Photos by Ryan Kelley

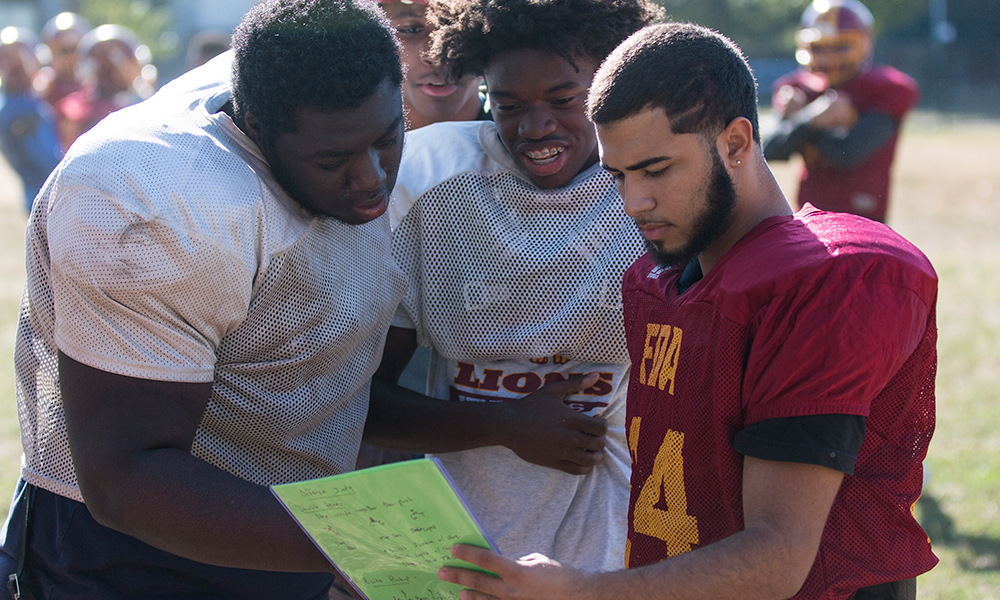

The Frederick Douglass Academy Lions of East Harlem at practice in 2017.

NEW YORK — The weight room inside Frederick Douglass Academy in East Harlem, New York is nothing more than a repurposed classroom. The ceiling is missing tiles, one of the doors has no knob and there is a large, paintless patch of wall where a chalkboard was ripped off.

It has seven cable weight machines, a handful of benches with torn leather seats, one pull-up bar and one squat rack. Two large mirrors on either side of the room make it seem bigger, but they become fogged over in minutes when the room is full of sweating bodies. The varsity team has half as many players as a typical football team, and still they struggle to fit inside.

It has seven cable weight machines, a handful of benches with torn leather seats, one pull-up bar and one squat rack. Two large mirrors on either side of the room make it seem bigger, but they become fogged over in minutes when the room is full of sweating bodies. The varsity team has half as many players as a typical football team, and still they struggle to fit inside.

This is where the Lions will begin their school days, twice a week at 7 a.m. when spring training begins on Monday. These days will prove to be pivotal if the team hopes to accomplish what past teams have; two championship game appearances in four straight playoff runs.

With a much younger roster in 2018, the task seems daunting. But a shoddy weight room is only the beginning. Football is never a guarantee here.

Football Dreams

It was the moment every high school football player dreamt of.

The first round of the playoffs, when winning meant another chance to move on and play for a conference championship. Losing meant the season was over, and the seniors would never represent their school on the field again. For some, it would likely be the last game they ever played.

The dynamics of this extraordinary, heart-pounding, all-or-nothing moment were about to play out, as they do every fall season all over the country, for two New York City teams in particular at Alfred E. Smith High School in the Bronx on a sunny November 2017 afternoon. On one side of the field were the Seagulls of McKee-Staten Island Technical High School, a perennial playoff team filled with mostly white players. Their opponents, the Lions, could not be more opposite. The mostly black team from Frederick Douglass Academy in East Harlem was a newcomer to the conference. Their team was the first independent high school squad to come out of Harlem in more than a decade.

There was a palpable tension in the air, not least because the Seagulls stepped onto the field in a cloud of foregone-conclusion swagger. At least that’s how it had felt to the Lions when, a week earlier, Seagulls coach Anthony Cialdella seemed to suggest in an interview with SIlive.com that he was barely thinking about this first-round game. Cialdella noted that he couldn’t wait to get another crack at top-ranked Lehman High School, who beat McKee by one point earlier in the season. The Lions didn’t even seem to be on his radar.

The Lions’ 30-year-old head coach, Andrew Kell, had read Cialdella’s comments. He made sure his players knew about them.

It led to fury of action as the teams clashed on the field. Their emotions ran high, and so did the score. It was a back-and-forth exchange of touchdowns in a total offensive shootout, and when the clock ran out in the fourth quarter the score was tied, 28-28. Overtime.

Quarterback Domingo Garcia Jr. throws a pass during a game against Sheepshead Bay.

“Men, this is gonna take as much focus as we’ve ever had right now,” Kell said to his players before they ran back onto the field. “Can we step up and make plays?”

“Yes, coach!” his team responded.

Kell raised a fist and his players reached their hands toward it as they huddled close and shouted the same chant that carried them all season. “1, 2, 3, Win! 4, 5, 6, Family!”

FDA got the ball first and the Lions answered their coach’s call to action. A mix of run and pass plays drove them down inside the five-yard line with ease, and a play-action touchdown pass capped it off. They elected to kick the extra point, however, which is less common than going for two at this level. On the snap, the McKee linemen got a great push into the backfield and blocked the kick. But FDA led the game 34-28.

When McKee got its turn the results were similar. A few run plays broke off chunks of yardage until the team was on the goal line once again. After the running back punched in the tying score, he turned right back around for the next play. The score was 34-34, and McKee was going for two. For the win.

One more stop was all the Lions needed to prolong the game. They already stuffed McKee on the two-point conversion earlier in the fourth quarter that kept the score tied. Then they made a goal line stand as time expired to send the game to overtime. One more. That’s all they needed to keep their hopes alive, against all odds.

Running back Mamadou Meiti carries the ball during a game against Lafayette.

On Paper, They Didn’t Belong

The fact that the Lions ever made it to that field with McKee is a testament to how talented they were, because everything else surrounding the team said they didn’t belong.

Six weeks before that game, a typical Wednesday practice began as the players left their final classes and walked into the locker room. The first thing that hit them was the stench of sweaty shoulder pads. Then they greeted each other and the room quickly filled with commotion. Laughter, shouting and conversations about girls were met with the slamming of lockers and click-clack of cleats on the floor. A portable speaker blasted songs by Lil Uzi Vert and everyone started dancing while getting dressed.

Eighteen-year-old Rajay Channer, a senior and captain of the team, was one of the first to break free from the party. He stepped out the back door into the warm fall air with nothing but concrete in front of him. There was no football field in sight.

Rajay Channer (left) leads a group of his teammates on thier walk to the practice field.

The school was surrounded by a parking lot and enclosed by a chain-link fence. Channer walked around to the front of the building onto Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard. He stood at 5-foot-10 and 200 pounds, with his practice jersey pulled up and tucked under his shoulder pads to create a crop top that revealed his muscular core. His teammates followed in scattered groups, with two players pushing shopping carts filled with equipment bringing up the rear.

Seven blocks to go

Rajay Channer was always on the field for the Lions in 2017. On offense, he carried the ball 21 times for 295 yards and three touchdowns. He also caught three passes for 90 yards and one touchdown. On defense, he tallied 28 tackles, one sack and one fumble recovery.

It took the team about 10 minutes to walk the half-mile through Harlem streets, turning heads as they passed by pedestrians. Channer’s jersey had the school’s burgundy and yellow colors, but only two-thirds of his teammates had them. There weren’t enough to go around. The others used whatever jerseys their coaches could scrounge up. Many of them wore gym shorts instead of football pants. Channer had a matching helmet with roaring lion heads on either side, but others had white helmets that had been spray painted burgundy and yellow.

Channer talked about what happened the previous weekend, when the Lions lost their second straight game, something that hadn’t happened in three years.

Damien Contes was the Lions’ full-time strong safety, racking up 25 tackles and two interceptions during the 2017 season.

“I feel like we needed to lose those two games because they felt entitled, and everyone is just really complacent,” Channer said of his teammates. “It goes to show that if you’re not really working hard to get that W, you’re not going to get it. The two teams that beat us? They’re not better than us.”

Their destination was Col. Young Playground, a public park at the corner of 145th Street and Lenox Avenue. The outfield grass in between four softball fields was where the Lions called home. It was more dirt than grass really, and on a warm, dry day a cloud of dust hung in the air throughout the practice. The ground was lumpy and unforgiving, rolled ankles were a daily burden, and rainy days turned the poorly drained field into a swamp. The path leading from the sidewalk to the field was referred to as “the gauntlet” by assistant coach Dennis Vanella. To the right, a pair of middle-aged men passed a blunt as the marijuana smoke slowly drifted toward the team. To the left, a homeless man was passed out on a park bench next to the dugout where the team walked onto the field. “If we’re all going to suffer together, we’re going to make sure that it makes us a lot stronger,” Vanella said.

A cloud of dust rises as the Lions run sprints at the end of practice.

Once the Lions were on the field, that sentiment became clear. The team was made up of kids from every part of the city with vastly different backgrounds and personalities. Senior defensive end Shaquille Stewart rode the subway for an hour and a half every morning to get to school from his home in East New York, one of the poorest neighborhoods in the five boroughs. Senior quarterback Domingo Garcia Jr. grew up without his father, who was in Nicaragua until he could legally immigrate to the United States. Senior strong safety Damien Contes’ grandmother was murdered in the Bronx nearly two years ago. Sophomore lineman Atari Felton was “gang-banging, smoking, and fighting” until he was able to use sports as a way out.

Yet despite their hardships, the FDA Lions have built one of the most successful football programs in New York City in an incredibly short amount of time. Team captain Channer’s first game as a freshman in 2014 was the first varsity football game in school history. It was also the first game of the Jamaican immigrant’s life. The Lions got beaten badly that day on their way to a disorganized 2-8 season. But in the two years after that, the team went undefeated during the regular season, only to lose in two straight PSAL (Public Schools Athletic League) Cup Conference championship games. In 2017, FDA moved up to the Bowl Conference and played against tougher competition.

If the Lions were going to bounce back and make another run to the playoffs, Channer knew he would have to lead by example. “Talking at this point is just pointless,” he said. “We just need action.”

Linebacker Khayier Brown jumps in celebration after breaking up a pass in practice.

No Practice Field, No Problem

Logistics have been the problem for FDA from the beginning. In 2013, it was former FDA principal Joseph Gates who was inspired to start the team, even though he had no field and no equipment to work with. At the time, the Public School Athletic League hadn’t approved a new football team in six years, Gates said. But several students had told him they wished they could play football, and as a former player he knew “it’s a good way to build leadership qualities and a hard work ethic.”

Now he needed the right coach.

Gates sifted through a stack of 300 resumes, he said, and Andrew Kell’s rose straight to the top. Here’s what Gates saw: a New York City Teaching Fellow, who earned his master’s degree in education; a former wide receivers coach for Nassau Community College; a former assistant coach for South Side High School in Rockville Centre, New York; a former player for the Milano Seamen of the Italian Football League in Italy, where he led the league in receiving; a graduate of CW Post – now called LIU Post – where he played wide receiver for two years; a graduate of Nassau Community College, where he also played wide receiver for two years; a graduate of South Side High School, where he played wide receiver and defensive back.

When Kell, 30, got the call for an interview, he had already accepted another teaching position in East New York. He had never been to Harlem before and knew nothing about it, he said. But having the chance to start a football team from the ground up intrigued him enough to give Gates a chance.

“He just sold the heck out of it,” Kell said. “I was in right away. I called the other school as soon as I got out of the building and said ‘Listen, I’m taking another position.’”

Gates was able to sell it to the PSAL too, which he says was the biggest challenge in getting the program off the ground. He negotiated with Alfred E. Smith High School, just over the Harlem River in the South Bronx, which allowed FDA to play home games on its field. Gates did that himself before ever presenting the idea to the PSAL, and continued to put other pieces in place. By the time he approached the PSAL, Gates said he had such a complete plan that the league allowed FDA to skip the developmental season that new teams normally have to play.

Damien Contes (right) goes over the plan for the upcoming game with Charles Johnson (center) and Aboubakar Diakite (left).

Now they just needed players. They started small, only putting together a junior varsity team of freshmen and sophomores, and the first day of summer workouts was held inside the school gym. Kell took the train to Harlem from Rockville Centre, and when he walked into the gym he faced a harsh reality.

“I mean, the kids had no idea,” Kell said of their football knowledge. “We have to teach these kids how to tie their shoes before they can do anything else.” He was joined by assistant coach James Bramble, an earth science teacher at the school and former college football player, and James Llewellyn, a social studies teacher. For the next few weeks they met in the gym every day to see who could even throw or catch a football. Once the season started, Gates would join the coaches as they walked across the 145th Street bridge to practice at a small field at South Bronx High School.

Even with the lack of experience, the coaches figured out positions for every player and focused on the fundamentals. The results shocked the entire school, which Kell says came in large numbers to support the team at its first game against KIPP NYC, where the Lions won in convincing fashion. And they didn’t stop winning. FDA went on to finish the season 7-1.

Kell moved up to become the varsity coach, but the season was filled with turmoil and added another layer of adversity that would prove to be an ongoing challenge. With seniors now able to join the team, many of them faced a new level of accountability in the classroom. Before FDA’s first varsity game, nine seniors were determined to be ineligible, Kell said. They nearly had to forfeit the game. Channer started at linebacker as a freshman, but left the team after that game because his grades were dropping too.

Charles Johnson played on both sides of the line, but was a star at defensive tackle. He led the team with 11 sacks on his way to 40 tackles and two fumble recoveries, returning one for a touchdown.

Even so, the foundation was in place because of players like Frederick Courvoisier. A senior who had never played football before joining the team for that first season, Courvoisier, now 21, committed himself to Kell’s ideals and at the end of the season was awarded as the most improved player on the team. He has since gone on to attend New York City College of Technology and attributes much of his success to what he learned from Kell.

“The first time I met him I was amazed at his football IQ,” Courvoisier said of his coach. “At practice he gets on us because we have to be perfect … Off the field he’s a funny person though. He helps you and he’ll be there for you.”

Variotho Nicolas or “Philly,” as his teammates call him, was a solid two-way player as well. On offense he carried the ball 17 times for 153 yards and one touchdown, and on defense he tallied 26 tackles in 2017.

And Courvoisier has been there for Kell, returning every year since graduation to either watch the games or keep track of the team’s stats for his coach. That’s the most rewarding thing for Kell, he said, to be able to see his players in college and come back to support where they came from: “We don’t want to just be a football team. We want to be a program.”

Winning is the other part of building a real program, and that’s exactly what the Lions started to do the following year. During the offseason Kell saw a new level of commitment from his team, he says. They spent the spring semester working out after school and working harder in the classroom. Channer improved his grades enough to return to the team. FDA also hired Kell’s lifelong friend Dennis Vanella to teach math at the school, and the accomplished football player and Army veteran became the team’s assistant coach.

Rajay Channer leads a line of his teammates running in the halls at FDA before a weight room session.

No longer able to use South Bronx High’s field, this is also when FDA started “squatting” at Col. Young Playground, as Kell put it. He applies for a permit every year, but the city has never responded, and nobody has tried to kick them out.

Vanella, 32, brought his disciplinary style with him, but he also relates to his players in a unique way. He was raised in a single parent environment, with his mother on welfare, moving from one apartment to the next in Rockville Centre. He didn’t own a pair of jeans until the seventh grade, Vanella said. His mom was working two jobs, and there were times when he and his brother didn’t have dinner to eat. As a white man coaching and teaching primarily black and Hispanic kids, Vanella said his personal life has been crucial to breaking down barriers between them. But he also uses this as a tool, telling them “School is the way you escape this stuff, and football is the way that you alleviate all of these stresses.”

With Kell and Vanella’s brotherly dynamic and gifted athletes like quarterback Omari Hill, the Lions developed a true identity and won 23 of their next 25 games over the course of two seasons. Hill, now 19, became the school’s most successful football player ever at the time, Kell said, and is now playing football at Morrisville State College. More important than the winning, however, was the culture that was starting to emerge.

“To me the team was more like a family,” Hill said. “We actually looked forward to hanging out with each other on and off the field.”

Two-Point Conversion

The 2017 season hung in the balance as McKee broke the huddle and the center crouched over the ball. FDA packed in to crowd the line of scrimmage; they knew the run was coming. Channer abandoned his middle linebacker stance and dug his hand into the turf next to defensive tackle and fellow senior Will Hooks.

The ball was snapped, and the quarterback dropped back to hand the ball to his running back. Using his lower leverage, Channer crashed through a gap in the offensive line but got clipped just enough to get taken to the ground. As he fell, Channer turned his head to see the running back, just out of his reach, break an arm tackle and power into the end zone.

McKee beats FDA, 36-34.

The Lions were overcome with emotions when they realized their season had ended so abruptly. Channer lay on his back motionless, staring up to the sky in disbelief for a moment before getting to his feet. Several players dropped to their knees and began to cry, and Channer did his best to gather them to go shake hands with McKee’s players. He didn’t cry, because he knew the Lions have a lot to be proud of.

The season had been a struggle reflective of their environment. FDA started 3-0, then lost two straight games, but won its last four in a row to barely make it into the playoffs.They overcame injuries and players who were ineligible, and whoever was able to take their place stepped up to the challenge. Several Lions also made history along the way.

The Lions struggle through a long round of pushups during a weight room session.

Garcia Jr. threw 26 touchdowns during the season, more than any other quarterback in New York City. He was also the first FDA player to throw for more than 1,000 yards in a season, and he holds school records for most career and single-season passing touchdowns.

Senior wide receiver Austin Messiah caught the most touchdowns in New York City with 16, and he had more than 600 receiving yards. Those were both single-season school records and Messiah is now FDA’s all-time leading receiver.

Junior center and defensive lineman Davon Johnson had 11 sacks on the season, which was a single-season school record and he is now the school’s all-time sack leader. Channer and Shaquille Stewart have set the standard for winning at FDA, with a 30-5 record over their careers.

Perhaps most importantly, Kell said that 12 of his players were on the honor roll that season, and the team’s overall grade average was above 80. Those were both new highs. All of his seniors will graduate, and the majority of them are applying to colleges. This class has the potential to send the most players to college yet, Kell said.

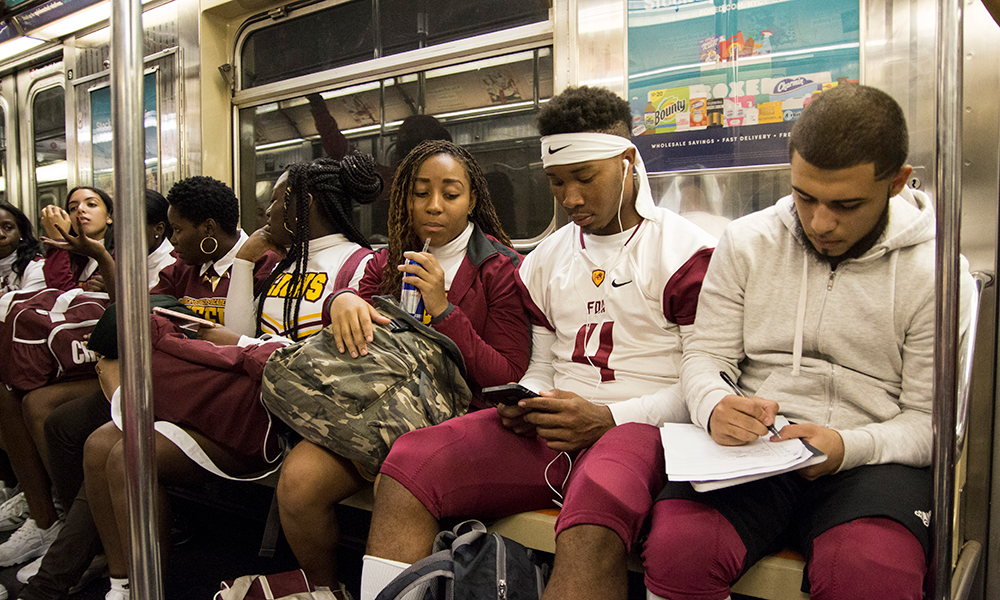

Damien Contes (right) and Variotho Nicolas (center) sit with the FDA cheerleaders on the subway ride to their game against Stuyvesant.

As the team came together in a huddle, wiping away tears and putting their arms around each other, the coaches addressed them for the last time on the field. They talked about how proud they were, and said that nobody should hang their heads because they left everything they had on that field. Then one by one the seniors stood up and addressed the team. Channer, Hooks, Messiah, Garcia and others thanked their teammates and coaches for an unforgettable career.

“I’m not sad that the season is over,” Messiah said, fighting back more tears. “I’m sad that I can’t play with you guys anymore.”

Walking back toward the sideline, Johnson stopped to embrace Vanella, who gave him words of encouragement about next season. For Vanella, those are the moments that have made his time with FDA so rewarding.

“How they put me into that role of being either a role model, coach, mentor, father-figure or brother-figure,” Vanella said. “I never thought of that, I was just being myself and I care about these kids, so I’m going to let them know I care about them.”

The next day, Kell said, he received calls from three other coaches in the city, including Cialdella from McKee, to say how impressed they were that FDA put up such a fight. But for the Lions, that fight is a way of life. Even though they won’t see each other on the field anymore, they’ll hang out in the hallways at school. They’ll go get haircuts together after school. They’ll go to each other’s homes and see each other’s families. They are a family, and for these kids who have nothing but a dirt field, that is much bigger than football.

The Lions warm up on the field at Pier 40 before their game against Stuyvesant

To add to their impressive list of accomplishments as a senior class, six Lions will go on to play football in college: Garcia Jr. will attend Hudson Valley Community College, a top junior college program; Channer will attend Ithaca College; Messiah will attend Buffalo State College; Variotho Nicolas will attend SUNY Maritime; Stewart and Contes are both undecided.