When Shay Bilchik thinks about the potential of involving adjudicated youth in juvenile justice reform, he recalls the impact of foster children who helped persuade Congress to pass the Chafee Independent Living Act of 1999.

The bill “wasn’t going anywhere fast, until youth became involved in testifying and promoting it,” says Bilchik, former head of the Child Welfare League of America. “Lo and behold, a multimillion-dollar bill passed.”

At a time when states are rethinking their “get tough” juvenile justice policies and Congress is set to reauthorize the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, advocates are increasing their efforts to involve adjudicated youth in justice reform. Those efforts, however, face an array of challenges.

“The youth voice is being taken much more seriously than 15 years ago,” says Bilchik, who led the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention during the Clinton administration and is now director of the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform and Systems Integration at Georgetown University in Washington. “It’s not easy for the youth themselves to mobilize. There are special considerations.”

|

|

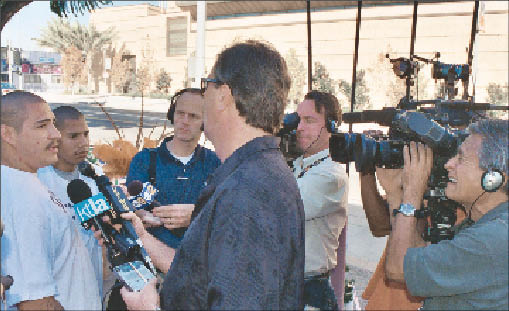

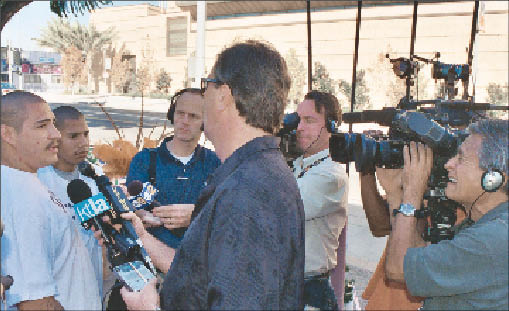

Making their voices heard: Young people with the Youth Justice Coalition hold rallies and speak to the news media to get their point across.

Photo: Photo courtesy of YJC |

“It’s a critical thing … to involve young people who are directly affected by the system you’re trying to change,” says Sarah Bryer, director of the National Juvenile Justice Network. That’s because “the things you’re demanding are informed by the people they’re directly affecting, and because young people can sometimes make the most compelling cases for why things should be changed.”

But system-involved youth often feel too beaten down or disaffected to step up, says Bryer, whose organization, along with the National Collaboration for Youth, published a policy brief on the subject in May (http://njjn.org/media/announcements/announcement_link_145.pdf). “It’s challenging to convince them to have a voice,” she says. “A lot of young people will see their individual plight as individual.” The key is to show them that “what’s happened to them is part of a larger problem.”

Foster children tend to have less compunction than adjudicated youth about speaking up because they sense less stigma about their label, says Robert Schwartz, executive director of the Philadelphia-based Juvenile Law Center. “It’s not as though kids want to announce that they’ve been in the [justice] system, or identify themselves that way,” he says.

“You’re not going to the straight-A kids in the best high schools,” Bryer says. “You’re reaching out to kids in juvenile detention centers, on the streets – kids who might not feel as authorized to do advocacy work.”

With some effort, Schwartz says, youth workers can find adjudicated youth “who are quite special [and] who are willing to speak about their past mistakes.”

Then come practical considerations, like providing transportation to meetings and rallies, scheduling gatherings at convenient times and offering small stipends.

For youth workers to effectively reach out, they need an educational process of their own, says Renee Carl, director of policy and government relations for the National Collaboration for Youth.

“Giving young people the opportunity to grow and become leaders is essential,” she says. “It’s also essential to provide professionals with the training and ongoing professional development … to engage those young people, and do it in a positive way.”

Among the strategies being pursued is online advocacy, says Thaddeus Ferber, program director of the Forum for Youth Investment and chairman of the Youth Policy Action Center (YPAC), a Web-based advocacy effort.

“There’s been an increased attention to the use of social networking sites, such as MySpace and Facebook, in engaging young people in advocacy,” Ferber says. He cites a campaign led by the Connecticut Juvenile Justice Alliance, which used a “critical” online component organized by YPAC to help pass a state bill that moves 16- and 17-year-old offenders from adult courts to the juvenile justice system. The bill was signed into law in June.

Bryer calls that campaign “a tremendous victory. They had young people testify. At one of their educate-the-Legislature days, they had all of these young people and their peers who are going to benefit from this come to the table.”

Bilchik envisions a combination of nonprofit action networks that mobilize youth around specific bills or issues, and ongoing youth representation on government bodies that have input into juvenile justice policies. “It’s important to bring youth to the legislative hearing table to have them tell their stories – not just to pull at the heartstrings, but to identify what should have been done differently,” he says.

Following are profiles of efforts to involve youth in juvenile justice reform.

Youth Justice Coalition

Los Angeles, Calif.

(323) 235-4243

The Approach: The Youth Justice Coalition has developed about 19 chapters in various parts of Los Angeles County, based at a mélange of organizations that include juvenile halls, charter schools and a YouthBuild site, says youth organizer Rodrigo “Froggy” Vasquez. The coalition has individual members and 85 organizational members.

|

|

A key to success for YJC has been helping youths hone their public speaking skills.

Photo: Photo courtesy of YJC |

During regular meetings, the youth members learn about political movements and how to promote positive change, the history of gangs, the ways in which urban youth are stereotyped in the media, and how to become comfortable speaking in public, Vasquez says.

“The whole thing is to develop their speaking abilities, so that wherever they go – the mayor’s office, city offices, the state Capitol – they’ll be able to speak comfortably,” he says. “They’ll know their issues. A lot of times they’ll know their community is screwed up, but they don’t know the political standpoint behind it. … We study the system and how it came to be.”

The coalition produces a newsletter that helps educate youth about the issues they face. One recent article explored California’s history as an educational Mecca and tracked what some see as a decline in its educational system alongside a rise in prison construction. “California used to be No. 1 in education,” Vasquez says. “Now, we’re No. 1 in building prisons and locking people up.”

Among the issues youth members have advocated is to tighten the city’s methodology for placing youth in its gang database, which Vasquez says has been “too general.” Wearing baggy clothing, having short hair and living in a certain area has been enough to get someone on the city attorney’s list, and until recently there was no way to get off the list.

History: The Youth Justice Coalition began in 2002 as a spin-off from several adult-oriented justice advocacy organizations. “They feel like the people who should address this [juvenile justice] issue should be the people directly affected,” Vasquez says.

Youth Served: The coalition has between 300 and 400 individual members, ages 7 through 24, who often join after attending a training session – such as “Know Your Rights” or “Organizing 101” – that coalition staff hold at youth-serving organizations around the county.

Staff: Two full-timers and about a dozen part-timers.

Funding: The annual budget is $150,000 to $200,000 a year, the coalition says. It has a “fiscal sponsor” – Try Again, Inc., which works with youth on probation – and support from such foundations as Funders’ Collaborative on Youth Organizing, the Hill-Snowdon Foundation and the Latino Coalition.

Indicators of Success: Among the successes cited by the group are helping to: stop the transfer of youth to a county jail, get unlimited postage stamps in California Youth Authority facilities, increase the use of “probation camps” as an alternative to CYA incarceration, and establish family resource centers at juvenile detention facilities.

Colorado State Advisory Group

|

|

Standing for youth: SAG youth member Jeremy Wilson (center) with staffer Anna Lopez and member Joe Higgins.

Photo: Photo courtesy of Colorado SAG |

Denver, Colo.

(303) 239-5717

The Approach: Like many State Advisory Groups (SAGs), the one in Colorado has persistently struggled to fulfill one requirement: recruiting youth representatives.

Created by the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974 to advise state officials, SAGs must have at least 20 percent youth representation to receive funding under the act. Among other things, SAGs make recommendations for coordinating juvenile delinquency programs and related services, such as health care and public assistance. Members are chosen by governors.

The Colorado SAG has 27 members, seven of whom are youth.

“It’s incredibly difficult” to involve youth, says Meg Williams, a SAG member who is director of the state Division of Criminal Justice. “But it’s very encouraging if you can engage them.”

SAG Chairwoman Dianne Van Voorhees says the obstacles to youth participation include transportation, finding a meeting schedule that works for a diverse group, and the fact that youth don’t always understand their roles on the SAG.

Lindi Sinton, the group’s immediate past chairwoman, says the difficulties tend to revolve around the competition for the youths’ time. The SAG meets quarterly, and “we’re asking them to take full days out of their schedule” for those meetings, she says.

Over the past couple of years, however, the Colorado SAG has had little trouble keeping itself stocked with youths. The keys have been improving support for youth members and giving them more authority, which has reduced turnover and made recruitment easier.

Each youth is now assigned a council member who serves as a “buddy” to guide him or her through the alphabet soup of acronyms and other jargon. “Some of the business stuff can be pretty dreadful,” Sinton says. “It’s not exciting.”

Carrying out that concept “takes time and attention, but it’s worth it,” Williams says.

Van Voorhees says that another helpful step in attracting and retaining youth has been the formation of a youth subcommittee that meets separately and oversees a grant-making program for local, youth-led programs. She says that subcommittee can award about $20,000 a year, with up to $5,000 for each organization.

“Giving them the responsibility [for the mini-grants] makes a huge difference,” she says. “We’re not just saying, ‘It’s nice to have you sitting there.’ They’re taking it on.”

In addition, Van Voorhees says that because many adult SAG members work with the juvenile justice system in their jobs, they can offer job-shadowing opportunities for some of the youths.

Sinton says the youth involvement “keeps us honest. … We can sit around and talk about juvenile justice until we’re blue in the face.”

History: Neither Sinton nor Van Voorhees is certain when Colorado’s SAG was established, but they believe it was within six years of the JJDPA’s passage.

Youth Served: Williams says adult advisory group members recruit youth, looking primarily for “at-risk youth, which is a hard thing to necessarily identify,” Van Voorhees says.

“We look at who comes in contact [with the system], who is over-represented. It’s going to be youth of color, including Native Americans. It’s going to be people who are not of the mainstream culture. … It’s going to be poor people.” The SAG has also distributed fliers among college students.

Van Voorhees isn’t sure how many of the youth members have had direct contact with the juvenile justice system.

Staff: Williams and two of her staffers in the state Office of Adult and Juvenile Justice Assistance focus on the SAG.

Funding: The SAG receives $30,000 annually from the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Indicators of Success: Williams says it’s difficult to quantify the SAG’s impact because “what we do is so collaborative.” For example, two years ago a legislative subcommittee on mental health joined forces with the SAG to create a task force that produced a plan and led to “a series of positive legislation” about youth mental health, she said.

Cook County Juvenile Advisory Council

Chicago, Ill.

(312) 433-4465

seiseman@cookcountygov.com

|

|

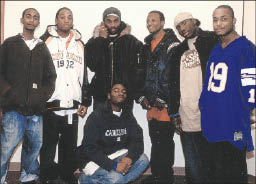

Ex-probationers now serving as JAC youth representatives (standing left to right): Demetrius Edwards, Marquel Payne, Maris White, Donald Scott, Lazarus Larkin and Dalvin Williams, with Robert Wilson (kneeling).

Photo: Photo courtesy of Juvenile Court of Cook County |

The Approach: The council provides a forum for youth to help the Cook County Probation Department assess the quality of its services. The purpose, says Steven Eiseman, deputy chief probation officer: Help to answer the question, “How well are our programs and services actually working, not just on paper but in the lives of kids?”

The council meets monthly and relies heavily on youth representatives to guide its work.

Among the programming it has developed with youth input is an orientation that it runs every other month for youth who have just entered probation. Those youth-led sessions include a skit called “Probation Scene: What’s It Mean?” A youth from the audience plays the part of a judge, reading lines from a script, while instructors stop the skit and ask questions.

“We get the kids to think about things like underage curfew, drinking, traffic laws,” Eiseman says. “When the probation officer wants you to go to a program, do you have to go? We want to get the kids to think about the meaning between the lines.”

The council also developed a system of exit interviews for youth to conduct within a month of getting off probation. They complete a survey, and then break into small groups.

“We asked the kids in the course of our exit-interview program, ‘If you had been your own probation officer, what do you think you would have done differently?’ We ask questions about programs: ‘What programs do you think made an impression on you? … What meant more to the kids than anything else were PO’s who listened to them, talked to them, let them explain their side.”

As a result, the department instituted training to steer officers toward interviewing youth rather than interrogating them, Eiseman says.

History: The Juvenile Advisory Council began at the end of 2002. Over the probation’s department’s previous 60 years, Eiseman says, “Not once … had we gone to kids and families who are the beneficiaries of everything we do and asked them, straight out, ‘What good came from probation? What message got through? What happened that made a positive difference in your life? What made no difference?’

“We had to start walking the walk, rather than just talking amongst ourselves.”

The department invited its youth “clients” to participate in focus groups, luring them with $20 stipends, bus cards and free refreshments. Among the findings, Eiseman says: Only about one-quarter of youth had a solid understanding what probation was supposed to accomplish, one-third were “hazy about certain aspects,” and the rest had “very little intellectual grasp of the reasons or rationale. This disturbed us.”

One youth commented: “Wouldn’t it be great if everybody got information the same way? What about an orientation to probation, to make sure everybody’s learning and hearing what they need to know?”

Eiseman recalls, “We thought, ‘What a great idea.’ ”

Youth Served: The council has about 15 youth representatives in Chicago, and a few at a satellite court location in suburban Rolling Meadows. About 2,000 have participated in the orientation and exit interview program, Eiseman says.

Staff: Led by Eiseman, the council gets volunteer help from six to eight department staffers at any given time. “I could use more staff involvement,” he says. “It’s asking people a lot to give up time like that for something they are not required to do.”

Funding: The council receives about $10,000 annually from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Indicators of Success: Less than 20 percent of those who attended the council’s orientation have violated probation during the first six months, compared with 46 percent who didn’t attend.

Youth representatives have led workshops and done presentations for groups of professionals from across the country.

Each One Teach One

New York, N.Y.

(212) 254-5700, ext. 312

|

|

Teaching: Youth organizer Thomas Mims (left) with program participant Fausto Perez.

Photo: Photo courtesy of Each One Teach One |

The Approach: Part of the Correctional Association of New York’s Juvenile Justice Project, the Each One Teach One program trains 13- to 19-year-olds in leadership and organizing skills. Instruction is provided by older youth and young adults who have been in the juvenile justice system.

The content covers such subjects as knowing your rights, the black power and women’s movements, and how the city budget works, says youth training coordinator Asadullah Muhammad. Workshops titles include “Some of My Best Friends Are: The Issues Facing LGBT Youth,” “Getting Your Message Across: Using Media as a Tool,” and “The Front Line: What is Community Organizing?”

The workshops go beyond activism to overall youth development, including college preparation, healthy eating, personal development and “recreating your self-image,” Muhammad says.

He says half the participants have been incarcerated, all are from underserved communities, and those who haven’t been in jail know people who have been. “What we talk about hits very close to home for all the young people. They all want to stop the rail to jail.”

The program culminates in juvenile justice-related “Advocacy Days” in Albany, the state capital. Muhammad says those events, which the association has held for years, “have become even stronger because young people are being trained by other young people.”

Participants have created a public service announcement about the school-to-prison pipeline and put on dramatic productions based on their experiences in the juvenile justice system.

History: The program started in the summer of 2004 to help ramp up the Advocacy Days, Muhammad says. The youths “were helping to push bills forward. Having that face-to-face contact made a difference,” he says.

The program began with 10 four-week cycles, but organizers realized the courses needed to be longer. They now run during three semesters each year: spring, summer and fall.

Youth Served: Staffers interview about 40 youth and choose about 15 each semester. They find candidates through high schools, community programs, alternatives-to-incarceration programs and word of mouth.

Staff: Muhammad and two youth interns chosen from the previous semester, plus an intern from the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services.

Funding: The annual budget for Each One Teach One is $420,000. The major funders are the Public Welfare Foundation, the New York Foundation, the New York Community Trust and the Open Society Institute.

The youths receive a $50 stipend every two weeks.

Indicators of Success: “Advocacy is an extremely long process. We can’t say ‘Each One Teach One’ has helped this bill get passed,” Muhammad says.

The youths recently pushed for the Safe and Equal Treatment of Youth Act, which would establish a nondiscrimination policy in state facilities.

“We’ve had our young people work with the ACLU in their report about young girls’ incarceration,” Muhammad says. “We’ve had people – researchers and writers – constantly reach out to our young people to help in having a story that can be linked to a bill.”