As a student in Washington, D.C., Kenvin Lacayo “hated school.” He disliked it so much that he stopped going for two years. But after his high school’s assistant principal pushed him to apply for a fellowship program placing young men of color in schools as early childhood educators, he soon became hooked.

Now 23, Lacayo is eighth-grade dean of a Washington middle school, a part-time student at Trinity Washington University, a youth policy consultant with the American Youth Policy Forum and on the board of We All Rise, an education and community empowerment nonprofit.

Youth Today spoke with Lacayo about his experiences teaching throughout the pandemic, how policymakers can support students and teachers and the importance of representation in education. Excerpts of the conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, are below.

The interview

Courtesy of Kenvin Lacayo

Kenvin Lacayo, 23, is eighth-grade dean at MacFarland Middle School in Washington, D.C.

Q: What was your experience working throughout the COVID-19 pandemic?

It was so weird, because I had to talk to everybody through a computer, but I still had to try to build relationships without getting to see anyone’s faces. You know, middle schoolers are middle schoolers — they’re going to feel awkward and if they can, they’re going to turn the camera off and hide their face.

But it was still very fulfilling, trying to adjust and build community. We had a karaoke night. I played a lot of Roblox with them. And then coming back from that, it was crazy. I had no idea what they looked like, but I knew what their voices sounded like. So I was like, ‘You’re this person, you’re that person!’ They were shocked.

Q: What do you think students lost by spending all that time out of school?

When they came back, you could definitely tell that they hadn’t been in school for a while. And I think that most educators would agree that made last year, extremely, extremely difficult — maybe one of the most difficult ever. There were a lot of [students] not being able to regulate their emotions, a lot of conflict between students and teachers over basic things that maybe usually would not actually bother them.

Even though it felt like the world had stopped, for a lot of us, a lot of things did not stop. There was still community violence; there was still gun violence, things still going on in our communities and in the communities of our students. And they didn’t have a school as a safe haven in that time.

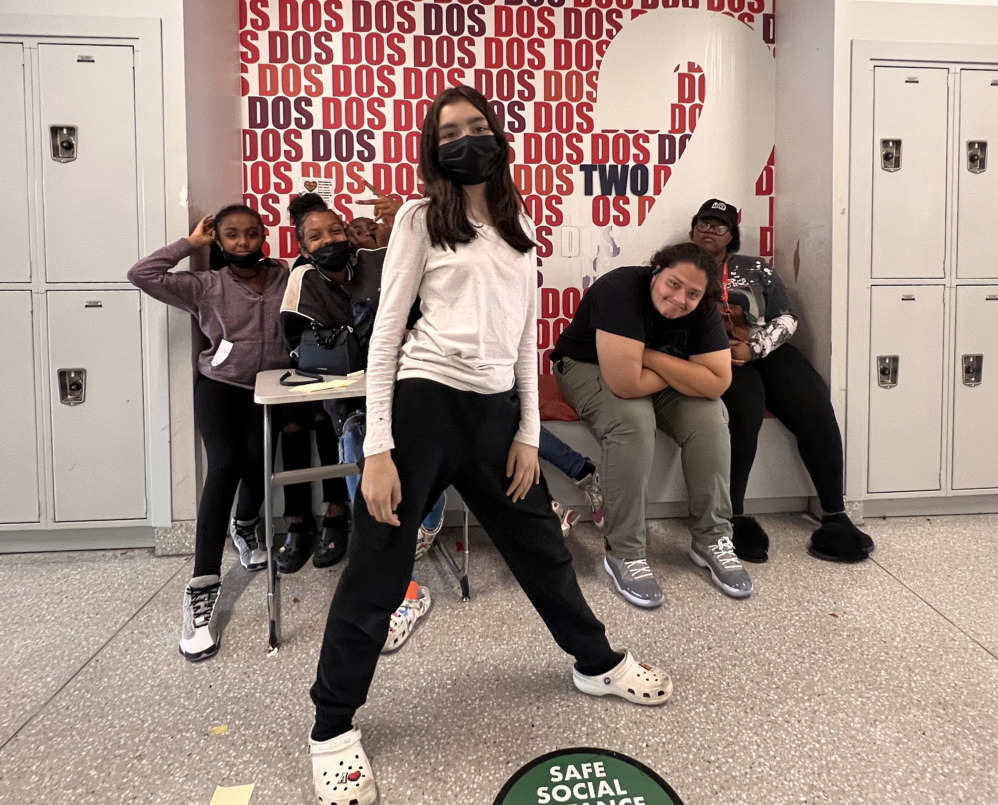

Courtesy of Kenvin Lacayo

“If we want our teachers to show up for our students, we also need to show up for our teachers in that way … More autonomy, more support, more professional development,” said Lacayo, pictured here second from right.

Q: Given that, how can we support students now?

First and foremost: listen. Oftentimes we make decisions for students, not with them. We say all the time how amazing and how great they are, and then we don’t have them be a part of decision making.

Mental health support has to be a big part. You can just tell the levels of depression, anxiety and even in some cases PTSD. Whenever these conversations come up, people think a lot about data and numbers. Those things matter, but working in education, we’re working with people. The number one thing is relationships. So find a kid that’s around you, and just build a relationship with that kid. Let that kid know that you love them and that you’re there for them. That goes a long way.

As far as policy, at the school where I work we practice restorative justice. It’s very difficult. It takes a lot of patience. But it’s extremely powerful when done right. So I would be an advocate for having more restorative justice schools and having that become more central to what education is doing across the country.

Q: What about supporting school teachers and staff during this time?

There’s been a huge exodus of teachers and people working in education, and it’s because we’re not meeting their needs. If we want our teachers to show up for our students, we also need to show up for our teachers in that way … More autonomy, more support, more professional development. It’s one thing to listen. And then it’s another thing to actually take what you’re hearing from teachers and actually make an adjustment.

Q: Ninety-nine percent of middle schoolers where you work are students of color. The program you participated in after high school worked to increase the diversity of teaching staff. Why is that important?

As a kid in school, I didn’t have a lot of teachers that came from my background or really understood it. But anytime that anybody came close to that, I really clinged to them. I had a couple of teachers once I got into high school who were Black men, and those were my favorite teachers, the ones I felt like I could relate to the most, who I would speak to the most, who I respected the most. I stopped going to school for two entire years, but if I ever went I would make sure it was on an “A” day because that’s when I had their class.

There’s something to be said about having someone around who understands you. There’s a lot of things that go on, nuances about where you’re from that only somebody who’s actually from there could speak to.

I see myself in my students, so I’m not going to ever come to school or treat them a certain way, because it’s like, I’m treating a younger version of myself. When I say I love them, I genuinely love them. I genuinely want the best for them. And I see myself in them.

***

Jacob Gardenswartz is a journalist based in Washington, D.C. He’s covered the White House, Congress, health and disability policy and other topics for outlets including NBC News, The New Republic and Youth Today. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, he holds an MPA from the Fels Institute of Government.