VIDEOGRAPHER: KATHERINE WEBB-HEHN

Tucked in the Cheaha foothills of eastern Alabama, Ranburne is home to 409 people.

Like many rural communities, the town dealt with a shortage of nearby hospital beds before the global pandemic.

Care is lacking for rural populations — already older, poorer, more likely to die from preventable illnesses and less likely to have access to mental health care.

“It ain’t all bad,” said Police Chief Steve Tucker on a rainy Tuesday morning. In a tight-knit town, he said, people look after one another. “Everybody, some way or another, is kin to one another.”

Tucker, 61, with silver hair and thin-rimmed eyeglasses, was tired from being on duty overnight. Things had been slow. He hadn’t received a single call. In a brown button-down tucked into blue jeans, he joked his job was a lot like Andy Griffith’s in Mayberry.

It was an unavoidable comparison. Three different residents asked if I needed help when I pulled into a gravel lot to take pictures of downtown, a short strip on Alabama Highway 46 serving as Main Street. Most of Ranburne’s public spaces are in a row: the school, the churches, a gas station called Jumpin’ Jax, Town Hall and the small cinder block police station. Tucker, who tries to visit each of these places daily, works at a desk beneath a photo of himself at 27 when he joined the police force.

“I’ve never even fired my weapon at anybody,” he said.

Underfunding, shortages

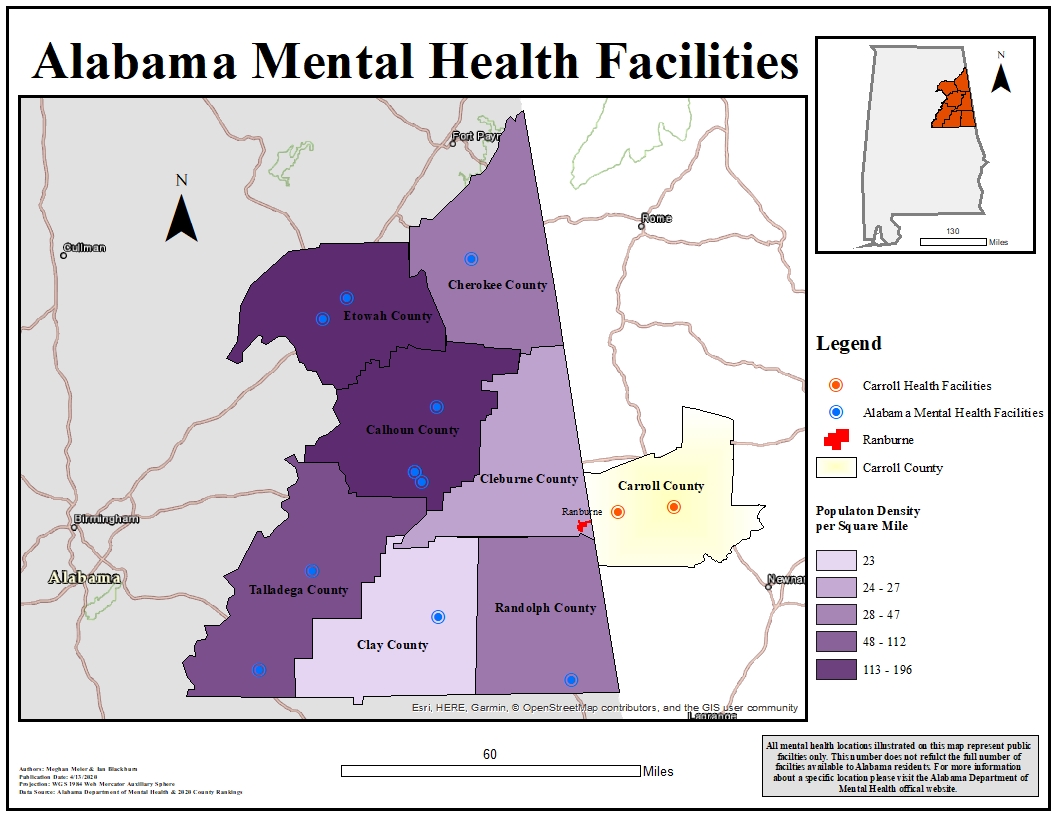

Keeping peace is easy when you know all your neighbors. But rural communities face unique challenges, especially when it comes to mental health care. In Alabama, seven rural hospitals have closed in recent years and many of the remaining facilities are at risk of closing, according to a report this year from the Chartis Center for Rural Health.

Ranburne is a 45-minute drive to the nearest in-state hospital in Anniston or 20 minutes to Highland Health System, a regional provider with a location in neighboring Heflin, Ala.

Even when rural residents are able to access mental health care in nearby towns, Alabama lacks broad services. Public health experts warn the state’s mental health care infrastructure is underfunded from the ground up — from the lack of community-based counseling to a shortage of crisis beds in hospitals. The result is rural people often have mental illness that is not treated, according to the National Institutes of Health. Untreated mental illness contributes to problems with relationships and work as depressed, anxious, psychotic or suicidal thoughts overwhelm.

When families are in a mental health crisis without anywhere else to turn, they often call police for help. But law enforcement officers are limited in their ability to assist if a person declines voluntary hospital evaluation. Without a system of support, an already vulnerable population faces criminalization of their disease.

“If they ain’t broken the law, there ain’t much I can do about it. We try to get the family to get the person into care,” Tucker said. But many people refuse.

He prefers to leave the ill person at home rather than lock them up, which is common elsewhere when law enforcement determine the person to be safer in custody. Instead, he asks if firearms are present and if the family wants him to keep any weapons at the station until things are calmer. He has no grounds to remove the firearms without a court order. All he can do, he said, is return to check on the family.

It’s not a perfect solution, he said.

“I have seen a lot since I been policing here, a lot of suicides,” Tucker said.

What happens without care

On July 22, 2019, the Ranburne Police Department received a call that John David Brown Jr. had locked himself inside his home. His wife was worried he’d killed himself.

“Me and John D. had been friends since way before I started policing,” Tucker said. When Tucker got to the house, something was blocking the front door. Afraid it was Brown’s body, he pushed gently before realizing it was a chair.

That’s when Brown fired a shot. Law enforcement from neighboring counties arrived for backup. Tucker spent nine hours trying to talk his friend down, but Brown, who fired 20 more rounds, wouldn’t talk.

“I gave the order for them to go ahead and do what they needed to do,” Tucker said. It was the first time in his career he failed to calm someone on a crisis check. “I didn’t shoot him, and I don’t know who did. Don’t want to know.”

Brown’s autopsy revealed methamphetamines. The chief said he didn’t know how badly his friend had been struggling.

“He was disabled, stuck at home. And his wife worked hard … long hours at Wal-Mart. I think it got to him,” Tucker said.

Drug addiction and mental health issues are closely related, and without access to mental health care, people often self-medicate, according to the National Institutes of Health.

“I hate seeing anybody like that. Don’t know where you been, how you got there. It’s got to be bad,” Tucker said.

For weeks after Brown’s death, Tucker considered retiring early. Now, he’s hoping his community can find better ways to address drug rehabilitation and mental health care.

“It’s just something this country’s going to have to solve in some way or another,” he said.

When firearms are present, a crisis check can turn lethal quickly. Restrictions that attempt to prevent firearm access for people who are a threat to themselves or others often aren’t successful in Alabama.

So-called “red flag” laws give courts power to temporarily ban gun ownership for anyone deemed dangerous. Seventeen states have these laws, but not Alabama. Here, a red flag law for domestic abusers mimics federal law, forbidding known abusers from owning a firearm if there’s a recorded protection-from-abuse order.

But dangerous individuals in the U.S. often keep their guns because of sales loopholes and systemwide failure to follow through on the law. A bill that would allow people suffering suicidal ideation to add their names voluntarily to a “do not sell” firearm list has gotten no traction locally. And though probate judges are required by law to report the names of people committed to psychiatric treatment to the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency, reporting in the state is weak.

Ranburne is in Cleburne County, where the probate judge said he would initially not follow this order but now complies with state law.

The real threat

Studies show people with mental illness do not pose a higher risk of violence to others than the greater population. The greater risk is to themselves.

In Alabama, the most recent data from the state Public Health Department reports 788 people died by suicide in 2016, compared to 543 homicides. Firearms were used in 70% of the state’s suicide deaths.

[Related: Q&A: How We’ve Criminalized Mental Illness]

[Related: People Stocking Up On Guns Though Safety Classes Unavailable]

[Related: Therapists Urge Seeking Help Immediately After Suicidal Thoughts]

“There’s no single solution here,” retired Chief Deputy Jon Garlick said. The first mental health officer for neighboring Calhoun County, Garlick helped establish its mental health court.

Because there’s no way to prevent someone who has been committed for mental illness from buying a gun through a gun show or from an individual, he said it’s important to focus on getting people the care they need.

An estimated 20 to 25% of Americans have a mental illness, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Half of Americans will have a psychiatric disorder at some point in their lifetimes. Those numbers include depression, addiction, impulse and anxiety disorders. Six percent of the population suffer more debilitating mental illnesses, which includes schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and post-trauma stress disorder.

“Only 1% are so mentally ill they cannot function outside of structured care,” Garlick said.

The majority of people with mental illness respond well to treatment. With a combination of medicine, therapy and lifestyle habits, he said, people often successfully manage their illness.

There are systemic solutions to ensure people are screened and receive the right treatment, but, he said, “Nobody wants to undertake [broad reform] because it’s very expensive.”

Far from help

The closest hospital to Ranburne is actually only 17 miles away — in Carrollton, Ga.

If Chief Tucker could put someone in Ranburne on an ambulance to cross state lines, they’d receive broad mental health services.

“In Georgia, the state helps fund hospitals to provide more crisis beds,” Garlick said. If someone is clearly in need of help, then a police officer can take the person to any emergency room where that person will receive evaluation.

“We have roughly 400 treatment beds” in Alabama, Garlick said. Based on standard recommendations for crisis beds, the state needs 2,400 beds.

Meghan Meier and Ian Blackburn/Kennesaw State University Department of Geography and Anthropology

.

Being short 2,000 beds means psychiatrists cannot keep patients in treatment for recommended time periods because other people are waiting for care. Too often, they’re waiting in jails.

Regional Medical Center in Anniston has 20 beds designated for psychiatric care but needs at least 50 for Calhoun County, Garlick said. People in neighboring rural counties, including Ranburne in Cleburne County, also rely on the hospital for care. Those 20 beds are occupied by people referred through private medical practices or those who voluntarily entered the emergency room for an evaluation. RMC is not a designated mental health facility. So the hospital is not required to take emergency holds or judge-ordered commitments.

Because of this, law enforcement officials have to make critical decisions during crisis checks. And most officers aren’t counselors like Garlick. They haven’t received extensive mental health training.

“The sad part is, we’ve become very good at criminalizing mental illness,” Garlick said.

Many officers arrest someone during a mental health crisis, charging them with misdemeanor misconduct in order to take them into custody to await screening, he said. Otherwise, officers might have to leave someone at home who is clearly a danger to himself or others.

When people with mental illness do commit crimes, jail stays are often longer than for their counterparts. Being in jail instead of psychiatric care, people stand to lose their health insurance through Medicaid, their jobs, their homes and social status.

In Calhoun County’s mental health court, inmates must plead guilty to a charge in order to swap time incarcerated for outpatient treatment. Studies show mental health courts reduce recidivism, but it’s unclear how much an individual’s overall mental health improves without ongoing care.

It’s important to make sure people don’t wind up back in jail, but that’s not the only measure of wellness, better quality of life or safety, Garlick said.

Suggesting solutions

A package of mental health bills to address crisis care is moving through the state Legislature with bipartisan support. But advocates for people living with mental illness said more needs to be done.

“Our hope would be that through better or more adequate funding of mental health care in the community, individuals could obtain adequate mental health care before they are in crisis,” said James Tucker, director of the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program. Funding to community mental health centers was cut by $40 million during the last recession and never fully restored, he said.

“Adding beds or new crisis facilities can only be part of the solution,” said Fredrick Vars, author of the voluntary “do-not sell” firearms bill. His advocacy is influenced by his personal experience. When Vars was in his early 30s, he suffered a mental breakdown and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. During that time, he struggled with thoughts of suicide. He’s grateful he received care, didn’t have access to a gun and had a supportive family.

Mental health care experts said supportive families can make a difference in someone getting care.

“We have a lot of stigma that prevents people from getting care,” said Judith Harrington, a counselor and associate professor at the University of Montevallo. “People, and especially men, are socialized to not be help-seeking. ‘You’ll be considered crazy or weak.’ That’s what they hear. So, what we can do in prevention every day is to make ‘help seeking’ socially acceptable.”

When people consider mental illness a character flaw rather than a symptom of illness, they are less likely to receive help, she said. So, it’s important to make sure people are aware that mental illness is “neurological, biochemical.” And it’s important, Harrington said, to talk openly about mental illness and suicide — to not hide either in the media or in personal relationships.

We need community visibility for mental health screening and resources, similar to preventative efforts for cancer or diabetes; otherwise, people will misunderstand or deny mental health problems, Garlick said.

And in rural communities, where some churches won’t even allow people who die by suicide to be buried in cemeteries, Harrington said stigma runs deep. The result is that people suffer with mental illness silently — until crisis care is needed or, in the worst cases, tragedy happens.

In Ranburne, Tucker is still reckoning with the loss of his friend.

“I just put in the back of my mind,” he said, “and go on.”

If you or someone you know are in need of mental health assistance, contact the National Alliance for Mental Illness at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264) or info@nami.org.

This story was produced in conjunction with The Anniston Star. It is part of Youth Today’s project on targeting gun violence. Support is provided by The Kendeda Fund. Youth Today is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.

This story has been updated.