Photos by Baton Foundation

The Baton Foundation took its class on a field trip to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala. Founder Anthony Knight is in the center.

A small nonprofit in Atlanta fills what its founder considers a critical gap for black adolescent boys — a chance to explore their history and culture.

Not only does the organization engage boys, but it also draws their parents and other adults to events exploring black history and culture.

Twice a month on a Saturday morning a small group of boys ages 10 to 17 meets with Anthony Knight, founder, president and CEO of the Baton Foundation. On a given Saturday they might discuss how to manage money, handle an encounter with the police or what a slice of history might have felt like to people who lived through it.

“We spend four seminars going over different ways to understand who we are as human beings,” Knight said. The first four classes cover emotional and self-awareness.

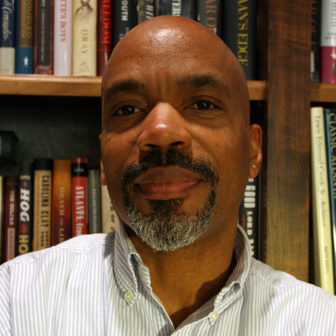

Anthony Knight, founder, president and CEO of the Baton Foundation

Other classes explore cultural heritage and black history. Boys might discuss the writings of poet Gwendolyn Brooks or memoirist Olaudah Equiano, whose account, which includes his enslavement as a child, was instrumental in the British abolition of slavery in 1807. Another series of classes addresses self-mastery and how to deal with challenging life situations, including the example of being pulled over by the police.

In addition, the Baton Foundation holds community events for the public two to three times a month, often at Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue Research Library. In November, the organization screened the film “The Last Black Man in San Francisco.” In December, author Jelani Favors discussed his book about historically black colleges and the role they’ve played.

Working with young people is not complete unless the adults in their lives are also engaged, Knight believes. Otherwise, kids go home and are not supported in their new knowledge, he said.

He recently organized a discussion of the opera “Porgy and Bess” along with the performance of two selections from the show. The original play was written by a white couple in Charleston, S.C., he noted. That fact always sparks discussion about creating art outside of one’s own experience, Knight said.

Why cultural identity is important

Taken together, the Baton Foundation’s offerings are a deep dive into the cultural currents of being black in America.

Its work with youth is based on the idea that a strong cultural identity strengthens young people. Youth development research also supports this idea.

“Culture is the fundamental building block of identity, and the development of a strong cultural identity is essential to children’s healthy sense of who they are and where they belong,” according to the Early Learning Years Framework for Australia.

Youth with a strong ethnic identity have more coping strategies, according to psychologists Susan D. McMahon and Roderick J. Watts. Young people who are racially in a minority have a more complex task of sorting out their cultural identity, but a coherent sense of identity is linked to feeling more positive about oneself and less likelihood of risky behavior, other research has noted.

Knight, whose parents were from Florida, grew up in New York City.

He earned a master’s degree from George Washington University and has spent 20 years in museum consulting, education and management.

At one point early on in his education, he realized: “I really did not know much about black history and culture.” That lack of knowledge is common, he said.

He decided he could use his museum work to educate people.

The Trayvon Martin connection

Then high school student Trayvon Martin was shot and killed. It happened in 2012 in Sanford, Fla., the town Knight’s parents and grandparents were from. The shooter, George Zimmerman, was found not guilty.

“I kept hearing black people casually and in conversation being shocked by the acquittal,” Knight said.

“It was a wake-up call to me: People can still kill unarmed people in this country,” he said. “I had to do something.”

Not long afterwards he had a conversation with former civil rights activist Lonnie King, who led protests against segregation in Atlanta in the 1960s.

King told him the effort to educate a new generation is like a relay race: “‘We’ve got to [say] to our children that the fight for human rights and civil rights is not over,’” Knight recalled.

The conversation had a profound effect on Knight. It became important to him to take part in that relay race and pass the baton to the next generation — hence the name Baton Foundation.

Knight founded his nonprofit in 2015, supported by small, individual contributions, he said. For four years, he’s held the Saturday classes, which run all year. He can serve only 15 boys.

Knight works a full-time job with the city of Atlanta, running a program that arranges for Atlanta Public Schools students to attend cultural events at city venues, from the ballet to The King Center to the Georgia Aquarium.

The small number of students the Baton Foundation works with doesn’t faze him. He values small group interaction, he said.

The foundation’s goal is to strengthen black boys emotionally, culturally and intellectually. It affirms black people in a society that marginalizes them, according to the foundation.

Knight said he’s heard many a conversation indicating ways that black people don’t value themselves in a society that doesn’t value them. The Baton Foundation, however, challenges the negative things children learn about race in the larger society, Knight said.

It’s important to “teach our children the truth — the good, the bad, and the ugly,“ he said.