Alex R. Trouteaud

By now you’ve surely heard time and again that, as a nonprofit, it’s critical that you measure your organization’s “impact” so that prospective funders, partners and the like can tell that you are doing good work and are worth the philanthropic investment. Easier said than done, right?

Well, I’m going to show you how ongoing performance measurement is simpler than you may think, can be handled in-house at a relatively low cost and can be empowering rather than punitive for your staff and board.

A little background on why I’m writing this might be helpful. I’m the former executive director of a small to mid-sized nonprofit in Atlanta that focuses on combating sexual exploitation of youth, but I’m also a Ph.D. in applied sociology. Putting numbers on difficult-to-measure concepts is one of my strengths, but I also understand the day-to-day realities of managing/planning/fundraising for a nonprofit.

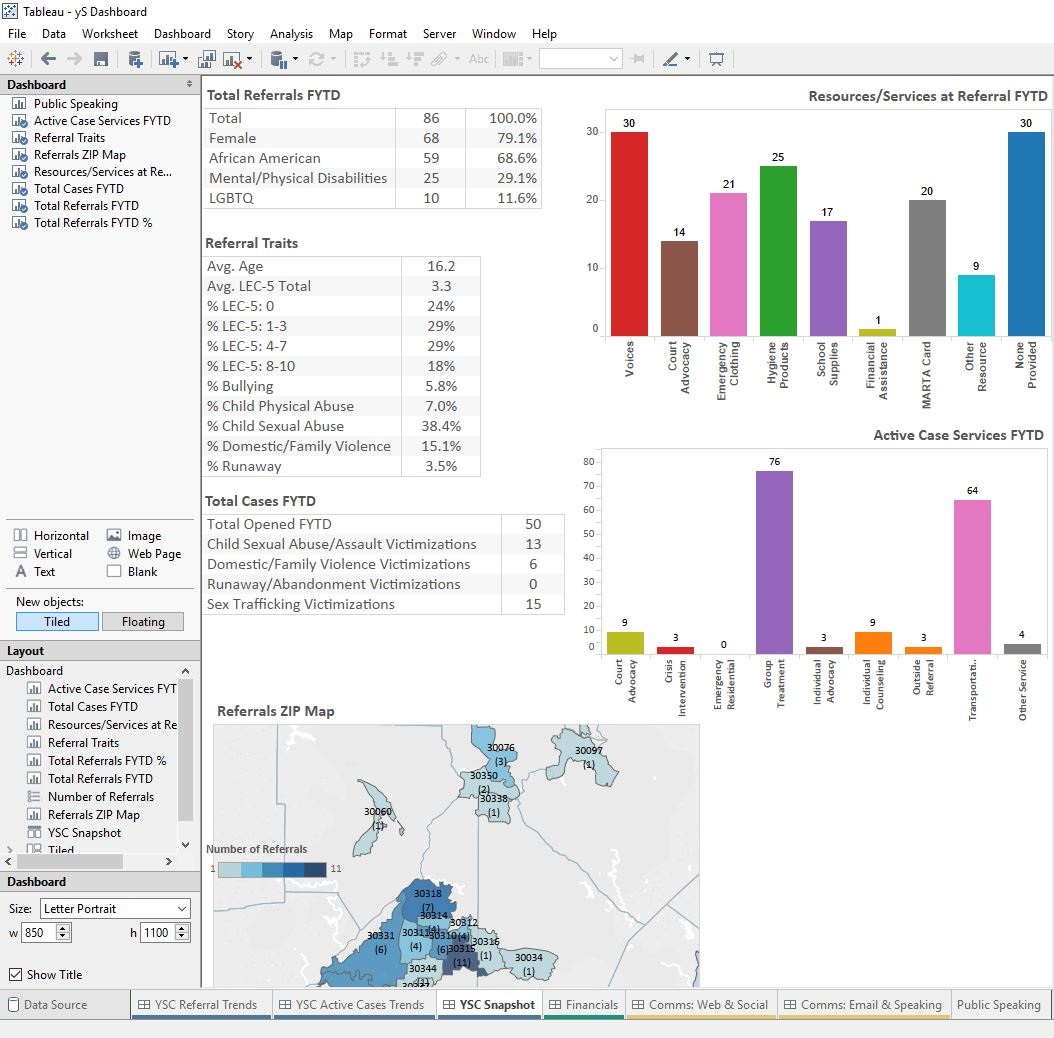

Launching an organizational performance dashboard completely changed for the better how we did our work at youthSpark, from entry-level staff to board leadership. We were able to demonstrate our impact to stakeholders easily and at any time, and we used data as a team to accomplish our mission with clarity and effectiveness. What follows is a guide for how you can lead a similar change in your nonprofit.

You’re Probably Thinking About it All Wrong

When you hear “measuring your organization’s impact,” you might think about: research that assesses the efficacy of your organization’s initiatives, longitudinal data on client well-being, cost-benefit analysis of program investment, or something similarly daunting. These tasks tend to be complicated to design and difficult to execute, and therefore prohibitively expensive for most nonprofits.

To get to that commitment you first need to think about data as a tool for your entire team. Your organization has a mission, and your team must work together to accomplish that mission. Your team includes every staff member, every board member, and probably some other stakeholders too — perhaps volunteers, key funders, government agencies, etc., depending on what your organization’s work involves. People do the work, not the data.

Start the process by finding a small handful of data points that your team tells you will help them as they do their work day-to-day. For example, at youthSpark one of the things we all agreed we wanted to know is how many youths are referred to our Youth Services Center for critical services, as well as some of the key characteristics of these youths referred.

Our case managers needed to make sure they weren’t having to take on more cases than they could realistically serve, I needed to make sure our program strategy was well-fit to our referrals, and the board needed to make sure the organization had enough resources to match the need. This led naturally to agreeing that direct service staff would record certain attributes about youth referred to our center, as well as when and from where they were referred.

Without even touching the question of impact, we agreed that certain data points would help us to support each other, and would therefore be a priority to record and monitor over time at all levels of our organization. Gradually we built buy-in and data literacy by focusing on specific help-me-help-you data points, often over water-cooler conversations instead of boring meetings. No consultants, no worksheets and no top-down pressure.

ABCs That Matter: Actionable, Balanced, Culture

Once you start this process of talking openly and honestly about how your team can use data to support each other, you might be amazed by how it can spiral out of control. Soon team members will dream up all sorts of interesting data points they think might be helpful (“I’d like to know the circumstances behind each trauma our clients experienced, going back at least five years,” “I’d love to know how much funding we’ll get next year,” etc.). Some of these data points might be too difficult or too time-consuming to track, and some might be wishful thinking. That’s OK, though; the hard work of paring down your data wishlist will become easier if you focus on the ABCs: actionable, balanced, culture.

Actionable means the only data you track are the data you can change or that you routinely act on. There’s a difference between “nice to know” and “need to know.” It would be nice to know the circumstances behind each trauma our youth have faced in the last five years before coming to our center, but our clinical staff doesn’t need to know every one of these details to be effective. They do need to know if there is a history of trauma for each youth and whether these traumas have been addressed or not. Similarly, it would be nice to know how many donors plan on contributing next year, but we don’t need to know that to keep doing the work today. No matter how much we love the idea of a data point, before we agree to track it we determine whether it is a “nice to know” or “need to know.”

Balanced means we are collecting a diversity of data points. There’s a management system called the “balanced scorecard approach” that originated in corporate environments to ensure organizations are paying attention not just to financial measures, but also the personnel and customer measures that are necessary to achieve desired profitability and growth.

Nonprofits are always focusing on their financial well-being, but in my experience, staff are more likely to care about data that speak to their mission directly (number of youth engaged, client outcomes, etc.). Therefore, when we put together data points for organizational performance tracking, we need to make sure we include other categories of data such as financial/budgetary performance, marketing/communications reach, volunteer commitments, donor engagement and so on.

Culture in this context means that what we care about above all else is the culture of performance improvement, not the actual data. Relax and just do what’s easiest for right now. Your data are merely a resource for your team to use in helping each other excel. This means you don’t need to worry about imperfect data; over time you will find ways to improve your data if it’s something your whole team really values.

Then, make sure that the data you track for organizational performance is in a dashboard viewable by everyone in your organization — from entry-level staff to board members — because you’re stepping on your own message of help-me-help-you if only some people get to see the data. Most importantly, share ownership of your performance data so that the entire team is accountable for all the measures. The focus should be on “how can we all support division/employee X so that measure Y reaches level Z,” rather than “it seems division/employee X failed to achieve level Z with measure Y.”

Only Now Do We Think About Impact

At this point you might be thinking, “All this talk about collecting data, and you still haven’t gotten to the core issue of measuring your organization’s impact!” Exactly. Unless you have an organizational culture that values performance data and processes in place for collecting and reporting on data, there’s no way you’re going to have the means or organizational willpower to track outcomes. But once you do have data in place, it’s just a small jump to get to the question of impact.

Some organizations mistakenly assume that to measure impact, they must measure their desired mission outcomes. Very rarely is this even possible, particularly for organizations that focus on youth. If I run an organization whose mission is to help make low-income youth more employable as adults, I surely cannot wait for years until my client has become an adult to determine whether my organization was doing good work several years prior!

Instead, I use a logic model or theory of change that (ideally) leans on independent academic research: “Studies demonstrate that programs for at-risk youth that involve elements A plus B lead to a C percent increase in adult full-time employment likelihood after five years.” Thus, when my organization decides to track how many (N) of our youth participate in our program involving “elements A plus B,” I know that we’re gaining a C percent increase in adult full-time employment likelihood for N number of youths. According to the logic model, by tracking program attendance, we were tracking impact all along.

Many nonprofits already have a logic model in place, but certainly not all. If you don’t yet have one, then the process I’m describing here of coming up with data points to track organizational performance will likely lead you to realize that you do have one implicitly — though it may need some attention now that you’re measuring it. If you do already have one, then I’ll bet it comes up all on its own in your water-cooler discussions about what measures your team really needs to know to help each other out.

Save Time, Money by Keeping Your Data in Cloud

I’ll end by focusing on sustainability. Nonprofits don’t exist to measure their work; they exist to do the work. Tracking organizational performance is a classic example of “overhead” expense in nonprofits, though if you do the process the right way, you will create more operating efficiencies and therefore reduce administrative resources overall, especially management professional time. Resist the desire to hire a consultant for this work, because it needs to be part of your operating DNA. Embrace the struggle as part of organizational growth and transformation.

It would take me less than 30 minutes to update our organization’s eight-page performance dashboard, which includes more than 20 complex charts and figures. But, it took me two weeks to create the first presentable draft of this dashboard for staff and board members. And it took close to two years to get all the data tracking systems launched and populated with data so that we had something to report on. We were starting from next to nothing, so hopefully, your organization is already closer than ours was.

We moved our client tracking system to the cloud, which just means that all our youth clinical data are encrypted and stored in a secure, HIPAA-compliant server off-site. We enter client data securely via a web portal, so we don’t have to worry about installing expensive, specialized software on any of our computers. Once a month I download a preconfigured report database, which is then read into our dashboard software. Our entire client management system costs only $270 per month, which is a fraction of what you’d pay for specialized standalone software. If you are an ambitious DIY techie, as a nonprofit you can get access to Salesforce for free.

For dashboard software, we use Tableau desktop, which we got through Techsoup.com for only $120. Tableau has a pretty steep learning curve, but it can also save you a lot of time when you need to update data monthly or weekly. Alternatively, you can use a cloud dashboard service like Klipfolio, but you’ll pay at least $40 per month since currently there is no special pricing for nonprofits.

Every data source we use in our Tableau dashboard is updated with just a few clicks of the mouse. I mentioned that all our youth clinical data are stored in a cloud service. We also download data from Facebook and MailChimp for social media and email communication tracking, Google Analytics for website usage, QuickBooks for budget tracking, Eventbrite for volunteer engagement, Kindful for donor data, and more. Compared to traditional desktop software, cloud-based services tend to have much more robust “data dump” features, as well as better abilities to talk with each other so that data are shared automatically.

Your dashboard can be as simple or as complicated as you’d like, as long as you stick to the ABCs of what data your track and why. Consider making a move to collecting organizational performance data as part of a one-year or even multi-year plan to improve your organization’s ability to achieve its mission. If you rush into it or just bring in a consultant to do the work for you, you’ll miss all the value of the process. When your entire organization relies on data as a way for the team to achieve its mission, that’s when you start seeing improved mission-related outcomes.

***

Alex R. Trouteaud, Ph.D. is the former executive director of youthSpark. He is currently the director of policy and research for Demand Abolition.