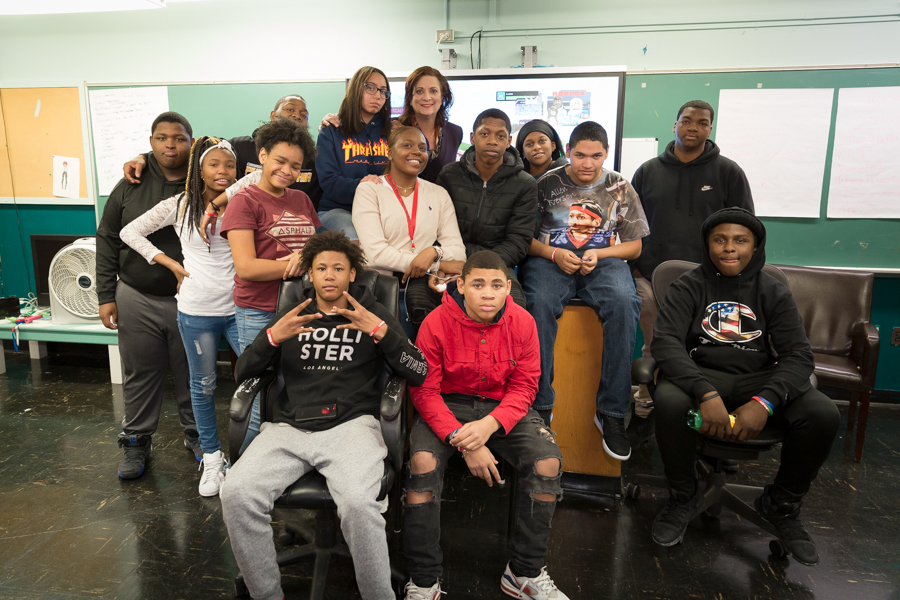

Photos by Sunrise of Philadelphia

Sunrise works with students at schools in Philadelphia.

On an afternoon in October, kids in the Sunrise of Philadelphia after-school program made tissue-paper marigolds, assembled little altars and created masks. It was the Day of the Dead celebration held by Sunrise partner, Fleisher Art Memorial.

They wrote poems about people who were no longer with them, either lost to death or simply separated across distance — a possibility in this largely immigrant and refugee community.

The activity gave them a chance to explore loss and sadness, which — perhaps unintentionally — fit right into Sunrise’s focus of being a trauma-informed organization.

“One of the things you can do with your staff and students [in a trauma-informed organization] is help them make sense of their experiences,” said Marina Fradera, trauma and curriculum specialist at Sunrise. She is leading the effort to integrate an understanding of trauma into Sunrise’s programs and practices.

[Related: Avoid Simplistic Thinking About Trauma-informed Care, Some Say]

[Related: LA’s Best Sees Increase in Mental Health Issues, Responds with a Focus on Trauma]

Out-of-school time organizations across the country are increasingly exploring ways to serve students impacted by trauma, but few are taking a comprehensive approach, according to a report recently released by the expanded learning unit in the Los Angeles County Office of Education and by LA’s Best.

Most begin by using their resources to train staff, wrote report author Jimena Quiroga Hopkins.

But how do they incorporate the new knowledge into their programs?

Fradera said the four principles delineated by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) are a guide for organizations:

- Realize the widespread impact of trauma and the potential paths for recovery

- Recognize the signs and symptoms

- Respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures and practices

- Resist retraumatization.

“Trauma-informed care is often referred to as a paradigm shift as well as a set of strategies,” she said.

But practices can be implemented in a structured way, she said.

The hard places

Sunrise is a 20-year-old nonprofit that serves about 1,000 students in after-school programs at five K-8 schools and one high school, most of which are in South Philadelphia. It’s a low-income area where most of the kids are impacted by poverty.

A 2012 survey of adults’ adverse childhood experiences in urban areas of Philadelphia found that 40% had witnessed violence while growing up (seeing a stabbing, shooting or beating) and 34% reported racial or ethnic discrimination. Twenty-four percent had lived in a household with a member who was mentally ill, and nearly 13% had a household member who was sentenced or served time in prison.

Adverse childhood experiences are not the same thing as trauma, but trauma occurs when the events overwhelm one’s ability to cope.

“Kids have it tough in our community,” said Vincent Litrenta, founder and executive director of Sunrise. It’s always been important to be trauma-sensitive, he said.

Through a 21st Century Community Learning Centers grant and assistance from the local United Way, Sunrise began training staff in 2018 at Lakeside, a Philadelphia trauma training institute and operator of therapeutic schools.

Currently 60 staff members have been trained, and 15, including two directors and all site supervisors, have taken a longer course, Fradera said. Sunrise also brought partners to the training, including people from the Promise neighborhood where one after-school site is located, and the refugee services agency SEAMAAC.

Giving staff the tools and resources to address their own stress is an important element.

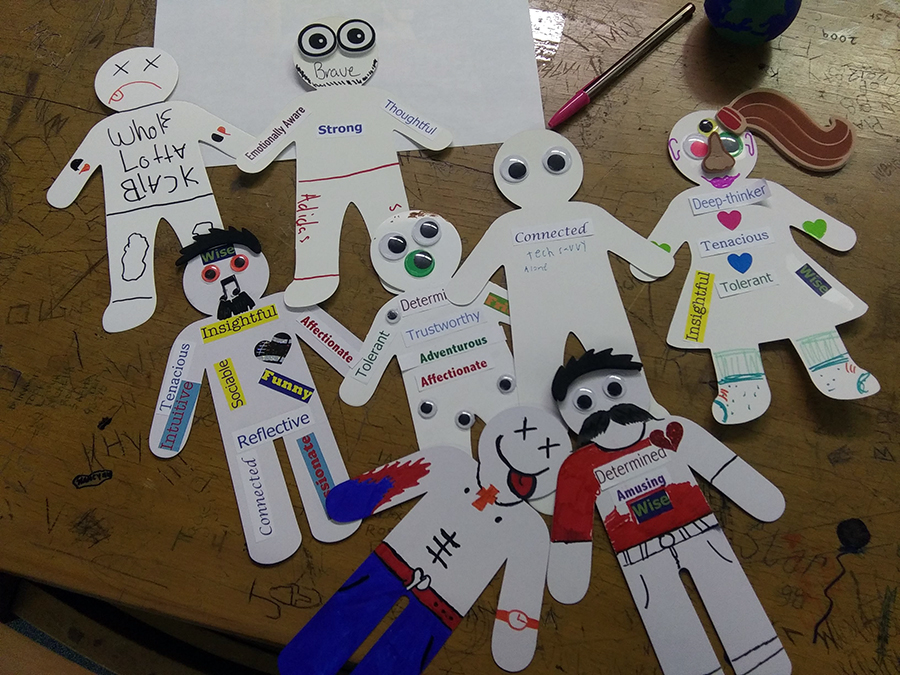

Students were encouraged to find positive words about themselves at the most recent teen trauma workshop.

Staff members devise a “safety plan,” Fradera said. She is referring to actions as simple as drinking a glass of water or taking deep breaths.

“If you plan it out now, you don’t have to think about it in the moment,” she said.

Trauma-informed practice is also about managing staff expectations of what a kid is capable of when they’re upset, Fradera said.

Staff learn to see that behavior, learning and relationship problems that kids have may be natural reactions to trauma and deserve to be handled with care and understanding, according to the recent Child Trends report “How to Implement Trauma-Informed Care to Build Resilience to Childhood Trauma.”

When kids are upset and acting out, it does no good to give an ultimatum or talk about consequences, Fradera said. At a certain level of upset, kids literally can’t process it. Part of the training about trauma is learning how the brain behaves.

When kids are upset, “give them language,” she said. Narrate the behavior, she said, by saying things like “This is upsetting.”

Give them space to calm down, she said. Once escalation has passed, kids may appear visibly tired, she said.

“That’s a point at which conversation can happen,” and that’s when consequences can be discussed, she said.

Staff at Sunrise tell her they’re giving kids “wait time.” “They say they no longer yell.”

Developing resilience in kids

Children and youth who have experienced trauma can later be impacted in both positive and negative ways that influence their ability to cope and heal.

The language around trauma can sometimes lead to people feeling hopeless, Fradera said. “But people impacted by trauma can heal,” she said.

Resilience is the ability to bounce back, and protective factors are the padding that allow for resilience, she said. Youth development programs are already positioned to provide many protective factors.

Some of those factors as enumerated by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network are:

- Support from friends and surrounding adults

- Being in an environment that feels safe

- Positive sense of self-worth

- Sense of self-efficacy

- Developing talents or skills

- Developing coping skills.

Specific activities at Sunrise include use of the book “Once I Was Very Very Scared” with younger children. It’s a jumping-off point for talking about fears and healthy ways to self-soothe, Fradera said.

The organization also will be using the resource Sesame Street in Communities, which explores topics including parental incarceration, divorce and addiction.

Sunrise is planning to use a curriculum from Storiez, which helps teenagers create a narrative around a difficult experience.

Last summer, teens in a Philadelphia youth employment program worked in jobs Monday through Thursday and came to Sunrise on Friday for what was termed professional development. In addition to learning job skills such as phone etiquette, they talked about what to do when feeling stressed at a workplace.

To Litrenta, a trauma-informed practice is about addressing the whole child. Partnerships with other organizations are very important, he said. A partnership with schools allows the school and after-school program to work together to meet the needs of kids, and partnerships with community organizations help Sunrise connect kids with mental health and other services, he said.

This story has been updated.