When the College Board announced earlier this year that students would take its flagship SAT test exclusively online in the coming years, its leadership touted the move as a “student-friendly” win with a shorter test, faster turnaround for scores and, overall, a less stressful experience for students.

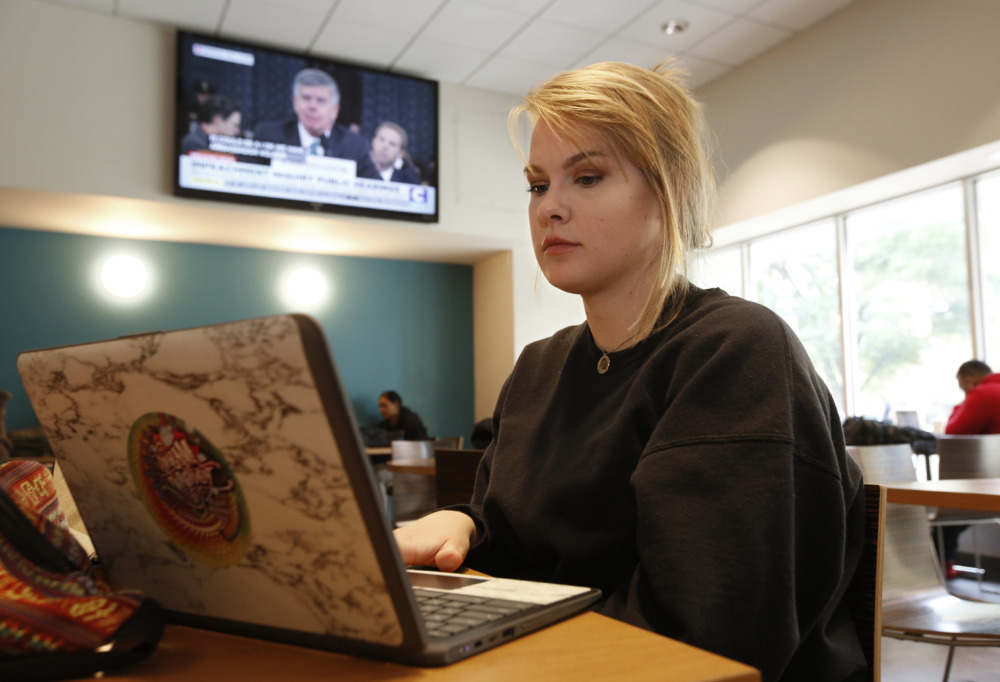

Kayla Helm-Queen

Kayla Helm-Queen is a 2016 college graduate with dyslexia who serves on the National Center for Learning Disabilities’ Young Adult Leadership Council.

But some young people who are neurodivergent or have learning disabilities, already concerned about what they say are structural biases in the existing test, warn that moving to an all-online SAT does little to alleviate their long-standing concerns about the test’s fairness and could even make the situation worse.

“Is going online better or worse? I mean, the analogy that came to my head was, is chewing tobacco or smoking a cigarette better or worse?” said Kayla Helm-Queen, a 2016 college graduate with dyslexia who serves on the National Center for Learning Disabilities’s Young Adult Leadership Council.

And with a growing number of universities extending pandemic-era policies that removed standardized testing requirements, some students and disability advocates see the digital shift as just another reason to skip the test altogether.

“It’s the same product,” Helm-Queen said of the new exam. “Some of the side effects are different, but it’s still harmful overall.”

Does a shorter test come with a cost?

The College Board has released few specifics about the new, digital test apart from the timeline of the rollout, with the computerized exam set to be implemented in the United States in 2024. The organization has said the new test will be significantly shorter than the current one, with just two sets of questions in each of the reading and writing and math sections. The online format also means scores will be returned more quickly to students, and calculators will be allowed on the entirety of the math section.

“Is going online better or worse? I mean, the analogy that came to my head was, is chewing tobacco or smoking a cigarette better or worse?”

Kayla Helm-Queen, member, National Center for Learning Disabilities Young Adult Leadership Council

“Shorter is better,” said Ruth Colker, a constitutional law professor and disability policy expert at the University of Ohio’s Moritz College of Law. But in order to pack the same level of assessment into the shorter time frame, the new, digital SAT will use a “multistage adaptive methodology.” That means that the second section of each topic will get easier or harder based on how students perform on the previous section.

Yet “those adaptive design frameworks are making assumptions about what you do or don’t know based on your previous answers,” Colker said. “For people who are neurologically atypical, they may not necessarily learn in the same even linear fashion of others.”

There’s little research into the impact of such approaches on students with learning disabilities. The SAT’s adoption of an adaptive model will mark one of the largest expansions of the process, with millions of students sitting for the test each year.

The College Board did not respond directly to questions about how the new test design could affect students with disabilities, but said in a statement that adaptive testing “has been used for large-scale digital standardized assessments for nearly 30 years.”

The ACT, too, has faced similar criticisms of bias and unfairness from disability groups, though students can take the ACT online or on paper.

Helm-Queen, whose dyslexia makes certain tasks like recalling multiplication tables more difficult, explained that she is able to to figure out complex problems but doesn’t always complete them in a “conventional” way. She worries that on a test like the new digital SAT, she might end up being pushed to an easier section after struggling with early questions, even though she has the capacity to succeed on a “harder” module. She’s also concerned about added anxiety the adaptive model could bring.

“I feel like I would get stressed out if I realized the test was getting easier because I wasn’t doing well,” Helm-Queen said.

An “uphill battle” for accommodations

Advocates and students with disabilities are also concerned that the transition to the new, digital test won’t address longstanding difficulties students with disabilities face getting the test-taking support they’re entitled to under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Extra time, more breaks, or access to a separate space to take the test are among the most common.

To get support, or accommodations, first, students must determine the types of assistance they need and are eligible to receive. Students must then apply, either through their high school or to the College Board directly, and provide documentation explaining why they require special assistance.

That process needs to change, advocates say. According to Marci Lerner Miller, a California attorney who’s argued several high-profile cases pertaining to standardized testing and students with disabilities, “Most people who try to get accommodations have difficulty doing it.”

Marci Lerner Miller

Attorney Marci Lerner Miller has argued several high-profile cases pertaining to standardized testing and students with disabilities.

One reason is that the types of evidence the College Board requests, such as psychological assessments, can cost upwards of $10,000. Students from wealthier families or with highly educated parents can usually find ways to navigate the bureaucratic system, Lerner Miller said, “but otherwise it is an uphill battle from the beginning.”

The computerized test will make certain types of accommodations more easily-accessible; students who are visually impaired, for example, will no longer need to request a special large-print paper exam, and can simply adjust the font size of the digital test with a few clicks. But otherwise the accommodations application process “is not expected to change,” the College Board said.

Advocates like Colker see that as a missed opportunity. With digital proctoring, students should be able to pause test-taking to enable more frequent breaks or receive extra time to take their exams with ease, she argued, adding that it’s a “a shame to waste the opportunity that becomes available when you go to a digital format.”

A world without admission tests

Standardized admission tests have faced allegations of bias and discrimination for decades, and concerns about whether the tests can accurately predict students’ success in college are nothing new. Over the past two decades, a growing number of schools stopped requiring standardized test scores in applications, with university leaders arguing the tests were not fully reflective of students’ abilities. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of universities across the country that did not require SAT or ACT scores for admission doubled, as testing centers were shuttered and students’ lives upended.

While schools such as MIT have reinstated testing requirements, over two-thirds of four-year colleges continued not to require tests for their incoming 2022 classes, despite the fact that most students have returned to the classroom and in-person administrations of standardized tests have resumed.

“You saw colleges successfully making admissions decisions for several years without tests. And so the question is, why then go back to them?”

College counselor Marybeth Kravets

And a small but growing number of schools have gone “test-blind,” stopping even considering SAT or ACT scores in admissions decisions. Last year, the University of California system agreed not to use standardized test scores in admissions or scholarship decisions for all its campuses, following a ruling in a lawsuit brought by students with disabilities who argued they lacked equal access to testing and accommodations in the wake of the pandemic.

Meanwhile, some preliminary research suggests that colleges that go test-optional could see an increase in the diversity of their admitted students. A 2021 study in the American Educational Research Journal found that test-optional admissions policies were associated with small increases in enrollment by low-income, female and Black, Latino and Native American students at schools with test-optional policies relative to colleges without test-optional policies.

Marybeth Kravets, a college counselor in Illinois with decades of experience helping neurodivergent students apply to college, says the pandemic may have been the nail in the coffin for standardized college admissions tests, especially for neurodivergent students and students with learning disabilities.

“You saw colleges successfully making admissions decisions for several years without tests,” she said. “And so the question is, ‘Why then go back to them?’”

Marley Brackett, a rising high school senior in San Diego, California, who has received accommodations for school tests in the past, opted not to take the SAT or ACT before she starts applying to schools this fall. The universities to which she’s applying do not require the tests, something she celebrated.

“They just seemed super painful,” Brackett said of the standardized tests.

She talked with her college counselor about how anxious the prospect of taking the new tests made her and the difficulty of navigating the accommodations process.

“We just kind of decided in the end it wasn’t worth it,” she said.

***

Jacob Gardenswartz is a journalist based in Washington, D.C. He’s covered the White House, Congress, health and disability policy, and other topics for outlets including NBC News, The American Independent, and YouthToday. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, he holds an MPA from the Fels Institute of Government.