Once program co-founder asks, ‘Why couldn’t you just teach every kid in America to read one-on-one?’

High-dosage tutoring is one of the most effective tools to help students recover from lost learning, including in subjects like reading, where many are far behind.

But what if schools didn’t wait until students fell behind? What if all kindergartners got a reading tutor from the start?

That’s what the early-literacy tutoring company Once is testing out. They have a hunch the results will look good.

Courtesy of Matt Pasternack

Matt Pasternack, co-founder and chief executive, Once.

By contracting with schools and tracking outcomes, the company hopes to convince more schools and districts to invest in early literacy tutoring, according to Matt Pasternack, Once’s chief executive and co-founder.

“It sounds crazy, but why couldn’t you just teach every kid in America to read one-on-one?” Pasternack said.

The program includes daily, 15-minute sessions during school, but is flexible, according to Pasternack.

Pasternack said the curriculum is informed by the science of reading, a growing movement to change literacy instruction and re-emphasize phonics. Alone with a tutor, students are taught to recognize letters, the sounds that they make and how they blend to form words.

By the end of the year, Pasternack hopes all students can decode fluently, which he thinks will enable them to learn “more autonomously in every grade afterward.”

The two-time grantee received roughly half-a-million dollars from Accelerate, a national nonprofit that has given roughly $21 million to various groups to scale tutoring efforts post-pandemic. Once worked with “hundreds” of students during the 2022-2023 school year and will work with over 1,000 during the upcoming school year, according to Pasternack. The program has been offered at public, charter and private schools in states including California, Hawaii, Texas, New York, and Ohio, and in Washington, D.C.

The program costs schools about $400 per student and has been given to entire classes and as an intervention for selected students.

Schools are required to provide personnel to be tutors, such as paraprofessionals or other existing school staff. Once provides a scripted curriculum and ongoing coaching. Pasternack said school staff are generally not compensated for the additional tutoring duties, but the program is working to partner with local universities so they can get course credit.

One-on-one key to teaching phonics

Pasternack said “one-on-one instruction simplifies the implementation of the science of reading.”

He said phonics is challenging to execute in large classrooms because it requires “near-perfect classroom management.”

“In order to teach those types of skills, you need to hear what every single child is saying,” Pasternack said.

“Master teachers” excel at large-group instruction, but many others struggle, Pasternack said.

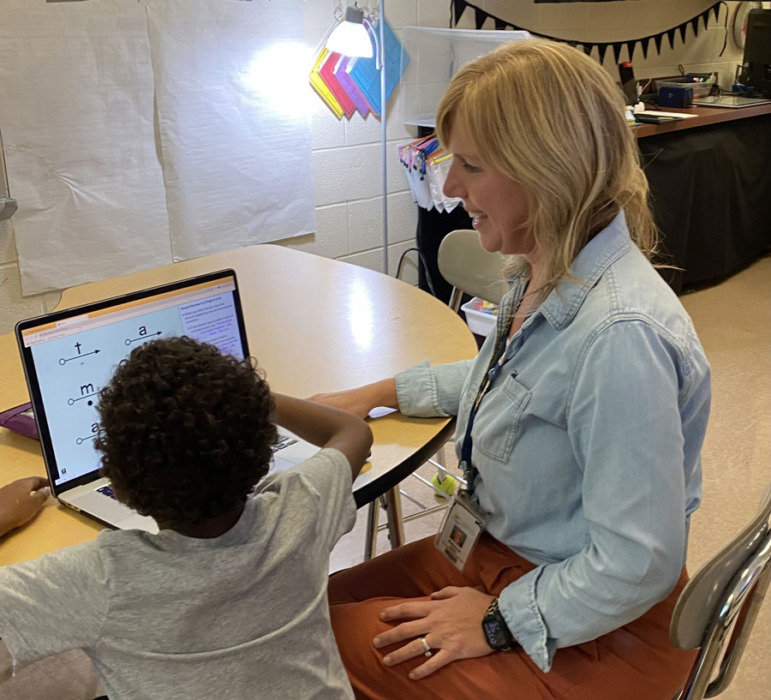

Courtesy of Rebecca Kette

Rebecca Kette tutors a kindergartener using the Once program.

Rebecca Kette, an intervention specialist at Orchard STEM School in Cleveland and a former Once tutor and coordinator, said one-on-one time was beneficial to meet her students’ needs.

“I think a constant struggle for classroom teachers is that individualized attention for children,” Kette said.

Patrick Proctor, Department Chair, Teaching, Curriculum, and Society Professor, at Boston College and a professor focused on bilingual education and literacy, said without individualized attention, teachers can’t meet students’ phonic needs.

“A whole-group phonic program is not designed to meet every student where they are at, but rather is focused at on-average expectations of where students should be,” Proctor said in an email.

‘Everything in package’

Once tutors get two half-days of training upfront followed by weekly sessions with Once coaches. All tutor sessions are recorded and viewed by the coaches, who provide feedback during weekly meetings.

Courtesy of Matthew Kraft

Matthew Kraft, education and economics professor at Brown University.

“The way that they tutor and train people, you understand the curriculum and are able to deliver it,” said Joseph Salazar, a Once tutor and coordinator and an English as a Second Language teacher at Seaton Elementary in Washington, D.C.

Salazar said he knows how much goes into designing lessons, so he appreciates Once’s script and curriculum. Even if he didn’t have teaching experience, he said he’d feel confident.

“Once provides everything in a package,” Salazar said.

Empowering school employees, like paraprofessionals who may not have prior experience in literacy instruction, is important for scalability, according to Matthew Kraft, an education and economics professor at Brown University who has studied tutoring expansion models.

“Scaling tutoring requires expanding the pool of tutors,” Kraft said in an email. “Paraprofessionals offer an attractive pool of labor for tutoring because they have lots of experience working with students and they are already employed by school districts.”

Early results and criticism

Pasternack said research about Once is “extremely preliminary.” He’s “hopeful” more results will be available “by the middle of this year.”

A report by LXD Research highlighting the impact of the Once program on students at seven schools last academic year concluded there was a positive correlation between Once lessons and students’ scores on the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS) assessment.

“Overall, the more lesson cycles students completed in Once, the higher their scores,” Rachel Schechter, the report’s author, writes.

Salazar said that of the six students he tutored last year, all started below benchmark and five met or exceeded reading-level benchmarks by the end.

Kette said her students showed “big gains” in oral-reading fluency.

Laura Justice, a distinguished professor at Ohio State’s Department of Educational Studies and the executive director of its Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy, agreed there is “strong evidence” for the efficacy of small-group lessons on decoding and comprehension skills. But before scaling a program like Once, it’s important for claims to be “assessed using experimental methods,” she said.

Justice said there isn’t evidence supporting the idea that one-on-one is more effective than small-group tutoring.

Pasternack said he’s open to exploring small groups, but that it would pose several challenges for the program.

“All the kids need to say the exact same sound at the same moment otherwise they’re going to listen to each other, rather than reading,” Pasternack said.

Justice also said it should be tested whether daily sessions really boost outcomes more than sessions two or three times per week.

“There is a threshold of additional instruction that is needed to help children advance, but instruction above that threshold does not necessarily pay off,” she said in an email.

Pasternack said that Once has “documented cases” of students that missed sessions and attended approximately two or three sessions per week.

“The kid just moves half as quickly,” Pasternack said. “You can’t move faster in less time.”

[Related: Every school a community school. Every community a learning community.]

Proctor said he’s skeptical about the logistics of scaling Once. Tutoring a class of 16 students one-on-one for 15 minutes each amounts to four hours of instructional time a day. But, since school days are complicated, he said it would take longer.

“Likely it wouldn’t happen every day for every child because schedules are challenging,” Proctor wrote. “Multiply that by every day of the school year and you get a lot of slippage.”

Pasternack responded by saying schools aren’t required to use Once programming everyday.

“We work with each school to create a schedule that works for that school,” Pasternack said.

Proctor also challenged the belief that schools “need to be going so heavy on phonics and decoding in kindergarten.”

“The point of kindergarten is to develop social skills, introduce children to literacy, language, and numeracy, explore music, play,” he said.

But Pasternack said declining kindergarten enrollment makes him think current standards may not be working.

Additionally, Pasternack said Once isn’t just about decoding. Each lesson emphasizes phonemic awareness, includes comprehension questions, and revolves around reading an episode, he said, “in a suspenseful and engaging epic journey of a group of animals searching for safety, wisdom and connection.”

Ultimately, Pasternack said he hopes Once can build on existing research and “broaden the conversation.”

“We don’t want to play games with the data,” he said. “We are truly curious. Does scripted, explicit, one-on-one instruction in foundational literacy change the trajectories of the students who receive it in kindergarten?”

***

Julian Roberts-Grmela is a free-lance journalist based in Brooklyn, New York. His work, focusing on education, has appeared in several publications, including The 74, The New York Times, The Chronicle of Higher Education, New York Daily News, Gothamist, City Limits, and Chalkbeat.

This story was produced by The 74, a non-profit, independent news organization focused on education in America.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Overdeck Family Foundation provide financial support to both Accelerate and The 74.