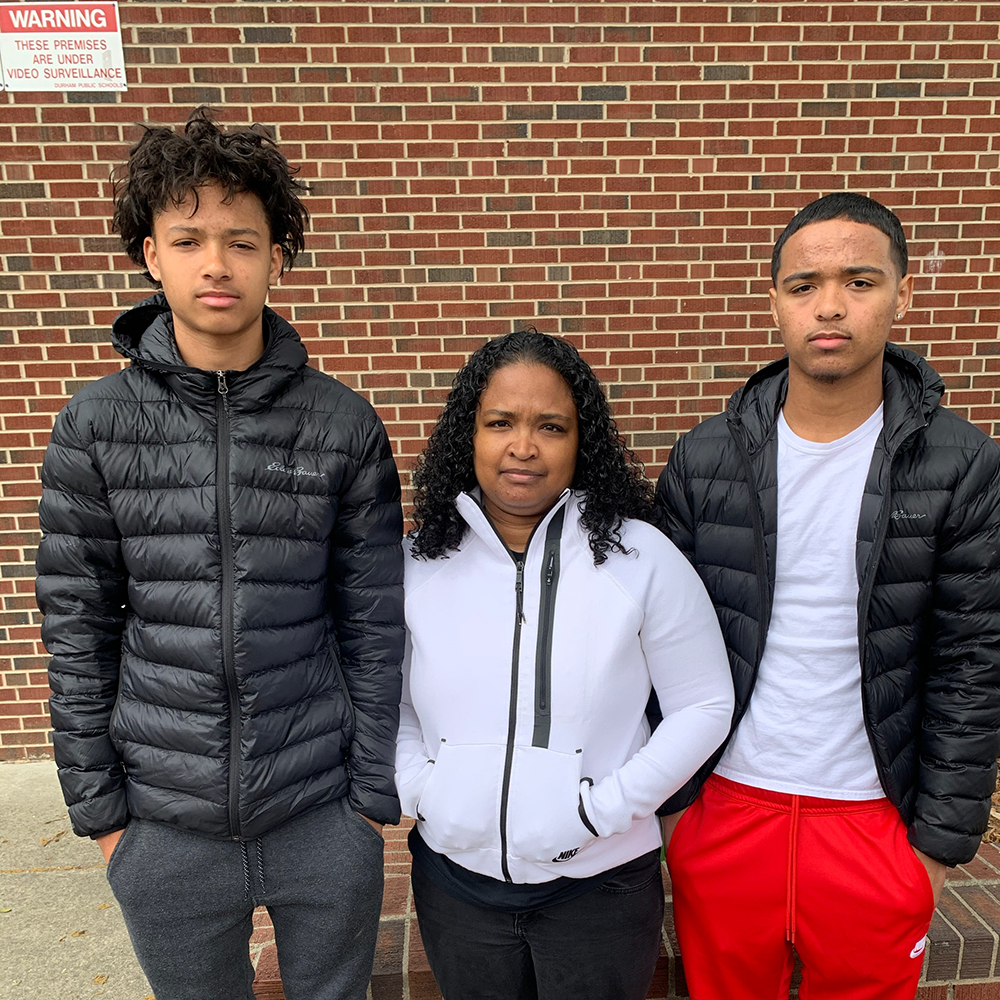

Family photo

Xavier Sorensen, 16 (left), and Micah Sorenson, 17 (right), were both “casualties of a racist system” at the Durham School of the Arts system in Durham, N.C., says their mother Fatimah Salleh (center). Both are thriving at Southern High School.

Unpacking a book bag “noisily” — unacceptable.

Chewing a Jolly Rancher during school — in-school suspension.

Having a laugh more audible than his friends — disruptive: in-school suspension.

Lightheartedly horsing around on the playground — in-school suspension.

“We don’t know how many students are casualties of a racist system, in which they are punished for being in their bodies, for being brown and black kids, and we’ve got to do something,” said Fatimah Salleh, mother of two former students at Durham School of the Arts (DSA) in Durham, N.C. “If we are not really aggressive about it, then it will be the way America has always deemed it to be.”

Ricky Watson

Principal David Hawks of DSA could not be reached for comment after repeated attempts.

At DSA, 16.56% of black males were sent to a Restorative Practices Center, 11.17% of Hispanic males and only 5.16% of white males, according to the 2019-20 Quarter 1 Report from Durham Public Schools. DPS replaced in-school suspension with the centers in the 2018-19 school year. Students are sent to Restorative Practice Centers to reflect upon their actions and work toward reconciliation with the party the disciplinary infraction was committed against. While in-school suspensions focused primarily on punishment, the centers focus on temporary removal and reflection.

“The primary reason we made this change was to initiate our transition to being more restorative in our approaches to school discipline,” Daniel Bullock, executive director for equity affairs for DPS, said in an email.

Will raise the age lower court referrals?

Out-of-school suspensions and court referrals are a major area of concern within DPS and North Carolina in general, said Ricky Watson, executive director of the National Juvenile Justice Network. North Carolina became the last state to raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction for nonviolent crimes to 18, effective Dec. 1, 2019.

Eric Zogry

It’s too early to determine the effect this legislation will have on the juvenile system, said Eric Zogry, a juvenile defender with the North Carolina Office of the Juvenile Defender, adding that right now the transfer of caseloads is a trickle rather than a flood.

The raise the age movement has made addressing the school-to-prison pipeline of the highest importance, Watson said. To keep the juvenile system from becoming overly stressed in terms of caseloads, he suggests restorative justice and other such alternatives to court referrals for punishing students for nonviolent crimes and misdemeanors.

“When we have kids with the more serious felonies, that suggests needs around retraining behaviors, that’s where more of our resources need to be spent,” Watson said. “Not on those minor issues that kids might grow out of themselves.”

To do this, the state and school districts must work together to provide adequate resources for teachers and administrations to foster happy and healthy environments for all their students, he said. Given proper resources, schools should use alternatives to suspensions that focus on dispute resolutions rather than just punishments, ultimately setting children up to be productive members of society, he said.

“We want to make sure administrators feel empowered to do that instead of sending the students out of school, where, let’s be honest, they all need to be,” Watson said.

Zogry said the majority of offenses that bring youth to juvenile court are school-based: disorderly conduct, fights, assault, etc. School-based offenses are the only type of offense that has not decreased over recent years.

“There is still an overwhelming disproportionate amount of black students being prosecuted, and there hasn’t been enough attention paid to this problem,” he said. “The issue of implicit bias is a big problem in the juvenile court.”

What is being seen in the state’s juvenile court could be a direct reflection of the implicit bias and inequitable design of local schools’ punishment systems traveling through the school-to-prison pipeline.

The state Crime Commission’s Disproportionate Minority Contact Report of 2019 used a Relative Rate Index to measure the level of disproportionality in the juvenile court system at different stages in the context of race. A perfectly proportionate system, meaning minority youth and white youth are processed at the same rate, would equal one; anything above this reveals disparity. Durham County’s index for black youth was 1.8.

“We need to fix it; a lot of people just avoid the issue and we can’t do that anymore,” Zogry said.

The suspension experience

When Salleh’s then-16-year-old son Micah came home from a day of in-school suspension at DSA in 2018 and described the conditions, she didn’t believe him and chalked it up to his dramatizing the situation. He had received a day of in-school suspension for horseplay and another two days for laughing during his original punishment.

After he insisted he was telling the truth, Salleh decided to attend his last two days of suspension with him.

“I went to prove to him that it can’t be that bad and that maybe he was exaggerating,” Salleh said.

Walking into the room the next day, she swallowed the terrifying realization that she was wrong.

Four dismal walls enclosed a small, silent space. In two rows of desks, one butted up against the wall and the other directly behind, sat mostly boys of color (eight of the 11 students present). The school includes 35.1% white students, 34.8% black students, 21.9% Hispanic students and 60.5% girls.

The students had to keep their heads off their desks, for fear of the unwritten rule that if they fell asleep, they were stuck in that room for another seven-hour shift.

So, for seven hours, they sat looking at the wall, ate lunch looking at the wall, and were given three bathroom breaks of five minutes each. Students did not have access to phones and most did not even have their books and assignments, something that shocked Salleh.

All students are enrolled in seven classes and many were not receiving any work from their teachers. DSA’s system was debilitating, she thought. These students spent a whole day at school, in silence, learning nothing, and many falling behind in their classes and falling into utter discouragement, she said.

Leaving the building teary-eyed, Salleh knew she must take a stand. She felt she had to fight for those children, staring at that wall.

“White students are allowed to be kids,” she said. “I think that what is disruptive, discourteous behavior has far more leeway in a white body than it does in a black or brown body.”

DPS strategic plan

The Durham Public Schools’ report also showed that 1,056 black and brown students were sent to a Restorative Practices Center as opposed to 66 white students, showing that this is a county-wide issue in Durham County and is not DSA-specific.

The 2019 Racial Equity Report Card for Durham County Schools, produced by the Youth Social Justice Project about public schools, revealed that in the 2016-17 school year “black students were 9.7 times more likely than white students to receive a short-term suspension.” It also showed that “black youth were 10.2 times more likely than white youth to be referred to a juvenile delinquency court.” In 2017, black youth accounted for 91.2% of juvenile detention admissions.

DPS’ recent battles with providing an equitable education and fair punishment system for all students regardless of race, ethnicity, economic background and condition are part of a larger war. There are many more students like Salleh’s son, some known and others suffering silently.

On April 16, 2013, the Advocates for Children’s Services of Legal Aid of North Carolina filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights on the grounds that DPS’ out-of-school suspension system violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The complaint claimed that the system inequitably punished black students with disabilities, black students and students with disabilities.

For more information on Racial-Ethnic Fairness, go to JJIE Resource Hub | Racial-Ethnic Fairness

“I think any parent of color in any school district feels and is aware of the discrimination that goes on … it wasn’t individual intentional discrimination, it was the disparate impact,” said Jennifer Story, supervising attorney at Advocates for Children’s Services at Legal Aid NC. “It was that their policies or practices are having disproportionately negative impacts on students of color with disabilities.”

The Office for Civil Rights wrote in the resolution agreement in 2018 that “African American students were disciplined at a rate disproportionate to their percentage of the population among most offenses” and students with disabilities were also overrepresented in discipline statistics. Its analysis also found that the schools giving out the most suspensions were those that had an average number of students who got free and reduced-price lunch.

Story remarked on how compliant and willing to cooperate DPS was. They admitted to the disparities caused by their policies and were willing to work to fix it, begging the question of why they did not address it earlier.

“It’s just easier to stick with the status quo, and why we feel that especially complaints of this nature are so crucial is that they require system-level change,” she said.

Under the agreement the district had to designate a discipline supervisor who had experience dealing with nondiscriminatory policies, revise the definitions and categories of misconduct, collect data on disciplinary practices and train staff and anyone else who could potentially give out disciplinary referrals.

As a result of the investigation, DPS launched a strategic plan consisting of five priorities: “increase academic achievement,” “provide a safe school environment that supports the whole child,” “attract and retain outstanding educators and staff,” “strengthen school, family, and community engagement” and “ensure fiscal and operational responsibility.”

Priority number two aims to have all schools in the district adopt and implement a new cultural framework backed by research by 2023. They hope to figure out which policies are causing the disproportionate rates of suspension between black and brown students and white students. When suspensions do occur, the plan proposes that the experience be more restorative, monitored and that each student suspended (whether in school or out of school) still receives educational programs.

Dan McKinney, the youth engagement strategist at Made In Durham, said that while this priority may lower out-of-school suspensions, it does not specifically target Restorative Practices Centers. Therefore, not much will change with schools that are already keeping out-of-school suspension rates low.

“Very little has changed; while the district has tried to make strides in this, it is a huge problem and we have allowed administrators to stay in place, who have really allowed racism to flourish,” Salleh said.

Zero tolerance a problem

McKinney said the disparities in the punishment system could be explained by implicit racial bias and also structures built into the education system that often cause white students to thrive and harm students of color.

He gave the example of the zero tolerance policy of tardiness. It is more likely that white students have easier access to a means of getting to school on time, whether it be a bus or otherwise. Students of color may have a harder time accessing bus routes, therefore the policy on tardiness already disfavors them — even if it was not set up to do so.

“We have got to get rid of the zero tolerance policy,” McKinney said. “Historically, zero tolerance policies impact people of color more heavily.”

He believes that not only should parents and others listen to those who are being affected, but they should give them part of the decision-making power. They need a voice.

That’s what Salleh is working toward with DSA.

She believes that DPS is turning a blind eye to DSA’s inequities because they consistently have College and Career Readiness Percentages higher than the district average and state average for all subjects.

“I don’t have a kid there anymore, but people are still reaching out because it’s still a big problem,” Salleh said. Other parents and even teachers are scared to speak up in fear that their kids will be singled out or that their jobs would be on the line, she said.

A DSA student from an Arab country told her, “You know, they used to beat us if we got out of line, they used to physically hit us and DSA is no different. It just prepared me because they will beat you down in every other way, emotionally.”

A friend of her son’s dropped out after receiving repeated in-school suspensions for falling asleep during the previous sessions. He became so hopeless about catching up in classes that he thought there was no alternative. Her son never heard from his friend again.

As for Salleh’s two sons, Micah, now 17, and Xavier, who is 16, both “casualties” of the DSA system, they are doing well at Southern High School. One has been invited to become a member of the National Honors Society, something he was never even considered for at DSA, and both were praised by teachers in parent-teacher meetings.

“This is where the tragedy happens, is that I began to believe DSA about my kids, I began to believe them,” Salleh said, with obvious pain in her voice.

Imagine living by a stream, McKinney said. Each day a baby floats down the stream and each day you take it out of the river, feed, clothe and take care of it. Day after day, baby after baby. Feed, clothe, care.

“One day, wouldn’t you think to walk upstream and see who’s dropping the babies in the river?” he asked.