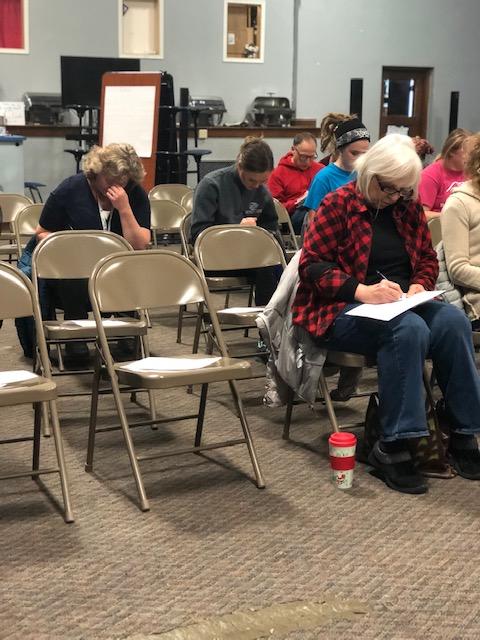

Photos by La'Ketta Caldwell

Milwaukee high school senior Amira Adams (left) assisted La’ketta Caldwell, arts director for the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater Milwaukee, in an anti-bias training at the Boys & Girls Club of Baraboo.

When a photo of students giving a Hitler salute in Baraboo, Wis., went viral last year, the repercussions were immediate.

The photo generated widespread media coverage and outrage. Suddenly, Baraboo, a town of about 12,000, was in the news, and people worldwide condemned the youth who took part and questioned what they were being taught.

A youth-serving organization stepped forward in response.

“We as a community had to make some sort of a move,” said Karen DeSanto, executive director of Boys & Girls Clubs of West Central Wisconsin.

She organized a training designed not only to counter racial and ethnic bias, but to do so in an interactive manner influenced by the arts.

“It was one of the most profound [workshops] I’ve ever been to,” DeSanto said.

The photo in Baraboo showed a group of about 60 boys in suits standing on the steps of the Sauk County Courthouse with their right arms upraised in salute. It was taken in May just prior to the Baraboo High School prom, but gained notice when it was posted on social media in November at #BarabooProud,

The response that followed included posts by some students saying that racist statements and attitudes took place at school with little reprisal, according to the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel.

The head of the school board publicly apologized and community leaders took action.

Teaching adults who work with youth

DeSanto contacted La’Ketta Caldwell, arts director for the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater Milwaukee, who also does social justice and inclusiveness trainings.

They set up an anti-bias training session for staff at the club, something DeSanto had already been considering.

“We took it a step further and invited people in the community who work with youth,” she said.

About 40 people, including local teachers, artists, youth theater directors and Baraboo Mayor Mike Palm took part.

Milwaukee high school senior Amira Adams helped Caldwell lead the training.

“My goal [in Baraboo] was for people to have a safe space to talk,” Caldwell said. “Art is a safe space to begin conversations that are difficult and uncomfortable.”

Caldwell has a degree in education and theater. In Milwaukee, she developed Can You Hear Us Now?, a program using drama and the arts to help young people deal with community issues.

One workshop activity began with large sheets of paper on the wall each labeled with one word: black, white, Asian, rich, poor, homeless and other descriptors.

Each participant was asked to write on the paper what they associated with the word or what they had heard others express.

DeSanto recalled the negative adjectives on the sheet labeled homeless: stupid, dirty, poor, lazy, black, takers, money suckers.

“The papers filled up with just terrible things,” she said. The group walked together from paper to paper.

“La’Ketta read all the words and we as a group had to repeat them back. It was very emotional and very telling and very eye-opening,” DeSanto said.

It was difficult to write the words and difficult to say them, she said.

“It made us feel dirty and judgmental,” she said. It had a profound impact. It helped people realize that regardless of what you really feel, these biases are there, she said.

“You make judgments,” she said. But the recognition allows people to move forward, she said.

A broken heart

In another exercise, Caldwell gave each participant a picture of a cracked heart. They were asked to write the following on the picture:

- Their dream.

- A time when they were judged.

- A time when they judged someone else.

- A thing that broke their heart.

Then each person passed their paper to someone else in the group.

In addition to staff of the Boys & Girls Club of Baraboo, local teachers, artists, youth theater directors and Baraboo Mayor Mike Palm took part.

“Your goal is to write a letter to this heart,” Caldwell told them. They each wrote a letter to the heart they were given and then read it out loud.

Some people cried, she said.

The exercise put everybody on the same page, Caldwell said. It showed “the humanity of everybody,” she said.

“We’ve all had a dream. We’ve all been judged. We’ve all judged someone else and we’ve all had our heart broken,” she said.

In order to work with youth, adults have to understand their own biases, Caldwell said.

“They had an opportunity to honestly recognize the biases they have,” she said.

The idea was also that workshop participants would share their experience with others.

“I wanted to show what the club can provide to the community — a training not necessarily offered anywhere else,” DeSanto said.

One workshop isn’t the entire fix, both Caldwell and DeSanto said. But it was a start.

Media glare felt traumatic

Baraboo has a mostly white population. But the Boys & Girls Club is more diverse than the general population, DeSanto said.

She was concerned about the media spotlight on the boys involved, some of whom attend the club. The community received a dose of hate in response to the photo, she said.

The boys were shamed, the families shamed and businesses shamed.

“This is a defining moment” for the boys, the photographer, even the school superintendent, she said. “I’m anxious to see what some of the boys will do going forward,” she said.

Since mid-November when the photo garnered huge attention, Palm, the mayor, has led the community in developing a response. An initial meeting was held at Baraboo High School in late November.

Ten days later, community members identified their concerns and priorities. On Dec. 17, the community created a 12-step action plan that included improving Holocaust education, bringing in speakers on diversity and equality, adopting a sister city and introducing restorative justice practices to the schools.

It was natural for Palm to attend the Boys & Girls Club workshop — he already was part of a mentoring initiative there. And he was in the Boys Club in Milwaukee in the late 1950s and early ’60s in his preteen and teen years.

The viral photo hit the town hard, he said.

“It was akin to losing someone in a sudden death. Everyone was walking around with a sense of loss,” he said.

“There are a lot of good people here” and suddenly they felt tarnished, he said.

“Racial prejudice is everywhere in all the country. The photo put a face to it in our community and we’re doing something about it,” he said.

He acknowledged that not everyone in the community is on board. Some dismiss the photo, saying the boys didn’t mean anything.

In December an anti-Semitic video appeared on social media and fliers warned people not to attend the next community event. One flier was posted at Jack Young Middle School, according to new media reports.