shutter_o/Shutterstock.com

.

The next generation is responsible for protecting an environment that they may not know how to connect with. As someone who sees nature as a place where we can examine what it means to be alive, I had a rude awakening last year while supervising a camping trip for 70 middle school students with a local nonprofit organization. I learned how poorly prepared the students were to meet their own needs (such as bringing soap or a flashlight), and how focused they were on performing near-miss stunts and searching for wild animals.

School break programs that involve environmental outings are one of the few opportunities for youth to gain an identity that is independent from their regular social rhythms and establish a connection with nature beyond what is represented in popular media. Our aim, when we take them on hiking, canoe or camping trips, is to show them pristine places in nature that are far from the lands they live on, a classroom that naturally fosters self-determination, and healthy ways in which they can take refuge in difficult situations. Young people participating in outdoor-focused programs can show increased personal competence and more quality social interactions.

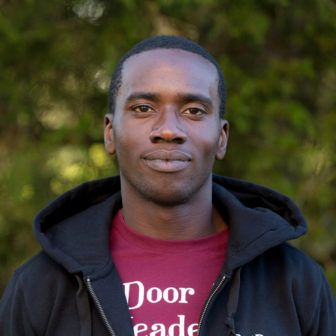

Mayowa Ogunjobi

However, we still need to evaluate whether we are presenting our environmental programs in a way that is appealing or relevant for all of them. The traditional media depiction of outdoor activity participants is strong white men having extreme fun, which leads to conclusions that do not inspire youths from disenfranchised groups to join outdoor activities.

Ambreen Tariq, founder of Brown People Camping, is a Muslim American who uses her time outdoors to cut out all the negative partisan voices that make her feel like the “other.” She leads her organization to counter the dominant ideas that depict what it means to be an outdoor enthusiast. Nature is a place where all young people should be able to bridge the gap between who they are and who they want to be.

As we support youths in our work as program administrators and day-to-day activity leaders, we must consider the diverse perspectives of the disenfranchised groups we are trying to connect with, examine our own prejudices and seek to dismantle existing power systems that prevent outdoor- and nature-based experiences from becoming sustainable practices that will impact the rest of their lives. With their snacks and sleeping bags, youths in our environmental programs carry their community’s historic experiences of restricted access to outdoor spaces, feelings of not being welcome in the chic outdoor community, familial imprints of places they “don’t dare go” and the serious access issues presented by equipment and transportation costs.

If our goal is for the next generation to use the term outdoors synonymously with escape, we must show awareness and openness in our communication and embed these values in all our procedures. When NOLS, the National Outdoor Leadership School, recognized that it had little diversity out of several hundred instructors, it began to close the gap by using real examples of organizational prejudice to develop a guide for inclusion in the outdoors. By confronting oppression, NOLS transferred power to disenfranchised groups and grew in its ability to serve youth.

During environmental outings, we want to instill passion. To do this more effectively, we must minimize the social power dynamics that make youth feel weak, unwelcome or humiliated. If safety and time are major concerns, we must give them active roles that empower them to actively seek wise choices under responsibility for the group. If we develop a well-rounded understanding of their expectations before the program begins and hold them to high standards throughout, we can remain relevant in a country that is becoming increasingly diverse. I hope that we can follow through.

Mayowa Ogunjobi is a wilderness first responder and a master’s candidate in educational administration at the University of Florida. When he is not writing his blog, he leads outdoor trips in Tallahassee, Florida.