ALBUQUERQUE — Michael B. Brown sits at a table inside of a visitors room at the Northeast New Mexico Detention Facility in Clayton. Tattoos, several of which he designed himself, cover the arms and neck of the six-foot-tall, blue-eyed, 44-year-old man who has lived behind bars for most of his life — since he was 16.

“I didn’t think I was going to live to see 25 years old,” says Michael. “I didn’t think I was going to survive this … but I’ve managed to maneuver my way through and after 27 years, here I am.”

Michael was tried as an adult and convicted of murder in the brutal deaths of Ed and Marie Brown, his grandparents, with whom he was living at the time. His grandfather was stabbed 58 times and his grandmother six.

A day after the slayings, Michael and two friends were arrested. Michael, who says he was hiding in his room when his grandparents were killed and did not take part in their murders, was sentenced to life plus 41 and a half years for two counts of first-degree murder, as well as tampering with evidence and the unlawful taking of a motor vehicle.

Michael is one of dozens of people in New Mexico who received what juvenile justice reformists call “de-facto life sentences” — sentences so long they will likely never be released — for crimes committed as minors. He is a vocal supporter of youth sentencing reforms that died in the state legislature earlier this year, part of a national movement to rehabilitate juvenile offenders and make them eligible for parole earlier.

Michael says he was a “drunk and stupid kid” at the time of his grandparents’ murders and regrets not taking action to stop them. He attributes his poor choices to immaturity and says he has since found meaning in life as a mentor to fellow inmates and at-risk youth.

In the years since Michael was sentenced, the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down life sentences without the possibility of parole for juvenile offenders based on neuroscientific evidence that adolescent brains are undeveloped compared to those of adults. But the court has not clarified how lower courts should view consecutive terms-of-year sentences.

The Supreme Court’s ruling and subsequent decisions have basically stated that “the federal courts are sick of dealing with this, and it’s up to the states to deal with this issue in enacting their own sentencing laws,” says Denali Wilson, an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of New Mexico and founding member of the New Mexico Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Youth.

Some states have taken it upon themselves to pass legislation mandating earlier parole eligibility for juvenile offenders, sometimes called “second chance” legislation. Advocates of these laws cite adolescent neuroscience and studies showing low recidivism rates among those sentenced as juveniles.

That ruling sparked a grassroots movement that eventually led to the introduction of New Mexico’s own ill-fated second chance bill.

“There are guys who had their entire lives hanging on this bill, and they had that yanked out from underneath them,” says Michael. “I don’t think anybody out there understands how that feels to have a light at the end of the tunnel and then have somebody slam the door.”

Many prosecutors and victims’ advocates oppose the proposed changes to New Mexico’s sentencing laws. They say forcing victims to testify at parole hearings earlier and more often would be traumatizing.

Some also question the scientific claims about adolescent brain development that form the basis of the youth sentencing reform movement, despite the Supreme Court’s acceptance of this evidence.

Barbara Romo, chief deputy district attorney for the 13th Judicial District, which includes Cibola, Sandoval and Valencia counties, is among those unpersuaded by the argument that adolescent brain chemistry should be a mitigating factor.

“If that was the cause, then every juvenile that’s an adolescent whose brain hasn’t been developed would be committing these atrocious crimes,” says Romo, who has spent a bulk of her career in military service and the legal field. “There’s something else going on in those individuals.”

How a cop’s son ended up in jail for the murder of his grandparents

Michael grew up in a law enforcement family and started rebelling by drinking heavily and running the streets at age 14, a few years after his mom and dad separated.

His father, a former officer with the Albuquerque Police Department and the Rio Rancho Department of Public Safety, worked long hours and was never around much, according to Michael and his younger sister, Shannon Fleeson.

“We spent a majority of the time with my grandparents,” says Shannon. “I was very, very close to them. I spent hours every night coloring with my grandpa and doing word searches with my grandma.”

On February 4, 1994, when Shannon was six and Michael was 16, she found their paternal grandparents stabbed to death in their home in the Albuquerque suburb of Rio Rancho, according to court documents.

Michael says that on the night of the murders, his grandmother had kicked him and his two friends out of the house for drinking. They eventually returned to the house and drank more.

Michael maintains that he did not lay hands on his grandparents. He says his two friends left his room, and then “there was screaming and yelling.”

Michael says he hid in his room with a pillow over his head while his grandparents were killed. He says that at the time he was heavily intoxicated and scared.

“I opened the door and there was blood all over the walls in the hallway,” Michael recalls. “At that moment I was instantly sober. Everything was so vivid and real.”

Gabriela Campos

Michael Brown wipes a tear away while talking about the 1994 murder of his grandparents in the visitation room at the Northeastern Correctional Facility in Clayton, N.M. on September 20, 2021.

“I freaked out and closed the door — I just froze,” he continues, breaking down in tears. “That’s one of the moments that I look back on with the most regret. I did nothing when I should have done something. They were always there for me and I betrayed them in the worst way.”

In New Mexico, a youth convicted of first-degree murder can receive one of two sentences: juvenile life without parole (a sentence that replaced the death penalty in 2009), which means an inmate must remain behind bars until they die; or life imprisonment, where offenders are eligible for parole after 30 years.

In Michael’s case, “he has to serve his whole life sentence, which is 30 years, then he would have to be paroled from that to start the 41 and a half years,” says Wilson, the ACLU attorney. “Literally nobody has any idea how long he will actually be in prison.”

One of Michael’s co-defendants, Bernadette Setser, confessed to police that she and their other friend, Jeremy Rose, stabbed the older couple. At trial, Michael was portrayed as the mastermind behind his grandparents’ murders. Later, Rose recanted, saying “no one made” him do it and that prosecutors coerced his false testimony in exchange for a softer sentence, according to court documents. In May 2020, Michael filed for a reduction of his sentence. The courts have yet to make a decision.

The slaying tore the family apart. Michael’s father didn’t speak to him for years. He eventually forgave his son after learning more about studies on adolescent brains, as well as observing Michael’s own efforts to better himself.

“It took my dad a long time to be able to come around to having a relationship with Michael … He was obviously very angry because it was his parents,” says Michael’s sister, Shannon. “They ended up having a conversation about what happened and my dad was able to forgive Michael. He saw all of the changes that Michael was making and that he’d become a different person that had matured and gotten educated.”

Michael and Shannon’s father declined Youth Today’s requests for an interview through his children.

Michael says it took him years to grasp the gravity of his situation. He had always assumed that he would never spend a day in jail due to his family’s connection to law enforcement.

“My dad and my sister always tell me that my grandparents would be proud of me now and who I’ve become. Sometimes it’s comforting … but part of me thinks, ‘Do I deserve that?’”

Michael credits education, connection for turnaround

Michael says he tried to put on a tough guy persona during the first five years of his prison stint. At age 17, he said he was stabbed in the neck with a screwdriver by a gang member.

“Prison back then was a very violent place. Everybody in here was two to three times my age and two to three times my size,” says Michael. “On top of that, I was a highly publicized figure in the murder. I was a little 16-year-old little white kid from a law enforcement family, and kids like that are a minority, so I was definitely behind the eight ball. It was scary.”

Michael eventually started taking classes offered to inmates. He earned his GED diploma and completed additional courses with the aim of one day becoming a social worker for vulnerable youth. He says he’s also tried to be a positive influence on other inmates, including teaching a safety workshop in the early days of the pandemic to try and mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, which hit New Mexico’s correctional facilities hard.

Jonathan Gooden met Michael around 2006 when Gooden was transferred to the same prison to serve out the remainder of his eight-year sentence for criminal residential burglary.

He describes Michael as someone who could bring together various factions within the prison, and even organized a series of softball games using a Gatorade bottle and a hacky sack.

“It was very unifying,” says Gooden, 41, who has since been released but remains close friends with Michael. “Mike definitely has that quality about him, regardless of petty prison politics, to get everybody to put that aside to just have fun.”

Michael, for his part, credits his wife, Jessica Brown, for helping him turn his life around. The two met through one of Michael’s former cellmates, who was dating Jessica’s best friend.

“It was like a brush fire that took off,” says Michael. “She slipped into my life like a whirlwind and stirred everything up and turned everything upside down. Nothing was ever the same after that in all the best ways.”

For Jessica, the connection was unexpected.

“I never in a million years thought that we would end up together-together,” she says. “It was just someone to talk to. Before I knew it, there was nothing that he didn’t know about me. He was my best friend and it just kind of went from there.”

Gabriela Campos

Shannon Fleeson, the sister of Michael Brown, tickles her son, Liam, 12, at their home in Santa Fe late September. “He makes everyone feel comfortable,” said Liam speaking of his uncle Michael.

Michael has since become a father figure to his wife’s three daughters and a supportive uncle to his sister’s two sons.

“My boys adore him and look up to him,” says Shannon, who says that her oldest son Liam, 12, wants to play drums in the school band because Michael is a drummer. Years ago, Michael, who’s also a guitarist and visual artist, and a few of his fellow inmates performed a pop-punk set at a family banquet at the prison under the band name Sack Lunch.

“Whenever I can’t get through to (Liam), I put him on the phone with Michael and I can tell my son is listening to what he’s saying,” Shannon says. “When they hang up the phone, my son’s attitude and outlook have changed.”

Liam says his uncle talks to him about school and helps him get along with his brother.

“He makes everyone feel comfortable,” Liam says. “I love him and wish he was home.”

A reform movement gains steam

There are approximately 75 people in New Mexico serving sentences of more than 15 years for crimes committed when they were minors, according to the New Mexico Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. Close to 40, including Michael, are serving sentences of 30 years or more.

Since Michael’s sentencing, calls to ban life without parole or lengthy sentences for juveniles, even those who commit serious crimes such as murder, have gained momentum.

In a 2012 joint decision in Miller v. Alabama and Jackson v. Hobbs, the Supreme Court prohibited mandatory life without parole for juvenile offenders, even in homicide cases.

Writing for the majority, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that adolescence is marked by “transient rashness, proclivity for risk, and inability to assess consequences” and that mandatory life without parole violates the 8th Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishments.

In the years that followed, a number of state supreme courts extended the decision to apply to consecutive terms-of-year sentences that they said effectively amounted to life without parole.

Some state legislatures also took up the issue by passing second chance legislation mandating earlier parole eligibility for juvenile offenders. This year, Maryland banned juvenile life without parole, and Michigan and Wisconsin legislatures are discussing similar reforms.

The issue came to a head in New Mexico in 2018 when that state’s Supreme Court upheld the sentence of Joel Ira, who is serving a 91-and-a-half year prison term for the violent sexual abuse of a younger child when he was 14 and 15 years old.

Although the court upheld Ira’s sentence, the judges invited the legislature to take up the issue, pointing out that a number of other states had already done so.

Gabriela Campos

Denali Wilson, attorney at the ACLU of New Mexico and founding member of the New Mexico Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Youth sits in the courtyard of the ACLU in Albuquerque.

“The New Mexico Legislature is at liberty to enact legislation providing juveniles sentenced to lengthy terms-of-years sentences with a shorter period of time to become eligible for parole eligibility hearing,” the decision reads. “Although we consider Ira’s opportunity to obtain release when he is 62 years old constitutionally meaningful, albeit the outer limit, we do not intend to discourage the legislature from adopting a shorter time period as have many other jurisdictions.”

The following year, Wilson, who was still a law student at the University of New Mexico’s main campus in Albuquerque, helped found the Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Youth.

Since then, the group has grown to 100 members and allies, including some public defenders, and includes family members of people serving long sentences for crimes committed when they were teenagers. They went to work pushing for a second chance bill, and received a crash course on the legislative process.

The fruits of their efforts was Senate Bill 247, co-sponsored by Sen. Antoinette Sedillo Lopez (D-Bernalillo) and Rep. Dayan Hochman-Vigil (D-Bernalillo).

Originally, the bill would have made juvenile offenders eligible for parole after 10 years. That threshold was increased to 15 years in the face of vocal opposition.

“SB 247 was the most grassroots legislative campaign that there has probably been in New Mexico,” says Wilson. “It was just us and me as a baby lawyer not knowing anything about lobbying and trying to show up because we couldn’t get a New Mexico organization to commit to this issue.”

SB 247 passed the state Senate with bipartisan support. But it was never brought up for a vote in the House and died with the end of the legislative session.

“The formula shouldn’t be about retribution, but about rehabilitation,” says Sedillo Lopez, a former law professor and a member of the New Mexico State Senate since 2019. “If you have the possibility of rehabilitation and giving these children hope, I think that’s good public policy.”

Though many members of the New Mexico District Attorney’s Association opposed the second chance measure, Mary Carmack-Altwies, district attorney for the First Judicial District covering Santa Fe, Los Alamos, and Rio Arriba counties, backed the legislation.

She emphasized that the proposed legislation didn’t allow for automatic release, but rather gave those sentenced as youth an opportunity for review by a parole board.

“We simply do not know what a 15-year-old will be like by the time they are 30,” wrote Carmack-Altwies in a letter to the New Mexico House of Representatives. “SB 247 creates the opportunity for us to take this much-needed second look at who a young person has grown to become instead of just focusing on the wrongs that they did.”

As SB 247 made its way through the New Mexico Senate and into the House, supporters relied on neuroscientific evidence from local and national experts.

One such expert was Tina Zottoli, a licensed clinical psychologist in New York and an assistant professor in the department of psychology at Montclair State University in New Jersey.

Gabriela Campos

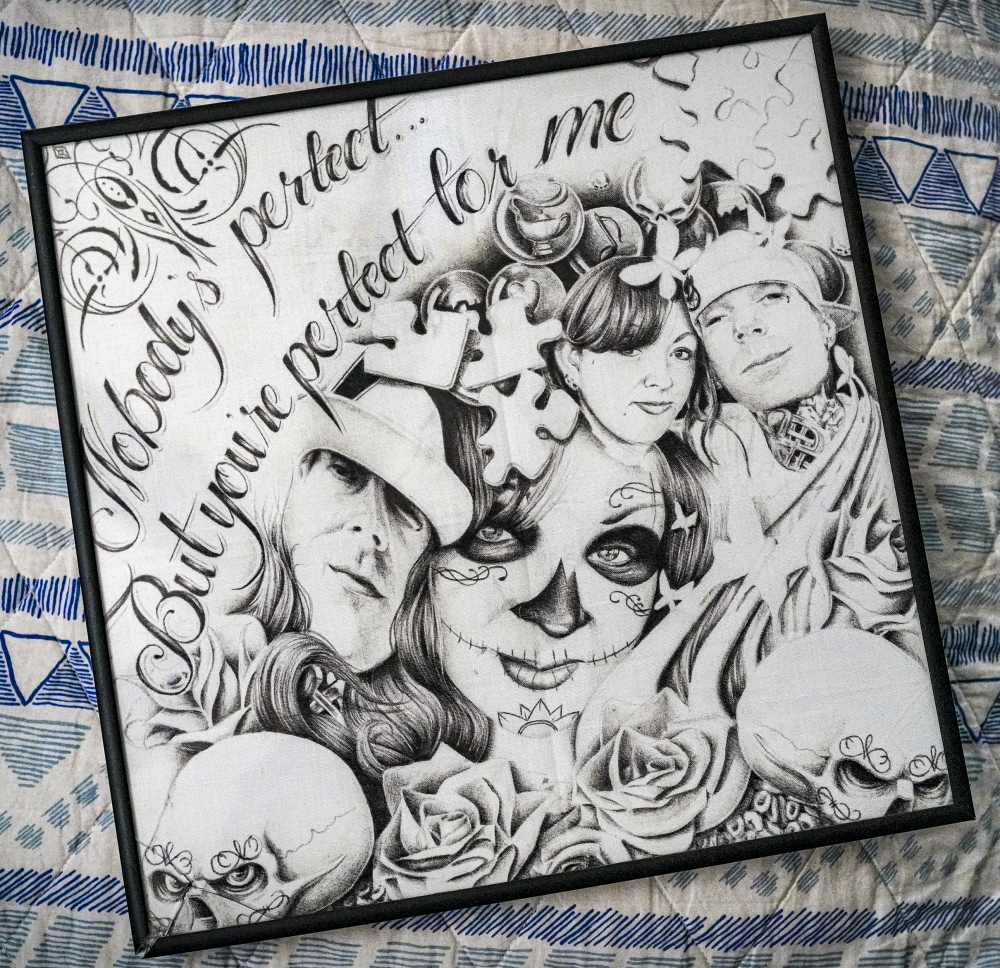

A pen and ink portrait drawing that Michael Brown made for his wife Jessica Brown featuring a portrait of the couple along with their favorite phrase, “Nobody’s perfect.”

Zottoli co-authored a 2020 study that found a recidivism rate of just 1 percent among 269 people who were sentenced to life as juveniles and subsequently released. The study concluded that many people “age out” of criminal behavior as they grow up.

“As you reach your early 20s and into your mid 20s, there’s a gradual catching up of the prefrontal regulatory systems, and you see a calming down of that impulsivity, short-sighted, risk-seeking behavior,” says Zottoli.

Zottoli says that an individual’s brain development can be complicated for those who grow up in unstable, impoverished or challenging home environments.

“Our brain is developing patterns based upon the feedback we get in our environment,” Zottoli says. “Of course, it’s not just the brain. Psychosocial development is so important in addition to cognitive development.”

Michael thinks his age and brain chemistry played a role in his actions 27 years ago.

“Thinking about it with a 44-year-old man’s brain is different than thinking of it with a 16-year-old brain that was trashed from a half a bottle of gin and a 12 pack and a half of beer in me,” he says. “I certainly would have done things differently now.”

‘What it is like to have a family member murdered’

Many victims and prosecutors came out against New Mexico’s proposed second chance bill.

In the face of sympathetic portraits of reformed juvenile offenders, they offered their own emotionally-charged stories of tragedy, loss and terror.

The National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Murderers circulated an online petition against SB 247 that focused on Nathaniel Jouett, who killed two people and injured four others during a mass shooting inside of the Clovis-Carver Public Library in Clovis, New Mexico in August 2017. The Chicago-area group publishes victims’ rights materials and examples of violent crimes committed by youth on the website teenkillers.org.

The group opposes wholesale legislative changes “unless they protect public safety from psychopaths and violations of victims’ rights,” says President Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, whose sister, brother-in-law, and the couple’s baby were killed by a minor.

“Until someone has walked a mile in our shoes, no one can even come close to understanding what it is like to have a family member murdered,” she says.

She emphasizes that the rights of victims should be considered, especially the traumatizing potential of parole hearings that may come earlier and more often under the proposed reforms.

Some critics of the reform movement have questioned the conclusions drawn from adolescent brain studies, while some judges have pushed back on certain defense arguments rooted in neuroscience.

New Mexico Chief Justice Judith Nakamura, writing a separate opinion upholding the lengthy sentence of Joel Ira, concluded that a distinction must be drawn between a juvenile who commits a single, impulsive act and someone like Ira who carried out repeated, violent attacks over a period of two years. The opinion included graphic descriptions of Ira’s abuse of the child, underscoring the kind of trauma victims could be forced to relive in parole hearings.

Romo, a former lead attorney for the New Mexico Victims’ Rights Project, said the studies on immature brains support correlation, but not causation, when it comes to criminal behavior.

Gabriela Campos

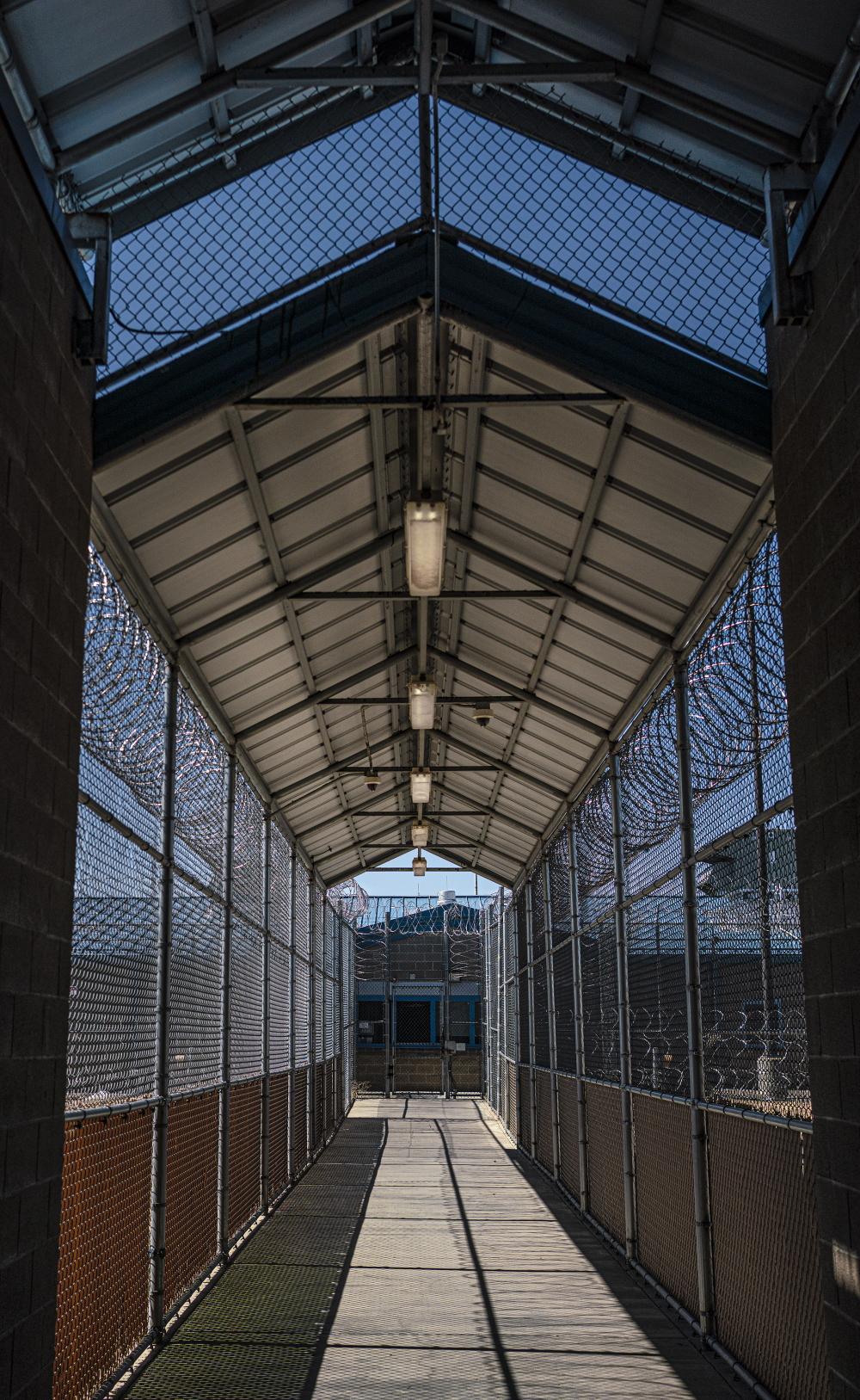

The outdoor hallway leading from the administrative building to the visitation room at The Northeast New Mexico Detention Facility where Michael Brown is serving his sentence in Clayton, N.M.

“Without that link, you’re making a dangerous assumption that these now adults, who were juveniles at the time that their brain or whatever personality thing caused them to commit these crimes, have changed,” she says. “Who’s going to make that determination? The parole board? Based on what?”

Romo also thinks SB 247 went too far in decreasing the amount of time before a juvenile offender would have been eligible for parole. She advocates for mandatory parole eligibility after 30 years, which is the state’s mandatory minimum for first-degree homicide.

Some players in the legal system have changed their minds as the national movement for sentencing reform gains momentum.

Preston Shipp, a senior policy counsel at The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, was a prosecutor in Tennessee until 2009. He says back then, he never would’ve believed that youth convicted of violent crimes were worthy of a second chance.

“I dehumanized those people,” says Shipp, who began to change his mind while teaching a law class at a college prison program. He says the case of Cyntoia Brown, a 16-year-old trafficking victim who received a life sentence for killing a man who had picked her up for sex, was especially eye-opening.

With time, he says he realized “justice isn’t some kind of zero sum game.”

“I can want both sides to heal and to move forward to have a better future,” Shipp says. “I think that’s what justice requires of us. I didn’t used to think that — all I was doing was arguing that people needed to go away for decades at a time.”

Bipartisan sentencing reforms a ‘casualty of political drama’

In the end, heated arguments at the tail end of New Mexico’s legislative session over unrelated issues devolved into name calling and character attacks, and many pieces of legislation, including the second chance bill, never made it to a final vote.

“It was a casualty of political drama more than anything, not the substance of the bill or the important issue of age-appropriate sentencing for kids,” says Wilson. “New Mexico has some reckoning to do, and it needs to be a top priority for our state.”

She said the Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Youth recently resumed regular meetings in an effort to get the legislation introduced in the 2022 session.

In New Mexico, the legislature meets for 30 days in even-numbered years to focus on the state budget and for 60 days in odd-numbered years to consider sweeping policy changes. As such, there’s a chance that a second chance bill won’t be reintroduced until the 2023 legislative assembly.

Although New Mexico’s bill didn’t make it to the governor’s desk, Michael says he will continue working for positive change, despite the real chance that he’ll spend most of his life locked up.

“It’s just warehousing and punishment,” he says of today’s prison system for young offenders. “You either take it upon yourself to fight to grow into a good man, or you absorb this culture. Some have given up and are basically waiting to die.”