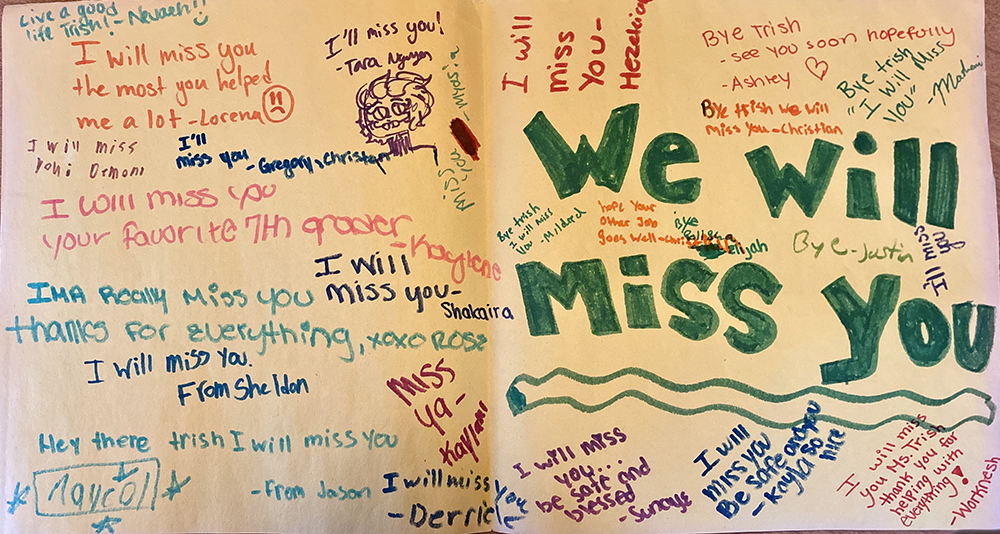

Card provided by Patricia McGuiness-Carmichael

Many out-of-school time programs experience frequent staff turnover, to the chagrin of leaders in the field. Some estimates put the turnover rate at 40%.

Children feel the impact.

In one middle school youth development program in Boston, fully one-third of kids interviewed said they considered quitting the program when a staff member left.

“They get used to one [staff] person. They get close,” said Patricia McGuiness-Carmichael, who researched the effect of turnover during a fellowship sponsored by the National Institute on Out-of-School Time.

She interviewed kids and surveyed staff at a program serving 250 students in five Boston public schools. Having supervised AmeriCorps volunteers working with children in the program, she wasn’t surprised at the strong feelings expressed.

“What was a little surprising was how [the students] were able to articulate their feelings,” she said. They reported feelings of sadness, frustration, anger, devastation and lack of trust, she said. Some also said they were happy for the staff member’s new opportunity.

McGuiness-Carmichael held a focus group with 13 kids — a very small sample. But she also surveyed more than two dozen current and former staff members. More than one-third of them noted difficulty handling student behavior and keeping “student buy-in with the program” as a result of staff departures. They reported trouble in building relationships.

Sixty percent of the staff were AmericCorps members who served only one year. Children often told incoming AmeriCorps members that a former member was their favorite person, McGuiness-Carmichael said. They were used to the former person’s way of doing things and resisted new methods.

Too little attention has been paid to the impact on kids when a staff member leaves, McGuiness-Carmichael said.

“We don’t ever really talk to the kids about what it means to them,” she said. And yet youth-adult relationships are central to the work of after-school programs, she wrote in the journal Afterschool Matters, where she published her research.

McGuiness-Carmichael, who has a master’s degree in social work, is now a program director with Strong Women, Strong Girls, a Boston-based multigenerational, group mentoring program serving about 1,250 elementary school girls a year.

She previously worked as family engagement coordinator and AmeriCorps supervisor at Tenacity Middle School Academy.

The middle school students she interviewed had suggestions for making staff departures less wrenching. They said they’d like to meet adults who were interviewing for the job. They suggested going on a field trip with both the incoming and outgoing adult.

Giving young people a role in staff selection could help, McGuiness-Carmichael said.

More research is needed across different youth-serving organizations to inform program practice, she said.

Not only should the field address the causes of high staff turnover, but it needs to create ways to help youth handle staff transitions — whether it’s a role in staff selection, special rituals to observe departures and arrivals, or even reconsideration of the length of AmeriCorps jobs, she said.