The bright lights, whirring tools and overstimulation of the dentist’s office trigger anxiety in Aurélie Brown’s daughter, Suzie Brown.

“The first time I took her to a dentist, she was two and a half and she was just not having any of it,” Brown said, of her now 8-year-old child, who has Cohen syndrome, a disorder marked by small head size, developmental and other delays.

“The sounds, everything was too much,” the mother added. “We gave up on it for a long time, honestly.”

Suzie is among roughly one in five children and one in every two adults worldwide with anxiety or major fear about being treated by a dentist. Those stresses often are especially acute for children and young adults with special physical, developmental, intellectual or behavioral needs.

There’s not enough specialized dental care

More than 3 million persons younger than 18 were reported to have cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, autism or other disabilities in 2019, according to the U.S. Census. Since many general dentists don’t treat children with disabilities, that means millions of parents may find it challenging to find a dentist to care for their child.

“With Cohen syndrome, Suzie’s mouth is very small and her airways are very small,” Brown said, of that genetic disorder. “She doesn’t know how to spit. She doesn’t know how to brush her teeth. We have to help her.”

[Related: Tips for finding specialized dental treatment for disabled youth]

Dental care for children with special needs requires not only specialized knowledge but additional attention and accommodations beyond the usual care, according to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Accommodations include changes such as turning down the lights in the examination room, keeping the room quiet and without clutter, or placing the child in a private room, instead of a larger one where pediatric dentists often treat patients who are seated side by side.

In a small pilot study, University of Southern California School of Dentistry and Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles researchers found that accommodations such as blackout curtains, calming music, lowered lights and weighted body wraps resulted in fewer signs of anxiety, stress and discomfort among children ages six through 12 with autism during their dental visits. Similar studies are in progress.

Pediatric dentists receive training to handle patients with disabilities, but not all offices can make these types of accommodations.

Courtesy of Dr. David Jourabchi

Dr. David Jourabchi

“Treating people with disabilities or people with special health care needs takes longer,” said Dr. David Jourabchi, a pediatric dentist in Phoenix who exclusively treats disabled patients.

Dentists treating disabled patients cannot see as many patients daily, Jourabchi added, and since insurance plans do not reimburse dentists more money for those longer visits, it can result in the practice losing money.

“A lot of providers won’t open their offices to those individuals or they’ll limit the services they offer,” continued Jourabchi, of Dentists for Special Needs. “At this point, it becomes very difficult to take insurance, give a patient special services and still be able to come out profitable.”

Though Jourabchi’s clinic does bill insurance companies for its services, for now, it still requires some donations to sustain its operation costs, he said.

Too few dentists means long waits

To make matters more difficult, there are not even enough pediatric dentists for the services needed.

There were nine pediatric dentists for every 100,000 U.S. kids, according to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry’s Dental Workforce Study. In 2018, there were 8,033 pediatric dentists, up from 4,213 in 2001. With those increases projected to continue, within a decade, the number of pediatric dentists per 100,000 kids will increase from nine to 14.

Without widespread dental offices to care for special needs, mom Aurélie Brown encountered offices without private rooms or ones where neither she nor her husband, David Brown, could stay with their daughter during exams. Even after the Browns found a clinic 90 minutes away from their home in State College, Pennsylvania, they waited 10 months for an appointment, mainly because of a backlog during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We were lucky because not everyone can take half of a day from work to drive hours away,” said Brown, co-executive director of Parent to Parent USA, which advocates for individuals whose disabilities demand specialized health care.

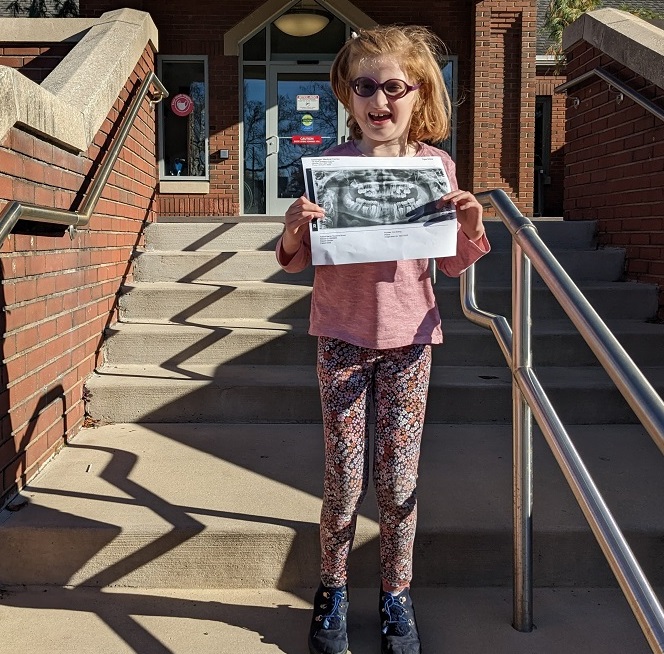

Courtesy of the Brown Family

Suzie Brown

The appointment went well — nearly six years after their first unsuccessful attempt. “That’s quite the win,” said Brown, of Suzie’s success that time. “They gave more time than other offices and let both of us go in with Suzie, so one of us could have a conversation with the doctor and the other one could help hold her down. They were welcoming.”

That was a relief for Brown, who’d been conflicted about scheduling her child to see a dentist. She knew about a child with Cohen syndrome who died following an adverse reaction to anesthesia in a dental office.

“It’s hard to not have that in the back of your mind when you’re looking for care,” Brown said. “The girl’s death highlights the need to find specialty care.”

Dentistry risks are greater for disabled children

More than 100,000 children are sedated in dental offices each year, according to a 2017 report in Pediatrics about a 4-year-old boy without disabilities who died shortly after receiving sedation in a dental office. Sedation risks are even higher for children with special needs. Because there is no mandate to specifically report deaths after dental sedation, it is unclear how many children have died from complications related to sedation.

What Jourabchi witnessed personally prompted his specialized practice. He grew up with an older cousin who was intellectually and developmentally disabled. “She would always get left behind in every way possible, even in dentistry,” he said. “She was one of the people who every time she needed dental work, she would need to be in an operating room.”

For some children, having dental work while sedated and monitored in a hospital operating room is the only option. That’s because the work is extensive or the child will not sit still for the dental work. But the amount of operating room space available to dentists is limited, forcing many patients to have long waits — sometimes six to 12 months — for the dental procedure.

“So for [my cousin], when she had an emergency, she had to wait two years for an operating room, and that’s just unrealistic,” Jourabchi added.

To ease the shortage of available slots, several dental organizations appealed to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in June 2022 to raise the amount insurance companies pay hospitals for dental surgeries from $200 to $2,000 to incentivize hospitals to prioritize keeping slots open for dental procedures. In response, that federal center included this change in its new rules for 2023.

Unattended dental problems can affect children’s development

Dental health is critical. Unchecked tooth decay can impair speech and chewing, resulting in poor digestion, nutrition and physical growth. Unchecked decay also can lead to severe pain and infection.

Almost 100% preventable, tooth decay is the single most common chronic childhood issue, according to an American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry report. The same report estimated that it costs $10,000 to treat a child’s case of severe tooth decay, and children miss 34 million school hours total each year due to dental issues.

“If you can’t get regular preventative care because it’s just too difficult and it’s not manageable in an outpatient setting, the child may end up going to either the emergency room or to scheduled surgery, with all of those potential adverse effects,” said clinical psychologist Melissa Riddle, chief of behavioral and social sciences research at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

“ER visits also tend to be managed more with medicine as opposed to actually addressing the problem,” said Dr. Margaret M. Grisius, director of oral and comprehensive health at the same institute, who previously spent 30 years practicing dentistry. “It’s managing the pain and making sure the infection is under control, but not really managing the root of the problem.”

***

Physician and journalist Dr. Tyeese Gaines is a content producer-commentator for Black America’s Health. She has reported for MSNBC and NBCBLK, and was medical editor for The Grio.