VIDEOGRAPHER: KATHERINE WEBB-HELM

“You could say I’m an expert at being stuck at home,” said Jacob Frazier, a 17-year-old high school senior who is abiding by Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey’s April 3 shelter-in-place order to slow the spread of COVID-19.

This isn’t the first time Frazier has been in isolation. His first quarantine began in November after a bad car accident. His girlfriend had performed in an on-campus musical, and he stayed “a little too late” after the curtain to chat with her and friends. At 2 a.m. on the dark highway close to his home outside Gadsden, he fell asleep at the wheel. As the car veered off road, he woke and swerved to correct its path. The car flipped multiple times. His neck was broken in three places.

For the next few months, Frazier recovered wearing a restrictive halo. Just when he returned to a normal schedule of his Advanced Placement classes and theater rehearsals, Alabama schools closed because of coronavirus.

Now he’s home with his mother, who drives 90 minutes to work in Georgia where she’s a social worker for a prison system, and his cousin, who works for a nursing home. To help with bills, he worked as a tutor at Gadsden State Community College, but that job is on hold.

Just like teenagers across Alabama and the nation, Frazier is trying to finish a school year without the grounding of his usual routine — in the middle of a global public health crisis.

While it’s rare for young people to have life-threatening reactions to coronavirus, that doesn’t mean they aren’t struggling through the disruptions in daily life. Being away from the routine and safety of school, extracurriculars, work and friends can be dangerous for young people’s mental and physical well-being. That’s true for all kids, according to youth advocates, but especially so for more vulnerable populations. For kids in homes where resources are scarce, caretakers are negligent or violence is common, schools are often lifesaving resources.

Depending on a kid’s circumstances, those resources look very different. An Alabama Department of Human Resources spokesperson said neglect and abuse reports were down 14% this March compared to last year. The decrease is similar to the annual summer decline when students are out of school and away from educators, coaches and counselors who are often the first to suspect abuse.

Advocates for juvenile offenders said this break from structure or the inability to connect with the community during a period of recovery can be detrimental to keeping a kid out of trouble. And educators said the transition to a virtual classroom is challenging for basic instruction but devastating for staying emotionally connected with the kids who need it most.

More important than grammar

“I’m worried for the kids who are having a hard time right now,” Frazier said. The lessons he learned from the accident are carrying him through this second isolation. Part of that is letting go of expectations.

This time of year usually marks year-end celebrations and summer preparations for teenagers.

With regular traditions like prom and graduation ceremonies in limbo, teenagers aren’t sure what to expect for the coming months. Studies show the transition after high school is often the most stressful time in a young person’s life, and for those transitioning during a global pandemic, the added worry of whether the future they’re planning for is even possible can be overwhelming. Plus, there’s still schoolwork.

“I know how difficult it is to try and keep up with schoolwork at a consistent classroom pace while not being in the classroom,” Frazier said.

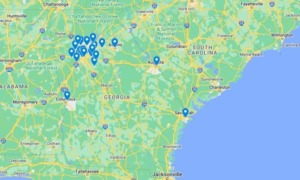

The transition to virtual classrooms wasn’t easy for many students or teachers who had little time to prepare. One of the biggest challenges continues to be access to the necessary tools for distance learning — a computer and the internet. In Alabama, internet scarcity is as high as 30% in some counties. But a recent report showed availability doesn’t necessarily mean individual access. Families living in poverty may not have a computer for kids to use at home, or if the school sends home a laptop, families may not be able to afford internet.

In response to coronavirus, companies have offered free broadband, school systems have created their own rural hot spots and some districts, like Huntsville City Schools, are broadcasting hours of instruction on TV.

Virtual classrooms only work, though, when students have time to participate, educators said. While some child care centers across the state remain open for essential workers, those places are for young kids. With varying situations for parents who either work from home or leave for their essential jobs, child care options are limited. Fear of spreading the virus has led families who usually rely on extended family or neighbors to leave kids at home with their older siblings.

That means teenagers are taking on demanding responsibilities. One Alabama family said a preteen was babysitting two kids under 3 while the parents were at work. Another said a grandmother babysat before the pandemic but was now too worried about asymptomatic spread of the virus to keep the kids so child care fell to a 15-year-old. Another family with six children said older kids helped their stay-at-home mom manage household tasks.

Even when students are plugged into the classroom, that doesn’t mean teachers can still connect in the same way. One of Frazier’s teachers, Heather Ross, an instructor of literature and composition at Gadsden City High School, said it’s been “heartbreaking” to not see students daily.

Her students were already using an online system so the technical shift wasn’t as challenging, but staying in tune with a student’s emotional well-being is hard when you aren’t physically seeing them, Ross said.

“I keep in contact with my students who are struggling with mental health issues such as anxiety during this time,” she said in an email.

[Related: How to Help Struggling Kids During Coronavirus]

[Related: Alabama Anti-gun Violence Activists Expect Uptick In Shootings Due to COVID-19 Stress]

“Writing and journaling have been proven to have many therapeutic benefits for mental health,” Ross said. “I feel that providing emotional support to my students is more important than teaching grammar rules and MLA [Modern Language Association] format.”

Staying out of trouble

“The same issues that plague adults plague kids,” said Mike Rollins, retired director of Coosa Valley Youth Services in Anniston, Ala.

If anyone knows how hard this time might be for teenagers, it’s Rollins, who spent 40 years operating Coosa Valley’s residential diversion programs for minors in the juvenile court system in Anniston and 10 surrounding counties.

It’s important to connect with young people by providing “something they can really get excited about,” he said. Whatever they’re into — music, painting, gardening — parents should try to plug kids into life-giving activities.

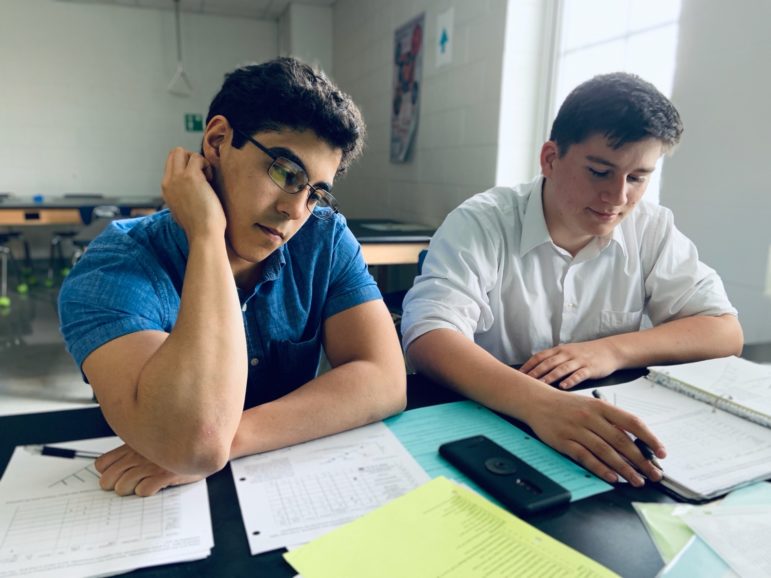

Courtesy of Omar Mohammed

Ending the school year prematurely was “bittersweet,” said senior Omar Mohammed (left), at Spain Park High School in Hoover, Ala.

Of course, the same as connecting to the internet, what resources and activities kids have access to, Rollins said, often depends on where they live.

He now travels the state, training law enforcement on the legal and safe way to work with youthful offenders.

“I don’t think I really understood the scope of poverty in the South,” Rollins said. “Some of these police departments are Taj Mahals, and some are absolute dungeons. The same goes for neighborhoods. Some of the places in Alabama are really strapped, and it’s a very depressing thing and creates a sort of helplessness and hopelessness about finding a way out.”

The kids he worked with got in trouble for different reasons — from frequent truancy to theft. They came from different backgrounds. But, Rollins said, they have one thing in common, like any kid: Youth are more vulnerable in high-stress situations, and as a result act out.

In the wake of coronavirus, Rollins is worried for kids in areas with fewer resources. He’s concerned kids’ basic needs won’t be met in households where parents have lost jobs because of coronavirus. He’s worried that stressed-out parents are more likely to harm their children when kids aren’t being seen regularly by mandatory reporters, educators and social workers who are required by law to report suspected abuse. And he’s worried about the number of firearms in homes after panic over the coronavirus caused a historic increase in gun and ammunition purchasing.

“You got a lot of new gun owners and a lot of people that don’t know what they’re doing,” Rollins said. “And a lot of them are probably so scared that they’re keeping their guns readily available, which means, of course, they’re available for kids as well.”

As coronavirus continues to disrupt daily life, anti-gun violence advocates worry the communities hit hardest will see spikes in shootings.

“You have teenagers with nowhere to go, nothing to do, nothing to occupy your time. They were already living in a stressful situation. Their stress is just being compounded. Guess what they’re doing. They’re picking fights,” said Onoyemi Williams, an anti-gun violence activist in west Birmingham, a low-income, predominantly African American community. The same population at risk for gun violence is high risk for coronavirus, which is disproportionately killing African Americans, she said.

For people living in already traumatic or stressful situations, coronavirus is compounding those feelings, Williams said. “As we continue to go through this, we expect to see the violence hit.”

Shenitha Christian, a social worker with Family Links, a nonprofit that offers education and counseling for juvenile offenders and their parents in Calhoun County, Ala., is trying to keep kids out of trouble.

“It’s a misconception that all these kids come from bad homes with drug abuse or violence,” she said. “Some kids just get in with the wrong crowd even when the parents are there and active.”

“My biggest concern is that we want them to improve when they’re with us. This is an opportunity for these kids to get back on their feet, education-wise,” said Jon Garlick, the interim executive director of Family Links. “And then my other fear is since they’re home Monday through Friday rather than with us, they have more opportunity to get in trouble.”

Every Wednesday, Christian checks in with kids who are participating in Family Links’ 20-week program as part of juvenile court. She said the students she works with are doing well, possibly because they were used to being separated from the regular school system and because of the relationships they have with her team. If one of her students gets in trouble right now, they risk entering juvenile detention.

“Kids like a schedule. The more normal routine, the better the foundation, the more opportunities for the child to thrive,” Garlick said, suggesting all families try, despite the circumstances, to keep to a routine to help everyone’s coping skills.

“Don’t stay on the internet. Don’t stay looking at social media. Don’t constantly watch the TV for news,” Garlick said.

‘Be patient with us’

For Omar Mohammed and most teenagers in Alabama, quarantine was a new experience. He was finishing his senior year at Spain Park High School in Hoover when schools shuttered.

“It’s bittersweet. We’re jump-starting our adulthood,” he said. Mohammed, 17, is an AP student and the vice president of Birmingham Youth Action Committee (BYAC), a nonprofit that organizes youth volunteer work in Birmingham metro communities.

Mohammed and his friends in the BYAC are organizing online now, encouraging young people throughout the state to respect the safer-at-home order and practice social distancing for the good of public health. There are plans for BYAC to contact students whose families were sick or lost jobs to see how they can assist with schoolwork, studying for exams or college applications.

He had a message for parents, too: “This is a big change for us. Be patient with us.”

Jacob Frazier said patience will pay off for kids, too. “It’s important to remember that even in dire circumstances, there’s hope,” he said.

“I’m lucky to be in the situation I am,” said Frazier, who is now almost fully recovered after his accident. He considers himself lucky to be alive, walking and performing with his beloved theater group (although, now, he’s recording virtual monologues instead of enjoying the camaraderie onstage). He’s lucky to have a supportive mother. He learned a lot during his recovery, including “how to deal with the things you can’t control.”

In the coming weeks, Frazier said he’ll be watching to see what restrictions are lifted, but he’s committed to staying home until the threat of coronavirus has drastically lessened. Once it does, he said he wants a chance to say goodbye to his friends.

“We didn’t know that last day of school was the last day,” Frazier said. “I think it’d be good for all of us to get some closure so we can move on, together, for whatever comes next.”

This story was produced in conjunction with The Anniston Star. It is part of Youth Today’s project on targeting gun violence. Support is provided by The Kendeda Fund. Youth Today is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.