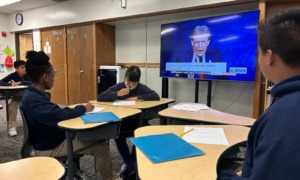

Elaine Thompson/AP

Leroy Pascubillo touches hands with his daughter, who was born addicted to heroin and placed with a foster family at birth, May 10, 2021, in Seattle.

SEATTLE (AP) — Leroy Pascubillo missed his daughter’s first step, her first word and countless other precious milestones. After being born addicted to heroin, she had been placed with a foster family, and he anxiously counted the days between their visits as he tried to regain custody. But because of the pandemic, the visits dwindled and went virtual, and all he could do was watch his daughter — too young to engage via computer — try to crawl through the screen.

They are among thousands of families across the country whose reunifications have been snarled in the foster care system as courts delayed cases, went virtual or temporarily shut down, according to an Associated Press analysis of child welfare data from 34 states.

The decrease in children leaving foster care means families are lingering longer in a system intended to be temporary, as critical services were shuttered or limited. Vulnerable families are suffering long-term and perhaps irreversible damage, experts say, which could leave parents with weakened bonds with their children.

The AP’s analysis found at least 8,700 fewer reunifications during the early months of the pandemic compared with the March-to-December period the year before — a decrease of 16%. Adoptions, too, dropped — by 23%, according to the analysis. Overall, at least 22,600 fewer children left foster care compared with 2019.

“Everybody needed extra help, and nobody was getting extra help,” said Shawn Powell, a Parents for Parents advocacy program coordinator in King County, Washington.

For months, King County, like many parts of the country, suspended nearly all hearings except emergency orders, which led to prioritizing child removals — sparked by child welfare reports or other red flags — over family reunifications. Adoptions slowed to a trickle. Services needed for reunification — psychiatric evaluations, random drug testing, group therapy, mental health counseling, housing assistance, and the public transportation to access these services — also were limited.

For foster care children, even doctor’s appointments must be approved by a judge, and frustrated lawyers say matters as routine as that were affected.

During the period examined in AP’s analysis, the total foster care population dropped 2% overall — likely a result of the significant decrease in child abuse and neglect reports, where the process to remove a child from a home typically begins.

National data show that the average stay in foster care is about 20 months, which means the children most affected during the early months of the pandemic were those in the foster care system long before the pandemic.

Those in foster care are disproportionately children of color and from poor families, national data also show. Those groups tend to have more contact with social service agencies that are mandated to report potential abuse and neglect, which means the pandemic has amplified not just the challenges of poor parenting but of parenting while poor.

“The systemic problems around racism and poverty in COVID and how people are treated in the child welfare system may be compounding,” said Sharon Vandivere of the national think tank group Child Trends, who noted that longer stays in foster care are inherently traumatic and make reunifications less likely. “It was bad before, and it’s probably made it even worse.”

Ted S. Warren/AP

“D.Y.,” a teenager who is currently living in a foster-care group home, is currently suing the Washington state Department of Children, Youth and Families, alleging that the state has provided inadequate care after bouncing him through more than 50 placements before the COVID-19 pandemic.

For D.Y., a Black teenager living at a Seattle-area group home, the pandemic has magnified the loneliness and isolation of being in the care of child protective services. He’s been out of his mother’s custody since 2016, after an abuse report found she physically disciplined her children. He had visits with her in the years following, and lawyers expected his mom would regain custody and D.Y. could go home in the fall of 2020. Then the pandemic hit and rocked his case and life.

Because of new COVID-19 protocols and staffing shortages, already-limited privileges at the institutional group home were scaled back or revoked. In-person visits with his mom ended. Group activities all but disappeared. Inside, he resented wearing a mask and washing his hands constantly. With each exposure scare in the living facility, he and others had to quarantine.

When he resumed in-person school, he hoped officials would find it safe to see his mom again, too — but that didn’t happen for months. He watched helplessly as his sister – who was placed with relatives and had a case further along in the system when the pandemic began – was returned home to their mom last summer. D.Y. was happy for them, but he wants the same: to taste his mom’s cooking, to make eggs in his own kitchen, to sit on the couch with his family with no masks.

“I still want her to baby me,” the 13-year-old boy said of his mother, who declined to comment for this story while the cases of D.Y. and her third child remain active. “I can tell she has high faith of when I’ll come home. I don’t know if it’s going to happen anymore.”

The AP is not naming D.Y., instead referring to him by the initials used in his lawsuit against the Washington State Department of Children, Youth and Families. The lawsuit accuses the state of providing inadequate care as D.Y. was bounced through 50 placements before the pandemic, some days housing him in a motel or the agency’s office building. The state declined to comment on his case and lawsuit.

But Frank Ordway, chief of staff at the state’s child welfare agency, blamed the court system’s closures for the drop in reunifications and implored those that still haven’t fully reopened to prioritize cases like D.Y.’s.

“When those systems aren’t working, those families and those children are left in limbo,” Ordway said. “Our job as an agency is to help keep those families together and to get them together. Not being able to do so because of the pandemic was a wrenching experience.”

King County Superior Court Commissioner Nicole Wagner, a presiding judge in the family court system, said court staff, attorneys, social workers and counselors did their best, but that no one knew how to address unprecedented issues in the pandemic. For example, she said, she wanted in-person visits for children but couldn’t order social workers with underlying conditions to monitor them when required by law.

Wagner said she hopes lessons from the pandemic will help redefine how the system supports already struggling families in the process of reunification.

“It’s scary, it’s overwhelming, it’s frightening. And it’s about the most important things in your life: your children,” Wagner said. “There’s no doubt in my mind that the pandemic absolutely, 100% has disproportionately impacted the more vulnerable populations.”

Illinois was the only state that kept apace on its foster care exits. Others in AP’s analysis acknowledged a significant drop but said that each foster care case has unique circumstances beneath the numbers.

Many states, for example, extended its support to those on the cusp of aging out of state care during the pandemic. This policy change effectively protected foster care youths from being kicked out of their living arrangements if they still needed a place to stay, but it also affected the number of foster care exits.

Connecticut — which had one of the largest drops in exits, at 36% — waited until May 2021 to fully return to in-person visits, which serve as a key metric to judge whether parents are prepared to regain care and custody of their children.

The state “never stopped serving children and families, and we found that conducting some of our work virtually is both more efficient and, in some cases, preferred by our clients,” a Connecticut Department of Children and Families spokesman said in a statement.

Leroy Pascubillo, now 51, had used drugs over the course of four decades, but said he started working toward sobriety immediately after his daughter’s birth in February 2019.

The court put him in the only drug rehab center in the Seattle area that allows children to stay on site with their fathers. He had a few in-person visits with his daughter each week, and he was told that if he got through the initial stages of the program, she could join him there in March 2020 while he completed treatment. The pandemic upended that plan.

“You start building that relationship, and then it’s taken away and you try to start it all over again,” he said. All the more painful was that he knew his daughter, now 2, also had no contact with her mother. Pascubillo said she hasn’t participated in the custody case, and she couldn’t be reached by the AP.

Once courts began to hear existing cases again, Pascubillo was able to reunite with his daughter, complete rehab and land a Seattle apartment with the help of state and nonprofit services. He wants to work as a parent advocate to help other fathers find their way back to their kids. He still weeps over the time he’s lost and the four-month delay in reuniting with his daughter.

“It felt like 40 years. I figured she would have forgotten me. But as soon as I looked at her and sang ‘baby, baby, baby,’ she started kicking like she was in the womb,” Pascubillo said. “We have this bond.”

Fassett reported from Santa Cruz, California, and is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.