Photo by Infrogmation

Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office building in Harvey, La.

Who shot Tre’mall McGee?

It is a question that has been posed to every level of law enforcement in Louisiana. From the city of Westwego, where the 14-year-old boy was shot in the back, to the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office whose deputies initiated the chase that led to his shooting, to the Louisiana State Police who are responsible for investigating police shootings.

“I even called the FBI,” said Tre’mall’s mother Tiffany McGee, 36. “But I still haven’t gotten any answers.”

The odyssey she went on to find out what happened to her son is one part Cajun mystery, one part disorienting Kafkaesque journey in which she has a son who has been shot but no one pulled the trigger.

Courtesy of Tiffany McGee

Tre’mall McGee

No one has identified which member of law enforcement shot the boy in his back as he lay prone after falling to the ground when commanded by police.

Monroe Dillon, a spokesman for the Louisiana State Police, said his agency does not have an open investigation into Tre’mall’s shooting, an indication that the shooting was never reported.

Tre’mall had a hole in his arm from the bullet that is healing into a scar. He has documentation from the hospital on how to treat a gunshot. But to this day, months later, he and his mother have no idea who pulled the trigger that sent the bullet tearing through his back, out his armpit and then back through his arm. But mother and son know it was someone with a badge.

“We have a situation where law enforcement is involved in the cover-up of the shooting of a child,” said Ronald Haley Jr., who is representing Tre’mall and his mother.

Presumably, McGee said, that very same officer who shot her son is still going out on patrol during his shift, armed with a gun, capable of shooting someone else for lying on the ground and doing what he was told. She said she has called law enforcement at every level of government and she still hasn’t gotten any answers.

“You all wouldn’t be giving me the runaround like this if you all weren’t trying to hide something,” McGee said.

The Louisiana State Police, the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office and the Westwego Police Department have all declined to comment on this story. Jefferson Parish President Cynthia Lee Sheng also declined to comment. A spokesman thanked a reporter for bringing this issue to light but said it sounded like it was a sheriff’s office issue.

The chase

Courtesy of Ron Haley

Ron Haley

According to Tre’mall and another teenager in the car, he was picked up in the early evening of March 20. Tre’mall and three other teenagers were driving around and hanging out. He says he had no idea the car was stolen. Only the driver knew that.

When the driver noticed a squad car from the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office behind him, he panicked. He started speeding, trying to get away. Inside the car it was pandemonium. Tre’mall and his friends didn’t understand what was going on and were yelling at him to slow down and pull over. The driver didn’t listen.

Other police cars joined the chase. Eventually, the driver screeched to a halt in Westwego, a New Orleans suburb. The driver jumped out of his seat and ran in one direction. The other boys jumped out and headed in the opposite direction.

Tre’mall was in the back seat. He had never been in trouble before so he had no idea what was going on. He saw the other boys running, so he started running, too, he said.

He didn’t make it far before officers commanded him to get down. They had their guns drawn already. He fell to the ground immediately on his stomach. The officers shouted commands to put his hands behind his back. Tre’mall complied.

He didn’t make it far before officers commanded him to get down. They had their guns drawn already. He fell to the ground immediately on his stomach. The officers shouted commands to put his hands behind his back. Tre’mall complied.

Meanwhile another passenger, 18, had been caught at a nearby fence. Another had successfully hidden himself underneath an elevated shed in a yard. One officer stood over Tre’mall and screamed.

“Tell me where your partner is at or I’m going to kill you,” he shouted.

Tre’mall didn’t answer his question. He was scared.

“Tell me where your partner is at or I’m going to shoot you,” the officer shouted again.

Again, Tre’mall lay silent.

And that’s when the officer squeezed the trigger.

Mother decides to go on ‘little detective mission’

McGee was too discombobulated to even process what she had just heard. She held the phone in her hand frozen for a moment. She had had a pleasant evening with her sister-in-law and the last thing she could have expected was this phone call. She asked the voice on the phone, a nurse from the University Medical Center in New Orleans, to repeat what she had just said. “Tre’mall McGee has just been shot,” the voice repeated. “We need some information.”

Courtesy of Tiffany McGee

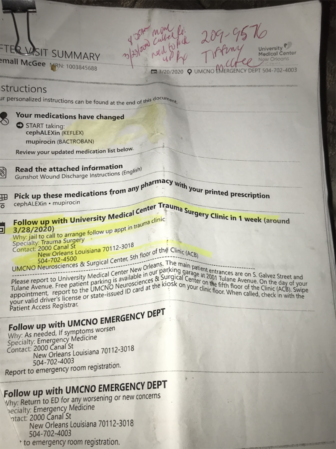

Tre’mall McGee’s gunshot wound discharge instructions from University Medical Center in New Orleans.

McGee gathered herself and told the nurse: “That’s my son. He is a minor. I am on my way.”

She grabbed her keys and dashed to the car. She lives on the west side of the city. The hospital is on the east side, a good 20-minute car ride away. McGee said she has never run so many red lights in her life as she did that night in a panic to get to her son. When she got to the hospital she was hysterical, she says.

McGee explained to security that her son had been shot and she needed to see him. The staff rushed her through the waiting room and to the nurse who had called her. As she led her to the back to fill out paperwork, the nurse explained what had happened. ”They dropped him off tonight,” McGee remembers her saying. She never explained who “they” was.

The nurse led her to a doctor and two police officers, a white detective and a black deputy. The doctor explained the trajectory of the bullet but didn’t say where it came from. The detectives didn’t say much, McGee said.

“They explained nothing, they said nothing. They left the impression like they were investigating the shooting of my son,” she said. “They didn’t … even try to tell me the truth. They didn’t tell me the truth at all. They left me with the impression that he got shot on the street and they were trying to figure out who shot him.”

McGee said nobody told her Tre’mall had been delivered to the hospital by paramedics who had been summoned by the police. She tried to see him at the hospital but the police told her she couldn’t.

“We can’t allow you to see your son right now,” she recalled them telling her. “He’s in police custody.”

After she left the hospital she reached out to the father of another boy who had been in the car. That father had no idea where his son was, McGee said.

“We went on our own little detective mission,” she said. “That’s when we found what was going on — what was really going on.”

McGee uses an app that tracks her son. She and the father drove to where the phone was pinging. It led them to the Westwego Police Department.

“I was like, why is my son’s phone in the back of this police department,” she wondered.

She thought maybe her son had dropped it when he was running from the police or that someone found it and turned it in to the police. She approached an officer coming out of the building and asked him if he could go in and check on Tre’mall’s phone.

Back to the hospital

At first the officer confused her son with a 14-year-old who was killed that same night and offered her his condolences. McGee corrected him and explained that her son was alive and recovering at the hospital. That’s when she found out what really happened, she said.

“Oh, so your son was shot by the officer tonight,” she recalls the officer telling her.

McGee heard the rest of the story after she took Tre’mall home the next day. Someone from Rivarde Juvenile Detention Center called her and told her to pick her son up. His gunshot wound had opened back up. She said they gave him napkins to stuff into the bandages. A spokeswoman declined to comment.

“I couldn’t hug him because his arm was hurt,” she said. “He seemed so sad; I’ve never seen my son so hurt like that. He said, ‘I’m hurting, I’m hurting bad.’”

McGee took Tre’mall back to the hospital and said she lectured them about the shoddy job they did on her son: “You can’t treat everybody like they’re criminals — he is not. You don’t know what he’s been through. My son wouldn’t have opened up if you sewed him up right in the first place.”

After they patched Tre’mall up properly, the staff gave her an after-visit summary. It suggests that the patient read the attached information. It recommends that Tre’mall take cephalexin, an antibiotic, and mupirocin, an antibiotic that stop bacterial growth on skin.

One part reads “Gunshot Wound Discharge Instructions.” At the bottom of the page it suggests “a follow up with trauma surgery clinic center in 1 week around 3/28. Why: jail to call to arrange follow up appt in trauma clinic.”

McGee shudders when she thinks about how easily things could have been different. Had the gunshot been a few inches in another direction her son could be paralyzed or dead. She is concerned that the officer who shot her son is still out there working.

“Still with a job, still working, still out there able to tote a gun and still able to point it at someone else’s child,” she said. “I don’t think that’s right. That’s what angers me inside, and I just keep that down there. They need to shut that Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office down and rebuild it all from bottom to top again.”

‘Justifies the distrust’

Tiffany McGee’s mission to seek acknowledgement and then justice for her son is happening against the backdrop of another controversial shooting that the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office has offered little information about. Modesto Reyes, 35, was shot and killed by Jefferson Parish deputies on May 27 after a short chase. One deputy used a stun gun on Reyes, another used a gun, with fatal results. The sheriff’s office has released eight seconds of stun gun cam video, but offered no statements.

“If we look at the shooting of Modesto Reyes and the protests of the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office that are growing amidst others around the country after the killing of George Floyd, it shows they have a culture problem within the department with how they treat black folks,” said Haley, who is also representing Reyes’ family.

What happened to Tiffany and Tre’mall illustrates why there is so much anger and contempt for the sheriff’s office in the community, he said.

“This cover-up justifies the distrust that the families of those brutalized by the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Department have of the office,” Haley said. “If they would go so far as to cover up the shooting of a child, there is no question that they would possibly cover up other abuse of power by their officers.”

Pointing to what he characterizes as law enforcement’s bizarre reluctance to even acknowledge that the shooting happened, Haley said he wants the Louisiana Attorney General’s Office to open an investigation into who shot Tre’mall McGee immediately.

“Normally, even if they’re trying to cover up, at least they’ll get up and say the shooting was justified — in most cases you will hear the argument from law enforcement, their unions, or whatever investigative body is in charge of the investigation,” he said. “They will at least try to justify an officer shooting. They’re so brazen in Jefferson Parish they won’t even acknowledge that a shooting happened.”

Jefferson Parish President Lee Sheng is the daughter of the wildly popular, larger-than-life former Jefferson County Sheriff Harry Lee. He summed up the scope of the sheriff’s office in an interview with NPR in 2006:

“The sheriff of [Jefferson Parish] is the closest thing there is to being a king in the U.S. I have no unions, I don’t have civil service, I hire and fire at will. I don’t have to go to council and propose a budget. I approve the budget. I’m the head of the law-enforcement district, and the law-enforcement district only has one vote, which is me,” he said.

That story notes that the sheriffs in Louisiana operate with virtually no oversight. That law has not changed.