This story was originally published by ProPublica.

Two years ago, Illinois lawmakers tried to help students with extreme needs who had a limited number of schools available to them.

They changed state law to allow public money to fund students’ tuition at special education boarding schools, including those out of state, that Illinois had not vetted and would not monitor. School districts, not the Illinois State Board of Education, would be responsible for oversight.

In solving one problem, however, Illinois created another: Districts now can send students to residential schools that get no oversight from the states in which they are located.

The facility that has benefited the most has been a for-profit private school in New York that’s now under scrutiny by disability rights groups. A ProPublica investigation uncovered reports of abuse, neglect and staffing shortages at Shrub Oak International School as it tries to serve a population of students with autism and other complex behavioral and medical issues. Shrub Oak has never sought or obtained approval from New York to operate a school for students with disabilities, which means it gets no oversight from the state.

The ProPublica investigation further found that some districts in Illinois have abdicated their own responsibility to monitor students’ education and welfare. Unlike some other states, Illinois law doesn’t require districts to visit the out-of-state facilities that students from Illinois attend, and some districts have never visited Shrub Oak. Records and interviews also show that districts in Illinois and other states have not always held Shrub Oak accountable for notifying them when students are injured or physically restrained, even though a provision in some contracts requires that the school let districts know.

Sixteen Illinois students have enrolled at Shrub Oak this school year, more than at any of the other 24 unapproved residential schools that Illinois students are attending. With the school charging $573,200 per student for tuition and a dedicated aide for most of the day — one of the highest price tags in the country — Illinois districts are on track to pay Shrub Oak more than $8 million this year. The state reimburses districts for most of the cost.

More of Shrub Oak’s out-of-state students come from Illinois than from any other state.

One Illinois school district official who lobbied his legislator to fund more residential schools said he now is second-guessing that work.

“I felt good at the end of this that we were able to help pass a law that had a profound impact,” said Sean Carney, assistant superintendent for business at Stevenson High School, north of Chicago. “But I’ll be honest, knowing that this particular state, New York, doesn’t really have oversight of the facility, it kind of squashes my enthusiasm for the efforts I went through to make change.”

In written responses to questions from ProPublica earlier this year, Richard Bamberger, a communications specialist hired by Shrub Oak, said the school accepts high-needs students from across the country who struggle with self injury, aggression and property destruction. He said the tuition rates are reasonable, especially given all the services it provides.

Bamberger also said the school plans to seek approval in New York, though the New York State Education Department and other state agencies say Shrub Oak has not filed applications with them. Shrub Oak has no plans to seek approval from other states that send students there, Bamberger said.

Shrub Oak this week declined to answer additional questions from ProPublica specifically related to this story. Bamberger said ProPublica had not included enough of Shrub Oak’s perspective in the previous story, and said the news organization “has no intention of being fair and balanced with this article.”

“We proudly stand by our staff, passionately care for our students, and value the input and collaboration with both our parents and school districts,” he wrote. The school also posted a message online responding to the previous article and saying Shrub Oak is a “safe, supportive educational placement opportunity.”

Liz Moughon/ProPublica

The farm on the Shrub Oak campus includes donkeys, pigs and goats.

Many Illinois parents specifically requested their children be placed at Shrub Oak, and some took legal action to force districts to pay the tuition. Families, in Illinois and elsewhere, have described their desperation to find a school for children who had been rejected from or kicked out of other schools. They shared their relief that Shrub Oak would take their kids and that the state and school districts, legally obligated to educate all students, would pay the costs.

But in Illinois, unapproved schools like Shrub Oak don’t get the same scrutiny as schools the state approves both inside and outside its borders. For example, unlike in other states, Illinois law doesn’t require the schools to disclose to the state when students are physically restrained. They aren’t subject to financial audits. And they can set their own tuition, unlike approved schools that have to negotiate with the state.

To get state funding for unapproved schools under the 2022 law, districts in Illinois must make some basic assurances to the Illinois State Board of Education. They have to certify that there were no other suitable schools for the student. They also must show “satisfactory proof” that teachers at the unapproved school are appropriately certified. Districts must guarantee that the program can meet a student’s educational needs and provide services such as behavioral support and speech therapy. ISBE also requires superintendents to sign a form that says the district won’t hold the agency liable for “any safety and health concerns” that arise.

“The school district assumes all responsibility for the student,” said Jackie Matthews, an ISBE spokesperson.

Districts, for the most part, have not dug deep into Shrub Oak’s assurances, records show. For instance, they have sent the state board of education boilerplate language from Shrub Oak that said teachers had certification or were on a path to get it.

Community Unit School District 300, northwest of Chicago, has had a student at Shrub Oak since 2022, but its employees have never been there. According to his father, the student has been restrained by Shrub Oak workers on many occasions, and his father is aware of that and OK with it. It was only this week, however, that the district got its first notice that the student had been restrained, a district spokesperson said.

The spokesperson also confirmed that the district has never checked the credentials of Shrub Oak employees who work with its student. The spokesperson erroneously suggested that such checks are conducted at the state level, saying that ISBE reviews Shrub Oak staff credentials, which it does not.

When districts have tried to get more complete information from Shrub Oak, such as the names or credentials of employees who would be working with the students, some have struggled to get answers. Woodstock Community Unit District 200, outside of Chicago, asked Shrub Oak for staffing details after receiving questions from ProPublica, but the district said it never got them.

The district has “requested information from Shrub Oak on more than one occasion that it never received,” an attorney for the district told ProPublica.

Lincoln-Way Community High School District 210 in suburban Chicago got state approval to send one student to Shrub Oak in 2022, after telling ISBE that the student’s teacher would be certified and licensed, as required. About eight months later, after visiting Shrub Oak, district officials told the state that Shrub Oak had misled them about the teacher’s certification.

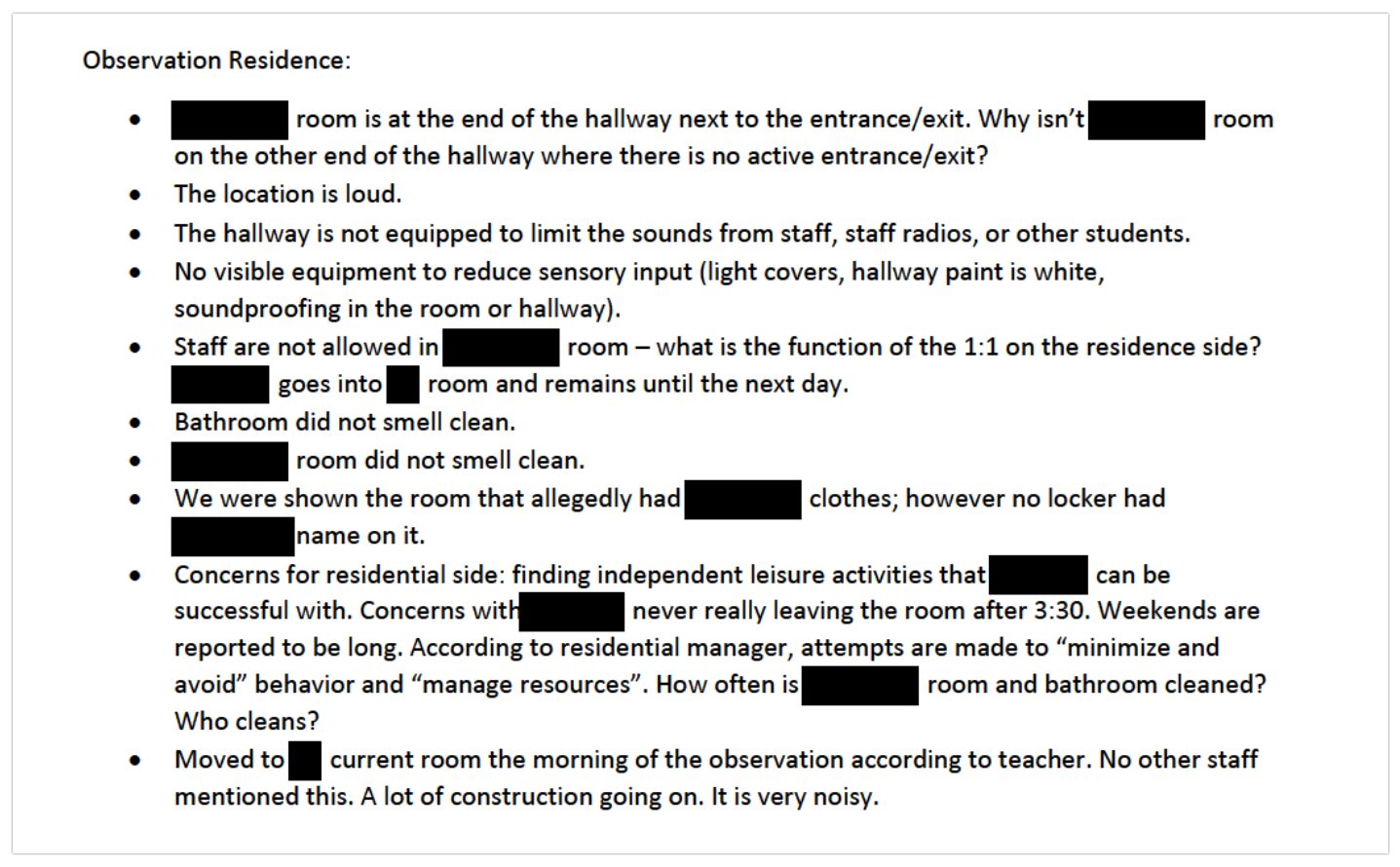

During that visit, district officials identified other concerns, including that “the curriculum is not age appropriate,” the district’s special education director wrote to a state official in March 2023. They questioned whether the student was learning, found he rarely left his bedroom after school hours or on weekends, and noted that his bedroom and bathroom “did not smell clean,” according to district records of the visit.

Obtained by ProPublica

A portion of the notes taken by Lincoln-Way 210 district officials summarizing their observations from a visit to Shrub Oak in January 2022.

After district officials visited again last September and December, they noted in records from those visits that “all was good” and the student “appears to have made progress.”

District Superintendent Scott Tingley wouldn’t say whether he thought Shrub Oak was providing an appropriate education or experience for the student. He lamented the lack of options in Illinois and said parents have asked districts to pay for their children to go to Shrub Oak. Some have taken legal action.

“These aren’t districts that are going out and saying, ‘Here is an option,’” Tingley said. “We wish there were more facilities readily available in the state of Illinois.”

Officials from Chicago Public Schools, which has had three students at Shrub Oak, visited the campus for the first time in December even though, by then, Chicago students had been at the school for more than two years.

The trip came after a Chicago student allegedly was abused by a Shrub Oak worker this past fall. The district learned about the alleged abuse months later from the student’s mother and not from Shrub Oak, which was supposed to report such incidents.

Chicago Public Schools reminded Shrub Oak in September and again in January that it must notify the district after a student is physically restrained by staff, injured or a victim of suspected abuse or neglect.

“This violation of the terms of our agreement is concerning and requires immediate attention,” CPS wrote to Shrub Oak in January about the failures to notify the district.

The contract also requires Shrub Oak to notify the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services of any suspected child abuse or neglect, but the agency has no record of any contact from the school. Shrub Oak told ProPublica that if it failed to notify DCFS, “this was an oversight.”

Chicago school officials said in a written response that they work “to ensure these facilities meet a comprehensive set of criteria and standards.”

The mother of the Chicago student said if she’d had more information, she would have withdrawn her daughter from the school sooner. “That would have made a world of difference. And my child suffered because of it,” the mother said.

Illinois’ scant oversight of unapproved schools troubles Betsy Crosswhite, a Chicago area mother whose son was one of the first Illinois students to enroll at Shrub Oak.

“They are not accountable to anybody. That’s concerning for sure. You have students there who can’t advocate for themselves,” said Crosswhite, whose 17-year-old son went to Shrub Oak for 14 months in 2022 and 2023. She said he had a good experience during the school day but that there wasn’t enough staff during the nights and weekends. He transferred to another school.

She said Illinois education officials should be required to regularly visit the residential schools and examine staffing levels and other operations to protect both students and taxpayer dollars.

Peter Jaswilko’s son, Kyle, was 16 years old when he enrolled at Shrub Oak in early 2022 after months of turmoil. Kyle’s behavior was so aggressive that he spent months, on and off, in a hospital emergency room to keep himself and his family safe. He had been rejected from schools and other facilities. Jaswilko said students like Kyle should have more access to schools like Shrub Oak.

“Illinois is not good at having a lot of resources,” he said. “You can’t imagine what we had to go through knowing there was nothing.”

He is grateful the Illinois law change made Shrub Oak an option, and he said the school has given him hope and his son is thriving.

“I believe they not only saved our lives but are giving our son a chance at a future,” Jaswilko said of Shrub Oak. “When people ask about Kyle, I always say: ‘He’s safe. We are safe.’”

Other states, each with their own oversight rules, also have grappled with monitoring from afar.

Massachusetts acknowledged to ProPublica that it signed off on Shrub Oak as an option for its students two years ago in violation of its own requirements. The state allowed public money to pay students’ tuition there, not realizing that New York has a school approval process — and that Shrub Oak had not sought that approval.

The Massachusetts education department discovered the error last fall and gave the seven districts with publicly funded students at Shrub Oak until July to find other placements for them.

Until recently, the Massachusetts education department also failed to hold Shrub Oak accountable for following a state law that requires all public and private schools to tell the state when students are physically restrained. The department then makes the data public.

The department recently asked Shrub Oak to submit the data so it could “enhance its monitoring” of students there, a department spokesperson said.

Uxbridge Public Schools, southwest of Boston, learned from the mother of a student named Matthew — not from Shrub Oak employees — that the student had unexplained bruises, according to records and interviews. When the district asked Shrub Oak to send details of all incidents, a Shrub Oak official responded, incorrectly, that it did not need to.

“Your contract with us does not state that we are required to send you incident reports,” Lauren Koffler, a member of the family that operates the school, wrote in an email in January 2023, about three months after the student enrolled.

“It was stressful,” Matthew’s mother said. “I felt like we were helpless because the district couldn’t get them to comply.”

Through its spokesperson, Shrub Oak said it “works diligently to ensure it is adhering to individual contracts.”

Matthew left Shrub Oak in October. Uxbridge Superintendent Mike Baldassarre said: “We moved as quickly as we possibly could as soon as we understood there was stuff going on over there.”

***

Jodi S. Cohen is a reporter for ProPublica. Previously, Cohen worked at the Chicago Tribune for 14 years, where she covered higher education. She has been awarded the Worth Bingham Prize for Investigative Journalism and the Education Writers Association Fred M. Hechinger Grand Prize.

Jennifer Smith Richards is a reporter for ProPublica. She wrote about schools and education at newspapers in Huntington, West Virginia; Utica, New York; Savannah, Georgia, and Columbus, Ohio. She most recently worked for the Chicago Tribune.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.