Michael Tashji

Matthew “Fire” Mishefski now lives in Union Square Park, after spending years in the foster care system.

Matthew “Fire” Mishefski’s experience with homelessness is the last of three stories on LGBTQ homeless youth as reported by the JJIE’s New York City Bureau. He uses the pronouns he/him.

NEW YORK — Matthew “Fire” Mishefski was days away from completing his makeshift encampment. After years of homelessness, the 24-year-old knew what he needed to successfully make it on the streets. It consisted of a bike, trailer, hammock, cooler, electric stove, solar panel — he was fully equipped to survive frigid Northeastern temperatures.

“I stopped begging because I didn’t need to anymore,” Mishefski said. “I was working. I was a carpenter. Jesus was a carpenter. He built houses. He advocated for the poor. That’s what I’ve started to do.”

But on Jan. 4, 2019, officers from the New York Police Department’s 13th precinct approached Mishefski in Manhattan’s Union Square Park and sent him to Beth Israel hospital — stating that he was a harm to himself or to others.

Because it wasn’t an arrest, the officers didn’t run his name through their system. If they had, they would have been required to process his possessions. Instead, they threw them all out, including his carpentry tools, citing bedbugs.

Mishefski was released from the hospital a few hours later. He went to the precinct to retrieve his belongings. When they told him it had been thrown out, he suffered a mental and physical breakdown — crying, coughing and spitting at the officers.

Mishefski was released from the hospital a few hours later. He went to the precinct to retrieve his belongings. When they told him it had been thrown out, he suffered a mental and physical breakdown — crying, coughing and spitting at the officers.

Mishefski and other queer youth who live on the streets are routinely misserved by the systems ostensibly designed to address their needs. Their modes of survival are often criminalized — resulting in an overrepresentation of queer homeless youth in the criminal justice system.

The LGBTQ community’s rate of interaction with police is significantly higher than that of the straight and cisgender population. According to a 2011 report by the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, queer youth and young adults were 53% more likely to be stopped by the police, 60% more likely to be arrested as minors and 90% more likely to have had a juvenile conviction.

After years of trauma at home, in foster care shelters and run-ins with the police on the streets, Mishefski had nowhere to turn but inward. Like other queer kids with similar challenges, his solution was to become self-sufficient. And after the NYPD tossed his stuff, even that failed.

A broken home

Mishefski had a stable childhood living with his parents and sister outside Wilkes-Barre, Pa. When he was 7, his parents divorced. His mother stopped letting his father visit them, which broke down the father-son relationship.

They moved in with Mishefski’s grandmother, who had a positive influence on his upbringing. “My grandma was the only person in my whole family to believe in the man I can be,” he said.

Photo by Niamh McDonnell

Matthew “Fire” Mishefski’s backpack contains most of his worldly possessions.

But that influence was short-lived.

Mishefski’s mother decided she wanted to move out. Two years later, she had gastric bypass surgery, the aftermath of which brought her a lot of pain. She developed an addiction to the pills doctors had prescribed.

The surgery left her unable to work, and she became eligible for Social Security disability. She discovered she could earn additional money by declaring her son disabled as well. He was then able to receive Social Security benefits while undergoing pharmaceutical treatments.

Mishefski said his mother made him “a pharmaceutical guinea pig.” He was taking 2,000 milligrams of lithium a day. He was diagnosed with “bipolar disorder, paranoid schizophrenia, severe crippling anxiety — a large part of it was literally side effects of the medications.”

The abusive upbringing Mishefski experienced is common among queer homeless youth. A 2012 study from the Williams Institute at UCLA found that 54% of LGBT youth who were either homeless or at risk of being homeless had a history of physical, emotional or sexual abuse at the hands of their families.

The last time Mishefski talked to his mother, he was 15 and living in a psychiatric ward. When they spoke on the phone he could tell something was wrong. Two days later he found out she had fatally shot herself as she stood over his great-grandmother’s grave.

Life in foster care

Mishefski left the institution and moved in with his father, the first of many times the two would try to live together. The house was in disrepair — whenever he stayed there he would help clean it up, but the living arrangement never worked out. “I love my dad, but he doesn’t take care of himself,” he said.

He then moved in with his grandmother in Virginia, who was sick with cancer at the time. Her illness kept her from being able to take care of Mishefski, so she eventually gave up her custody rights and put him into foster care. The state of Virginia wouldn’t allow him to emancipate because of his history with prescription medications.

Mishefski’s situation is typical nationally. Queer youth are more than seven times more likely to be placed in a group or foster home than straight youth, according to the Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law. Twenty-three percent of LGBQ children in the juvenile justice system had been previously placed in a group or foster home compared to only 3% of straight youth.

Life in foster care wasn’t any easier for Mishefski. He recalled: “My foster parents don’t care about me. They kick me out from 9 to 5. They don’t feed me good. I’m not really a part of the family. So it wasn’t a good relationship.”

Mishefski’s experiences may have a long-lasting, potentially traumatic effect on his life, according to Dr. Violette Hong, a child, adolescent and adult psychiatrist in Berkeley, Calif. “Humans are hard-wired to want to be loved and accepted,” she said. “This need is especially strong during adolescence, when teens are trying to figure out who they are, who they want to be — they do so through the relationships they have.”

Rejection at a young age can drastically alter the mental health outcomes for LGBTQ youth. A recent survey done at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, referenced by the Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College, found that 10 out of 13 participants — mainly queer and trans women — suffered symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, though only two had been diagnosed.

Homeless in New York City

Mishefski eventually aged out of foster care and spent the next few years bouncing around between New York and San Francisco, living with his sister and various roommates. He also lived with a few “sugar daddies,” one of whom was a high-powered tech executive with a penthouse apartment.

He did whatever he had to do to keep a roof over his head. Youth who have faced similar circumstances tend to do the same. A 2015 research report by The Urban Institute notes that in New York, the overwhelming majority of youth who engaged in survival sex had prior child welfare involvement — 75% had previously been placed in foster care.

In May 2017, Mishefski decided to move back to New York and enter the city’s shelters. He would spend over a year in the system, watching his housemates snort coke, smoke crystal meth and shoot heroin.

“The drug is the only good thing in their life,” he said. “That’s their release, that’s their escape from the life they’re given by the system.” The system “is the cause” of people’s suffering, he said.

Mishefski felt unsafe as a gay man in the shelters, having almost been killed at one point. Once he decided to leave, “… I wasn’t going to settle for less. It was the single best decision I ever made.”

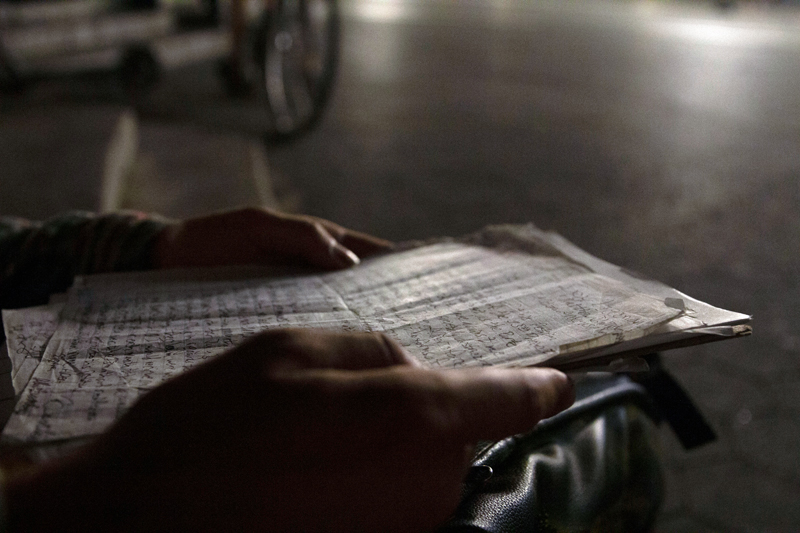

Photo by Niamh McDonnell

The handwritten claim for destruction of property that Matthew “Fire” Mishefski plans to file with the New York Police Department.

In an attempt to tackle the dangerous situations Mishefksi and others find themselves in, Mayor Bill de Blasio recently unveiled the HOME-STAT initiative, an effort to divert the homeless into the city’s shelter system. The pilot program allows multiple city agencies to coordinate and provides new options for the homeless. Instead of receiving summonses, people who commit misdemeanors in the subways will now be offered access to supportive services.

According to the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, the homeless outreach team will consist of licensed clinicians and psychiatrists offering first aid, substance abuse resources, medical and mental health referrals and blood pressure and diabetes screenings. The initiative has gained the support of major criminal justice reform organizations, including The Fortune Society and The Osborne Association.

But Mishefski envisions an even bolder approach: a system where one individual gets back on their feet with the help of a mentor. That person then pays it forward to two more homeless people in a chain reaction. “Here’s a mentor, here’s an investor who’s willing to work with you in the field you decide on, and here’s the connection with the networks that will help lift you up,” he said.

Fighting for justice

Mishefski still lives in Union Square Park. He is suing the city for the destruction of his personal property at the hands of the NYPD. His 10-page claim, which he wrote by hand, seeks $1.4 million in damages. He said he could have a $15 million lawsuit if no settlement is reached.

“Justice comes from the things we do for each other to make the hell we live in better,” he said. “The system is built to keep people down.”

His current plan is to launch a new initiative to fight homelessness in New York City. “The money I get is going to help lift people up, to give other homeless people the things they need,” he said. “I’m on the road to independence.”