The facts in Brian Rinker’s recent Youth Today story Pandemic pushes afterschool programs to add social-emotional learning rang true. Out-of-school time program staff are seeing an uptick in behavioral challenges that require staff to have more specific tools, practices and referral options. He writes:

“Over the past decade, schools have been working to teach students how to better regulate their emotions and have positive interactions with others, in lessons often called social-emotional learning. But those lessons rarely spread to summer and afterschool programs that play major roles in children’s lives – until now.”

This statement is true. Out-of-school time programs, until the pandemic, did not see a pressing need to integrate formal social-emotional teaching into their program activities. This is not, however, because they don’t value the importance of social and emotional skill building. Quite the opposite.

The lack of demand for formal curricula designed to teach skills is related to the abundant supply of integrated opportunities to practice them.

The lack of demand for formal curricula designed to teach skills is related to the abundant supply of integrated opportunities to practice them.

In Social and Emotional Learning in Out-of-School Time, Dale Blythe talks about social-emotional skills being both caught and taught. Out-of-school time programs have traditionally emphasized the caught, building these skills through opportunities for modeling and practice.

To understand how the current moment calls for more explicit, taught instruction in the out-of-school time space to complement this historically integrated skill building, we must explore the connection between behaviors and settings.

In any given moment, behavior is the combination of capacity, opportunity and motivation. This research-based observation is known as the COM-B model. Unlike schools, afterschool and summer programs are voluntary and offer more flexible activities and student and staff groupings. Other things being equal, the broader array of interest-driven opportunities means that students with the same capacity to manage their behavior and strengthen their skills will be more motivated to do so than when in school.

The stress and isolation associated with the pandemic reduced all our capacity to manage our behavior. This is why, as Brian Rinker notes, it is important to take extra care to attend to the social, emotional and mental health needs of youth and staff. Kids and adults who were managing fine pre-pandemic may need more targeted social and emotional coping strategies and mental health supports. (It is critical to remember social emotional learning and mental health are related but distinct disciplines.)

This has resulted in out-of-school time programs adding more explicit or “taught” instruction in social, emotional and cognitive skills, schools adding more embedded or “caught” social-emotional learning and greater alignment of how both settings teach the topic.

Both schools and out-of-school time programs can agree on the goals associated with a “whole child” approach. But how they work towards these goals will be different, making alignment challenging. Understanding the challenges requires looking at the commonalities and differences in the primary contexts associated with school and out-of-school time programs.

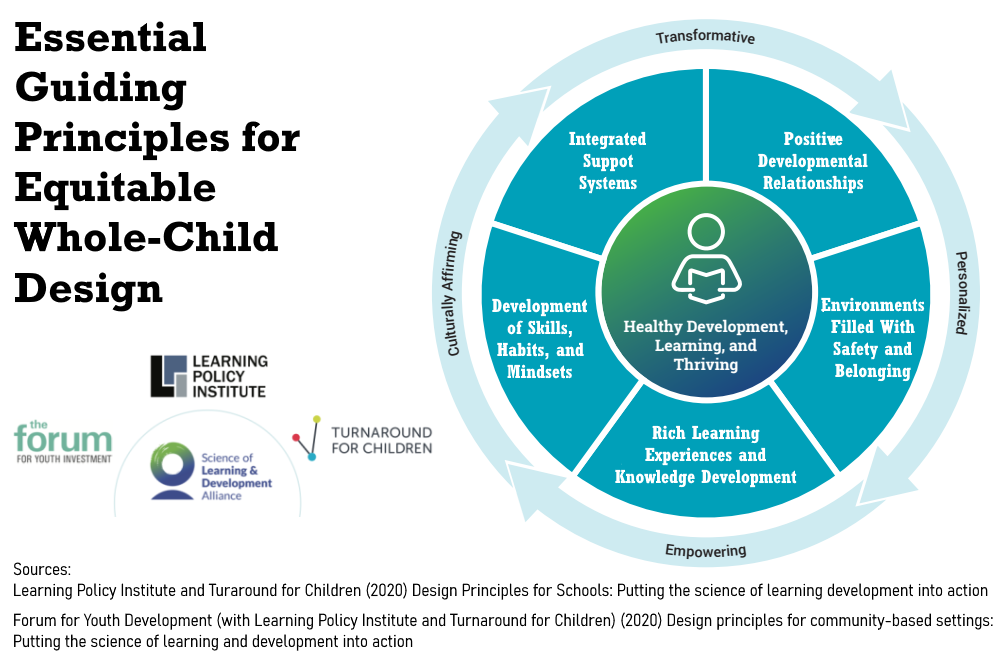

The starting points, as identified in the SoLD Alliance playbooks on the Essential Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole-Child Design for both K-12 and community settings, vary both between and within school and community settings.

Schools emphasize knowledge development. Community programs tend to start with relationships and belonging. But there are settings within schools where relationships are emphasized, such as extracurricular activities, and community settings where knowledge is emphasized, such as science museums.

The pandemic disrupted all of the places where learning and development happen — in families, schools, community organizations and across the broader community. Out-of-school time programs responded by putting more emphasis on “taught” supports. But many schools responded by making more time and space for sharing activities where skills can be modeled and “caught” — morning welcomes, sharing circles, advisories. This balance between explicit and embedded teaching works for social, emotional and cognitive skill building and academic subject mastery.

This is a time for both schools and community programs to learn from each other: As noted in Design Principles for Community-based Settings, “One setting or organization’s weakness could well be another organization’s strength.”

***

Karen Pittman is a partner at KP Catalysts and the founder and former CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment.