Homeless teenagers and young adults are arriving at emergency shelters with more acute needs, but shelter providers short of adequate staff and resources in the wake of the pandemic are less equipped to help them. In some places, youth face longer waitlists for shelter beds and few safe overnight alternatives.

“We’ve just heard lots and lots of reports from places that are having a hard time filling jobs or people leaving their jobs,” said Steve Berg, the vice president for programs and policy at the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

The average hourly wage for youth care workers at youth homeless shelters ranges from $14-23, according to compensation data company Payscale, and many workers left during the pandemic due to burnout and COVID-19 fears.

Now, as inflation rises alongside private sector wages, youth homeless shelters are unable to compete. Most shelters are run by charitable organizations that depend on both public dollars and private donors. Grant awards, government funding and donor pools can vary year-to-year, making it difficult to consistently raise wages and keep pace with costs of living increases.

The staffing crunch comes as understaffed homeless youth shelters are seeing referrals — and acute mental health needs — increase.

“There’s just not enough services and resources available to support the need in many communities,” and reduced shelter capacities have made it harder for the hotline to connect young people to the help they need, said Jeff Stern of the National Runaway Safeline, which operates a national hotline for runaway and homeless youth.

“This is just not the job for them.”

Thad Calabrese, a professor of public and nonprofit finance at New York University, said he was unsurprised that staffing is an issue for shelters. Youth care workers can find a job with equal pay in other industries, he said.

“I’m sure the cost of staff has increased, revenues have gone down and the amount of spending on COVID measures probably blew holes in some of these budgets,” Calabrese said.

In Chicago, The Night Ministry’s shelter for homeless 18-24-year-olds was required by the city’s stay-at-home orders to stay open for months at a time, said director of youth programs Betsy Carlson. The stress, long hours and fears of COVID-19 exposure drove some staff away, she said.

“A lot of times the idea that you’re doing something good for vulnerable people and the community is supposed to sort of make up for the fact that you don’t get paid very well. But a lot of times, it’s too much. People need to have enough to be able to live themselves.”

Jeff Stern, National Runaway Safeline

At Huckleberry House, an emergency youth shelter in San Francisco, some staff members are quitting after only six months, rather than a few years as in the past — and more departing staff choose to leave the field entirely, said Doug Styles, executive director of Huckleberry Youth Programs. Shelter staff have at least three years of college or equivalent experience, plus 40 hours of training and earn $21-$26.50 an hour.

“When the economy moves quickly like it has the last two years, in terms of pay for people, it’s very hard for nonprofit organizations to keep up with the market,” Styles said.

And in New Mexico, youth shelters run by Youth Development Inc. have struggled to hire care staff throughout the pandemic, said James Mader, YDI’s clinical manager for residential services.

“You’re dealing with challenging youth, and for a lot of people, this is just not the job for them. They think they can handle it, and then they’re gone,” Mader said. “And we’re not getting the people with a lot of experience or the education that’s oftentimes necessary to deal with the challenges.”

YDI youth care workers must have six months of experience working with youth and a high school degree. They earn $15.96 an hour, though Mader says he is trying to get that increased.

YDI needs 15 employees to staff its short-term youth shelter in Albuquerque, Amistad Crisis Shelter, and two transitional living homes. But it’s operating with only 12 now, and shifting staff members between locations and paying overtime to maintain coverage.

“We’re really just scraping by and still trying to maintain the counts at the houses,” Mader said.

Youth in need are “coming out of the woodwork”

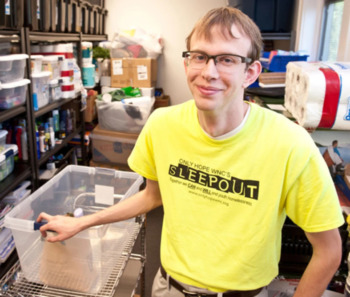

Courtesy of Michael Absher

Michael Absher, 34, spent his senior year of high school at a homeless shelter and now leads Only Hope WNC, which operates a small emergency shelter for older teenagers in Hendersonville, N.C.

Amistad’s funding depends, in part, on how many beds it fills: more homeless youth means more state money. But while more young adults are coming to the shelter in recent months, they have more needs.

“It’s picking up a little bit now, we’re getting more referrals,” Mader said. “But it seems to me like we’re getting more acute youth, more youth that need additional focus on psychiatric issues, or substance abuse issues or more major behavioral issues.”

Mader said specific help for those issues was likely harder to access during the pandemic. The responsibility to address these acute needs sometimes falls to Amistad now.

“So now, we’re behind the curve, and we’re trying to help these youth that are still in crisis,” Mader said.

It’s a trend others who serve youth are seeing nationally. The National Runaway Safeline has seen a 39% increase in the number of young people who contact the hotline due to mental health concerns, like depression and suicide.

Michael Absher, 34, spent his senior year of high school at a homeless shelter and now leads Only Hope WNC, which operates a small emergency shelter for older teenagers in Hendersonville, North Carolina.

Absher said he too has noticed more young people “coming out of the woodwork,” and more young people facing mental health and identity issues.

“People need to have enough to be able to live themselves.”

Courtsey of Kasie Caswell

Kasie Caswell recalled working 12-13 hour shifts three to four times a week, in addition to unpaid overnight stays as a back-up staff member at an Asheville, N.C. shelter.

Kasie Caswell, a former staff member at an Asheville, North Carolina shelter that served youth involved with the child welfare system as well as young people without a safe place to stay, recalled working 12-13 hour shifts three to four times a week, in addition to unpaid overnight stays as a back-up staff member.

Caswell said her hourly pay was “not too far above minimum wage.”

“Financially, it was a really tough position,” said Caswell. “I know a lot of people who went into that position as a kind of an entrance into the mental health field, and a lot of people really struggled not to burn out.”

Historically, like many nonprofits, youth homeless shelters have relied on workers’ commitment to their mission to make up for lower pay. But that may be changing, said Jeff Stern of the National Runaway Safeline.

“A lot of times, the idea that you’re doing something good for vulnerable people and the community is supposed to sort of make up for the fact that you don’t get paid very well,” he said. “But a lot of times, it’s too much. People need to have enough to be able to live themselves.”

***

Emily Davis is an Asheville, North Carolina-based journalist.