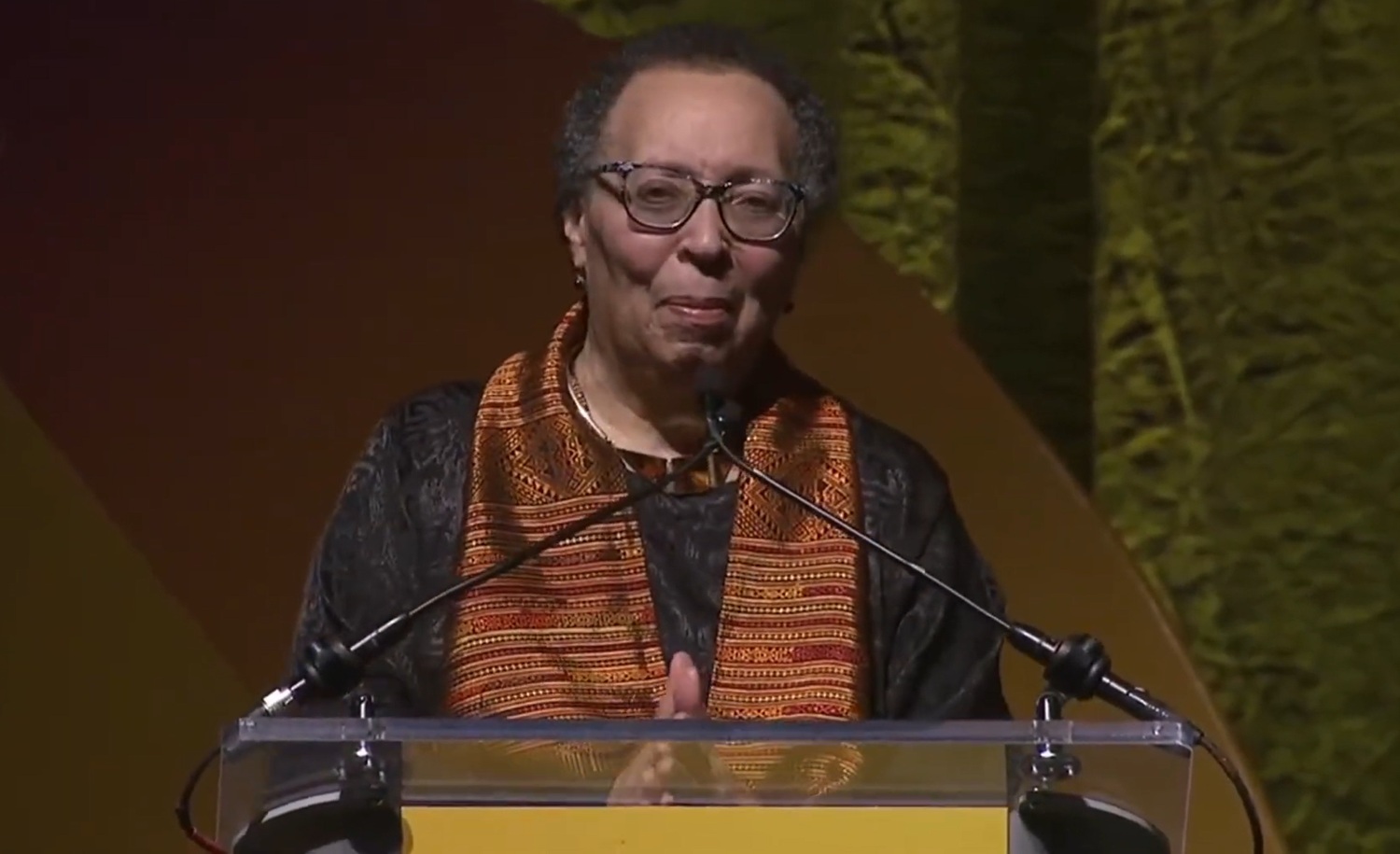

Karen Pittman is editor-in-chief of Youth Today, a founding partner of Knowledge to Power Catalysts, and co-founder of the Forum for Youth Investment, which she led with Merita Irby for more than 20 years. Frequently referred to as the godmother of positive youth development, she has spent her career bringing research on adolescent development into policy and practice to help leaders realize they can do more than help a few young people “beat the odds” — they can make systemic changes that actually “change the odds.” On February 13, Karen received the NEA Foundation’s 2026 Outstanding Service to Public Education Award. Previous recipients include Kent McGuire, Linda Darling-Hammond, Sesame Street, Mister Rogers, and President Clinton. I caught up with Karen after the award to ask her to reflect further on her acceptance remarks.

Karen Pittman is editor-in-chief of Youth Today, a founding partner of Knowledge to Power Catalysts, and co-founder of the Forum for Youth Investment, which she led with Merita Irby for more than 20 years. Frequently referred to as the godmother of positive youth development, she has spent her career bringing research on adolescent development into policy and practice to help leaders realize they can do more than help a few young people “beat the odds” — they can make systemic changes that actually “change the odds.” On February 13, Karen received the NEA Foundation’s 2026 Outstanding Service to Public Education Award. Previous recipients include Kent McGuire, Linda Darling-Hammond, Sesame Street, Mister Rogers, and President Clinton. I caught up with Karen after the award to ask her to reflect further on her acceptance remarks.

![]()

![]()

Q: You’ve received many awards over the years, but this one really surprised you. Why?

Karen Pittman: While I’m an adamant advocate for public education, I’m not an educator in the traditional use of the word. My work has always focused on learning and development. But I’ve never been a classroom teacher. I’ve never done research on school improvement or academic learning. I have, however, made a concerted effort over the past ten years to spend more time with education researchers and transformation leaders to help illuminate the relevance of positive youth development to their renewed commitment to engaging the whole child. I’ve always been welcomed. But there have been plenty of times when I’ve questioned my impact.

This award, more than any other I’ve received, tells me that I —

and with me the allied youth fields — have succeeded in making our case.

Q: You shared the fact that your goal as you entered college was to become a middle school math teacher, but your experiences at an educational camp for teens changed your career trajectory. Tell us more about your experiences.

Karen Pittman: In the mid-1960s, David Weikart, the founder of High Scope Educational Research Foundation and the Perry Preschool Project, started an educational summer camp for teens. The camp was a setting for testing the effectiveness of his learning philosophy, which was successfully demonstrated for preschoolers, on teenagers. Each year, Dave came to Oberlin College (his alma mater) to recruit students interested in education to become camp counselors. I spent eight weeks each summer with 60 to 80 12-to 18-year-olds. Their job was to immerse themselves in becoming part of a learning community with counselors only a few years older than them.

As counselors, we spent as much time making weekly room and table assignments as we did planning 45-minute learning explorations and week-long, hands-on language, arts and science projects. We understood the power of active learning because we were experiencing it along with the teens. By the time I was ready to do student teaching, it was clear to me that what I had internalized would make it difficult for me to teach in a traditional school and equally difficult to work in a traditional youth organization. I had no choice but to continue to find ways to promote active learning. Twenty-five years after my camp experiences, I had the honor of writing the foreword to Learning Comes to Life: An Active Learning Program for Teens, published in 1996 and written by Ellen Ilfeld, one of my campers who went on to work at High Scope.

Q: You got spontaneous applause when you mentioned that your goal to become a teacher was directly related to the excellent education you got in the Washington, D.C. public schools because your junior and senior high schools were part of a “grand experiment.” Tell us more.

Karen Pittman: The District of Columbia public schools experienced some of the steepest enrollment declines in the county in the 1960’s as white families moved to the neighboring counties in Maryland and Virginia. DCPS implemented major reforms to modernize quickly to become competitive with suburban schools. They created specialized programs emphasizing science, arts and college preparation. They created selective academic secondary schools that introduced academic tracks into comprehensive schools and introduced progressive pedagogy and innovative curricula. I’ve done a bit of research to confirm this history. But it very much matches my experience.

[Related: From systems leadership to ecosystems stewardship — A next step for OST intermediaries?]

I went to junior and senior high school with kids from across the city who converged via public transportation at two under-enrolled schools. I understand, from history, that the lower tracks remained largely segregated and did not benefit equally from innovative practices. But the upper tracks were racially and economically diverse, taught by an equally diverse staff. And the quality and progressiveness of the teaching was incredible. I experienced looping, team teaching, project-based learning and block scheduling. In junior high, we did triple period lab experiments. Girls were required to take shop while boys took home ec. In high school, we spent our afternoons in an interdisciplinary humanities block co-taught by literature, art, history and civics teachers. The experiment slowed white flight but ultimately was unable to stop it. But it instilled in me and my peers a sense of agency over our educational journeys that had a huge impact on our futures.

Q: Do you see any parallels between the learning environment you experienced in your public schools, the active learning environment you helped create at camp with Weikart and the learning environments you are advocating be stewarded across ecosystems?

Karen Pittman: Yes, although I hadn’t thought about the connection until preparing my remarks for this award. Agency, engagement and community are the common threads that tie my early experiences to my latest advocacy work. When asked to describe their high school years, people frequently talk about navigating cliques and being bored. I didn’t experience either. My academic classes were tracked, but I spent time in electives, extracurricular activities and common spaces with students across all tracks. I may have rose-colored glasses on, but I feel like there was a sense of mutual respect not only between the races, but also between geeks, hippies and jocks. I think this respect came from the fact that teachers worked to ensure that every student had an outlet for their passion.

[Related: Coaching, not correction — The shift youth-serving systems need to build real leaders]

I looked at my high school yearbook a few years ago to test this theory — every student had at least two extracurricular activities next to their name. And almost every club was racially integrated. So, while students weren’t equally privy to progressive pedagogies, they were the beneficiaries of a belief that racially and economically diverse students can form a community if they first find public affirmation for who they are. This affirmation was the hallmark of Weikart’s camp for teenagers. And it is the reason Merita and I talk so incessantly about the need to optimize connections within and across the learning ecosystem.