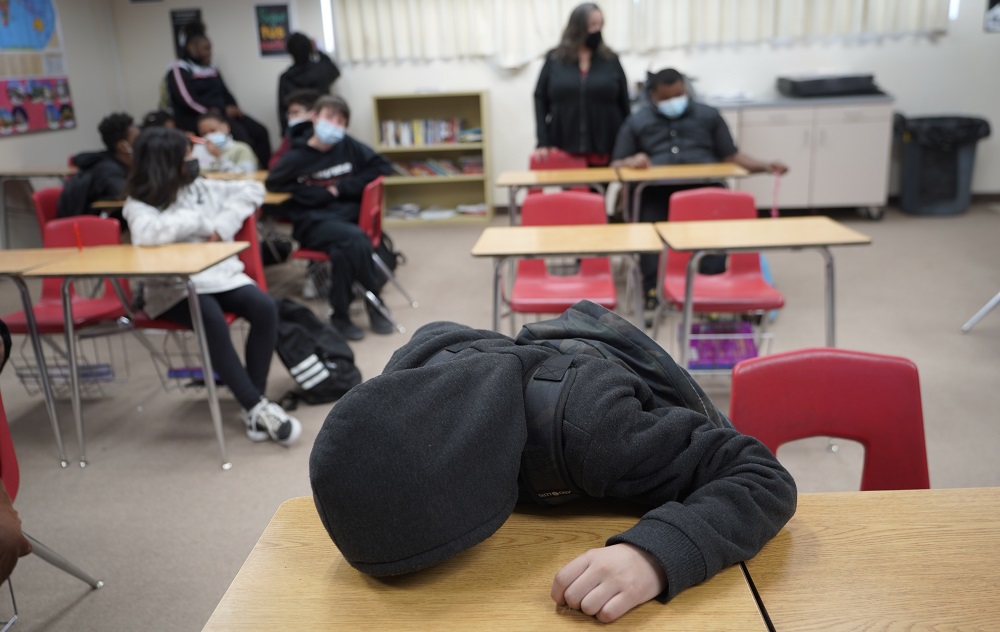

Damian Dovarganes/AP

An unidentified student rests on his desk at California City Middle School in California City, Calif., on Friday, March 11, 2022. California is one of several states that have passed laws allowing students to take excused sick days for mental or behavioral health.

Like many other teens, Caroline Edgeworth felt her anxiety surge when the pandemic started. The Las Vegas student was confronting the usual challenges of junior year in addition to navigating a massive public health crisis. She said that sometimes, she needed a day off.

“There was no particular reason,” said Edgeworth, now 18. “I just felt really overwhelmed and anxious. I couldn’t feel myself going to school that day.”

Edgeworth didn’t just take the occasional mental health day for herself. Instead, she and her sister, Lauren Edgeworth, lobbied their legislators to give other students the same option.

Last June, Nevada became one of 13 states that have passed legislation allowing students to take an excused absence from school for mental or behavioral health reasons. Similar legislation has been introduced in at least seven others.

The language varies from state to state, with some bills limiting the number of allowable mental health days and others requiring a mental health professional to certify the absence. But the concept is the same: to add mental and behavioral health to the list of reasons that school districts can or must excuse a student’s absence. In doing so, lawmakers say they aim to destigmatize mental illness and support student wellbeing, often in response to urging from students themselves.

According to Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, school districts have historically taken a “punitive” approach to attendance — one which recent research has shown is ineffective. Some districts treat truancy as a crime, and some automatically withdraw credit if a student misses more than three days, forcing them to retake classes.

According to Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, school districts have historically taken a “punitive” approach to attendance — one which recent research has shown is ineffective. Some districts treat truancy as a crime, and some automatically withdraw credit if a student misses more than three days, forcing them to retake classes.

Mental health day policies help shift the framework, Chang said, from asking students “What’s wrong with you?” to asking “How can I help?”

For some students and legislators, these measures serve as recognition that emotional wellbeing, like physical wellbeing, can vary on a day-to-day basis.

“You don’t necessarily have to have a specific diagnosis, but you can wake up and feel like, ‘I just can’t face the day today; I need a break,’” said Pennsylvania State Senator Judith Schwank, who sponsored a pending bill to give students two mental health days per year.

“Part of building your mental wellness is acknowledging that you don’t feel so great, [and] doing what you need to do to help counteract that,” she added.

At the same time, mental health day policies can help “raise a red flag” for students with chronic mental health problems, said Massachusetts State Representative Carol Doherty, whose bill, which died in committee this year, would have allowed for two mental health absences per semester without a doctor’s excuse.

“We need to pay attention to those kids who have a record of staying home and address that, not just call the truant officer after them,” Doherty said. “I think that it’s a signal for schools, for guidance counselors and others to pay attention to those records.”

Many of these bills, including Doherty’s, contain provisions instructing school mental health professionals to reach out to students who take absences for mental health reasons. Others passed alongside proposals to include mental health instruction in the health curriculum or to print suicide prevention resources on student ID cards.

Lishaun Francis, director of behavioral health at Children Now, an advocacy group, said schools should treat mental health like physical health.

“If we had a system where we saw a student who was missing school 10 times a month, because they kept getting this bone fracture, or this broken leg, we would ask what’s going on, right?” Francis said. “It wouldn’t be okay to us to just say, ‘Oh, they’re out sick.’ So yes, in that vein, I think there should be room for people to be able to deal with their mental health at home or with their provider. At the same time, I think we should be asking why.”

But even with protocol in place to monitor students with repeated absences, mental health day legislation has encountered opposition.

Alexandra Asay, 18, a recent high school graduate from Eagle, Idaho, who launched an unsuccessful petition in January to encourage her district to allow mental health days, said while fellow students were mostly supportive of her petition, she faced criticism from adults.

“They were like, ‘There’s no need for that, kids just need to toughen up,’” she said.

Some mental health professionals fear that this legislation might actually make it harder for students to access mental health support.

Glenn Xavier, a social worker at Hamden Middle School in southern Connecticut, said he worries that mental health days won’t help students whose parents can’t take a day off of work to care for them or those who don’t have supportive home environments. It would be better, Xavier said, for these students to be at school, where there are often counselors and school psychologists.

“For students that are in areas of poverty, I don’t really see it being supportive to them,” he said. “Yes, our kids are suffering from mental health. But who’s going to help them?”

Most mental health day laws are no more than a year old, so advocates and lawmakers say it’s too soon to measure the impact they will have on student mental health and attendance rates. A 2020 report from the Health Impact Project found that “[t]he effects of allowing excused absences for behavioral health concerns in school attendance policies are not well researched.”

Stigma and lack of awareness may be limiting the legislation’s effects. Xavier said he didn’t know of any students who had requested a mental health wellness day at his middle school, although Connecticut’s law was passed in June of last year. Francis, of Children Now, noted that parents might not want to admit their child was missing school for mental health reasons.

California’s mental health day law also took effect in 2021, but high school senior Megan Haubrich of Modesto said she wasn’t aware of it.

“I’ve certainly taken my fair share [of mental health days], but I just mark it as illness,” Haubrich said. “No one’s talked about it; there’s been nothing within the district that kind of outwardly promotes it.”

Even upon learning about the policy, Haubrich said she probably wouldn’t feel comfortable telling her school she was taking a mental health day.

“Interacting with administration is a little bit different than interacting with your peers,” she said. “I feel like there’s still, the older you are, the more old school view on mental health.”

• Arizona • IowaStates that have passed student mental health day legislation:

• California

• Colorado

• Connecticut

• Illinois

• Kentucky

• Maine

• Maryland

• Nevada

• Oregon

• Utah

• Virginia

• WashingtonStates weighing student mental health day legislation:

• Massachusetts

• Missouri

• New Jersey

• New Mexico

• New York

• Pennsylvania

***

Sadie Bograd is a freelance journalist based in New Haven, Connecticut, covering education and politics. She is pursuing a degree in urban studies at Yale University.