John Drazan

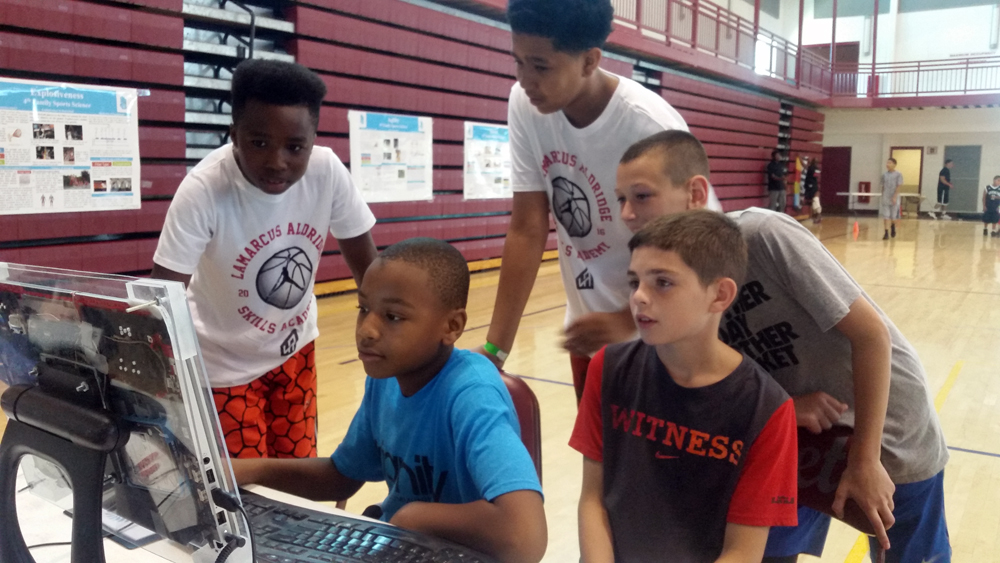

Jason Campbell uses the computer at the basketball court in Albany, N.Y., as other players cluster around him.

The well-meaning cannot parachute into a minority and marginalized community with a remedy for a systemic problem and expect to be easily welcomed. They are an outsider and likely to be viewed as pitching another promise that goes nowhere. Same old, same old.

John Drazan, on the other hand, landed in urban Albany, N.Y., with connections and a basketball. Drazan, who is 6 foot 8 and played college basketball, also had a smattering of the city lingo: “That shot is broke” when a player misses too many shots; you “cook” somebody on the court when you score at will. He was also close with a community leader.

So when Drazan devised an analytics program around hoops in 2012 to get kids in the 4th Family after-school program interested in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math), the kids rallied to him; they paid attention.

“There is this entire cohort of people who want to help marginalized kids, but they don’t have a way to engage with them, or they don’t have the connections to the community,” said Drazan, 29. He’s white and grew up in the more privileged suburbs of Albany.

“Basketball is beautiful because it is something these kids intrinsically understand,” he said. “They can use data to understand and inform their own performance in a game. They might say ‘Oh, that shot’s broke.’ It can turn into a dialogue using science and math.”

Drazan’s work scored a major upset at MIT’s Sloan Analytics Conference in 2017 when he won first prize for his research paper on linking basketball to his STEM curriculum at 4th Family. His presentation at Sloan was centered on “heat maps”: 4th Family children shot the basketball from different spots on the floor and charted their success, or failure, for statistical research. In another class, he had children build a “force plate” out of $50 worth of materials and used it to study, among other things, standard deviation.

Program founders imported him

His methods aroused the curiosity of the children, ages 5 to 18. One ambitious child took 140 shots, and told Drazan he missed more shots than he normally would have. What happened? After a brief discussion with Drazan about sources of experimental errors (the child grew tired taking so many shots), he ran around the gym telling his peers, “experimental error, experimental error, I need a redo.” It was a scientific expression he might not have otherwise used.

“We tap into local community networks and deliver culturally relevant content to the kids,” Drazan said. “No matter how marginalized a community is, there are typically a ton of youth sports programs and there are lots of sports networks that have buy-in from the community. And they happen at local cultural organizations like the YMCA, Boys & Girls Clubs or rec center. Almost all kids are within walking distance of these places.”

John Drazan

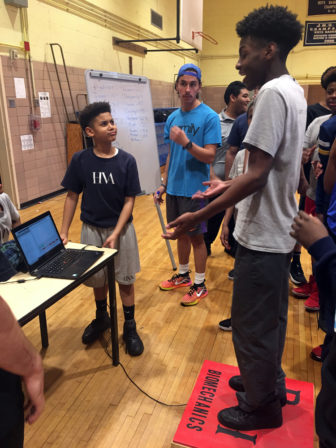

Students participating in the 4th Family after-school program class on STEM and basketball debate the results of an experiment using the force plate to measure vertical jump.

Drazan was introduced to 4th Family by his friend, John Scott. It was Scott and Jahkeen Hoke who co-founded 4th Family in 2012 and greased the path for Drazan into the city community. Drazan is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania; he still works on curriculum for 4th Family pro bono.

Hoke, the chief development officer, came up with the concept for 4th Family while a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta in 2009. The organization’s name is derived from the hierarchy of the African village. Your first family are parents and sisters and brothers. The second family are your grandparents, uncles and aunts. The third family are cousins. Your fourth family is the community.

It took high achievers and insiders like Hoke and Scott, who each have three jobs, to build the trust and get the traction the program needed in the community.

“For me, growing up there was a sense of community, and I don’t see that anymore,” Hoke said. “That’s what is missing in inner cities, that sense of community. We are building this entity to be some of what is missing.”

Hoke and Scott brought Drazan in to specifically provide the missing STEM piece and erase the stigma that minority children cannot succeed at math and science. The U.S. economy is going to be tied to technology and computers and there is a danger, Hoke said, of whole communities being left behind and made even poorer because of a lack of access to tech education.

“Minorities are getting completely obliterated at the job level and down to educational level as far as STEM,” he said. “Investments are being made in suburban districts, and inner-city areas are not getting similar benefits, or even access to the training. Government around education is too slow.”

From the court to the lab

Meeting children where they are with basketball can close the gap. The force plate Drazan helped the children build showed them how to convert “force” into inches, which can be used to measure a vertical jump.

“So now that they are taught what force is you take them into a high school physics course and you see how much more engaged they are,” Hoke said.

What is just as distressing for inner-city communities is not being able to feed the ambition of children who have an appetite for math and science. How many children who want the STEM training are simply left behind and have no chance to reach their potential?

Hunter Best, 20, was almost one of them.

Courtesy of 4th Family

Students at the 4th Family after-school program gather around John Drazan for a lesson linking basketball to science and math. The 6-foot-8 Drazan, a former college basketball player, helped introduce STEM through basketball to marginalized communities in the Albany, N.Y., area.

He first met Drazan through 4th Family when Best was 15 and involved in the after-school program. Best said he is naturally drawn to math and science, but he feared there could be a limit to how far he could go with his education because of finances. His achievement level had to improve so he could attract academic scholarship offers, and that happened with tutelage from Drazan. It started with basketball. Then Best began meeting Drazan in the lab at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) after school, his intellectual curiosity was fed and he achieved.

Best is now in his third year studying mechanical engineering at RPI, a top math/science university in Troy in upstate New York.

“When I first started working with John in high school he would give us papers with this diction and language and I had no idea what I was reading; it was like another language,” Best said. “How do I find the information in the paper and digest it? How do I grasp it? He helped me learn how to wrap my head around big information that I had not been exposed to. I would not be at RPI without him.”

Best marvels at how it has changed the culture around the after-school program.

“I see kids that look like me every day coming through the 4th Family program and being more confident about math and science,” he said. “If you look at the STEM pipeline there are not many minority kids going into this field. A lot of it is how children are incubated at home in under-represented communities. We don’t talk about going off to school and being an engineer. We don’t talk about plans for the future and what it takes to be successful.

“To be someone who looks like these kids and came from where they came from it shows, one, it is possible to achieve in STEM fields and, two, they can do anything they put their minds to.”