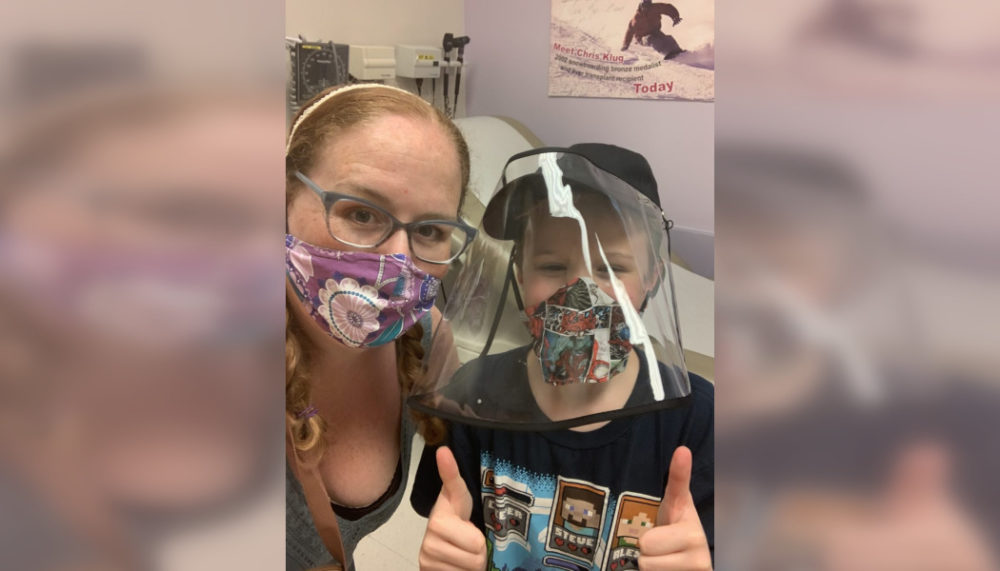

Tasha Nelson

Jack Nelson, a 10-year-old with cystic fibrosis, won’t be allowed on social media until he’s older and can understand the hateful comments that may be directed at him, his mother, Tasha Nelson, said.

In a widely shared Facebook video from 2019, mom Tasha Nelson discusses her family’s struggle to cover the sky-high costs of prescription drugs and other medical care required for her 10-year-old son Jack, who has cystic fibrosis.

At the time, she was very pregnant with another child, which prompted someone to privately, venomously post a response. Who, the hateful messenger asked, dared to have another baby, given that she already had a child with disabilities? How disgusting is that?

“It often makes me feel as though the public at large would like families with disabilities to live out of sight and remain out of mind,” the Manassas, Va. mother said. “That is not something we are willing to do. Families with disabilities exist; we are fabulous and wonderful people that deserve to take up the same space as our typical peers.”

Nelson has read enough bullying social media posts targeting disabled people that she is hyper-cautious about ensuring that Jack doesn’t find his way to those sites. At least, not until he is old and resilient enough to endure the hatred that may be directed at him on social media.

Research: Risks of depression and suicidal thoughts were higher for disabled students

A 2019 survey of 20,000 youth, “The Ruderman White Paper on Social Media, Cyberbullying, and Mental Health: A Comparison of Adolescents With and Without Disabilities,” concluded that almost 30% of students with disabilities experienced cyberbullying as a victim, perpetrator, or both, while the respective figure was 20% for students without disabilities.

A 2019 survey of 20,000 youth, “The Ruderman White Paper on Social Media, Cyberbullying, and Mental Health: A Comparison of Adolescents With and Without Disabilities,” concluded that almost 30% of students with disabilities experienced cyberbullying as a victim, perpetrator, or both, while the respective figure was 20% for students without disabilities.

It also found that 45% of disabled students and 31% of non-disabled students experienced depression as a result of being cyberbullied. Also, 38% of cyberbullying victims with disabilities reported considering suicide, which compared to 23% of victims without disabilities.

On the flip side, those researchers wrote, students with disabilities were more likely to report that social media helps them feel better about themselves than were students without disabilities.

Those researchers also concluded that youth with disabilities used social media only slightly more frequently than those without disabilities.

Social media also has positive effects for youth with disabilities

Social media allows youth with disabilities to connect with others in ways that may not be possible given their everyday challenges, said criminology professor Sameer Hinduja, co-director of the Cyberbullying Research Center at Florida Atlantic University.

Apart from helping them socialize, social media can widen their circle of peers and acquaintances, providing them “with encouragement, support, mentorship, guidance and meaningful friendships,” Hinduja said. “Additionally, social media use is often viewed as primarily passive. But [it] can be actively used by those with disabilities to showcase their unique talents and abilities.”

Eighteen-year-old Liz Adams was born with Goldenhar syndrome, a cranio-facial birth defect that disfigured the right side of her face. She has a cleft lip and palate, and an underdeveloped eye, ear and jaw. With Courageously Kind as her screen name, the upstate New York resident openly talks about her disability and hosts chats with a range of experts and everyday people on Instagram and Facebook. A year ago, she and her twin sister Maddie Adams, who doesn’t have the same syndrome, launched their Courageously Kind podcast.

Liz Adams’ largest audience is on TikTok, where she has 110, 400 followers and 1.9 million likes. It’s also the place where she receives the most hate, mainly from people who pop up, then quickly disappear, during her livestream talks.

“Anyone on social media knows that it can become toxic quickly,” Adams said. “However, I find that it has the potential to be a place for education, ally-ship and a place to grow. I have gotten really vulgar and upsetting comments, but I don’t pay them any attention.”

Liz Adams

Liz Adams, Courageously Kind podcast co-founder.

Because of how she looks, she expects to always attract mean-spirited trolls on social media. She chooses, therefore, to focus her energy on the hundreds of comments that are “filled with kindness and love.”

Tasha Nelson has a similar approach. Previously, she responded to negative comments, mostly hoping to debunk myths and raise awareness about disabled people. Typically, when corrected, the hateful commenter didn’t respond or comment further, she said, though, occasionally, one of them would respond by posting a laughing emoji or some other sign that they were dismissing her.

“People who take the time out of their day to purposefully compose something to degrade another person are not worth my time or attention,” said Nelson, who now ignores hateful posts.

Comments aren’t the place to combat disinformation, said Nelson, who, instead, chooses to pen informational op-eds on news sites and letters to the editor. Sometimes, she added, she tweets an anti-hatred message that generates an apology from a hater.

As a University of Florida doctoral student, Laken Brooks, 26, is exploring how digital technologies, storytelling and personal wellness intersect. She has chronic depression, anxiety, tinnitus and painful endometriosis-like symptoms. She’s confronted discriminatory comments and medical disinformation on her Facebook and TikTok pages as she discussed how she manages those chronic illnesses.

Brooks used to try to convince people about the harms of being misinformed about disabled people and spreading that misinformation. These days, rather than trying to persuade and re-direct hateful commenters who, to her, often dig in their heels and cling to those stereotypes, she shares helpful resources and information with other disabled people.

That’s one of the positives that offsets the negatives of online communities, Brooks said. She remains on social media, she added, partly because confronting those platforms’ information and disinformation is important to her work as an advocate for herself and for others.

Likewise, New Yorker Adams has considered leaving social media. But her work with Courageously Kind is one of the main reasons she stays.

Whenever negative comments get her down, she said, she revisits a quote by Theodore Roosevelt: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena … ”

Adams continued: “I may sound like a broken record on TikTok, but when people choose to interact with the content of disabled creators, they are choosing to lift these voices and ensure that they are heard.”

Tools for mitigating and navigating negativity on social media

Florida criminologist Hinuja has suggested that parents start with ensuring their child is not seeking to define and measure his or her identity and self-worth based on their tally of followers, friends, likes and other forms of validation on social media. “Ideally,” he said, “their identity is anchored to something much more stable, whether it is the person they are becoming, how bright their future can be, their faith, family, et cetera.”

According to researchers at the Ruderman Family Foundation, parents should encourage their children to use social media safely and responsibly, and help them not fall victim. That means talking to their children about what to do if they or someone they know is cyberbullied; encouraging them to only interact with people they know and trust; encouraging them to act kindly towards others on social media; and regularly monitoring their social media use. It also means acting immediately if they find out their children are victims and/or perpetrators of cyberbullying by telling appropriate officials about the incidents and seeking help from mental health care providers, if needed.

“There are two sides to social media,” Virginia mom Nelson said. “It can be a powerful tool for good but, when misused, it spreads dangerous disinformation and lends that same power to the uninformed and hateful.”