises, it’s becoming tougher for staffers and volunteers to bear the burden. Kinship’s reimbursement rates are low – 40.5 cents per mile, and available only to paid staff. (The federal government’s reimbursement rate for privately owned vehicles used for employment, which sets the standard for many private employers, is 50.5 cents per mile.)

History and Organization: The Kinship program in Ladysmith is part of the national Kinship network started by a teen in Minnesota 50 years ago. It has nearly 50 affiliate networks across the upper Midwest. Its model is similar to that of Big Brothers Big Sisters. The Ladysmith program has been providing transportation to its participants since its beginning in 1977. Kinship came under the umbrella of the Indianhead Community Action Agency (ICAA) in 1997. Smith says one reason Kinship became part of the ICAA was to get help covering costs, particularly insurance.

Youth Served: Each year Kinship serves about 60 low-income children, ages 5 to 18, in rural northwestern Wisconsin. While the program does not have income requirements for participation, Smith notes, “Almost everybody here is at poverty level.”

Staff: The ICAA has three full-time employees and one worker each from AmeriCorps and Experience Works.

Funding: ICAA’s Kinship program has an annual budget of $70,000, with $10,000 of that funded by a Community Services Block Grant from the U.S. Administration for Children and Families. The rest of the funding comes from small grants and donations from local organizations, such as the Jaycees and Kiwanis, as well as fundraising events, like an annual bowling competition.