James Steidl, Shutterstock.com

Who will win?

They’re posting on social media. They’re calling and emailing members of Congress.

And after-school providers are talking to parents picking up kids, telling them that funding for programs is threatened.

These actions are in response to the White House budget released in February that would axe federal funding for after-school programs.

Advocates, led by the Afterschool Alliance, are creating something of a virtual camp-out on the doorstep of Congress. Since the beginning of the year, the alliance has tallied 21,000 calls and emails to lawmakers through its website.

Advocates are not happy campers.

Courtney Sullivan

“We feel like we have to do this every time a new budget is released,” said Courtney Sullivan, executive director of the Arizona Center for Afterschool Excellence. “It’s a stressor.”

Paul Morin

Paul Morin, coordinator of the Alabama Afterschool Community Network, prefers to focus on his daily work with kids.

“Why am I having to take part in this battle again when there’s so much that needs to be done for children [every day],” he said.

A feeling of déjà vu

This is the second year in a row President Donald Trump has sought to cut funding for the 21st Century Community Learning Centers, which serve nearly 1.7 million children across the country, mostly in high-poverty school districts. Last year both houses of Congress approved the funding anyway.

But the president’s action worries those who support after-school programs.

Erik Peterson

“We definitely take it seriously and will continue to push back,” said Erik Peterson, vice president for policy at the Afterschool Alliance.

“The most important thing is for [members of Congress] to hear the voices of parents, providers and young people,” he said — to hear that the programs work and are important to them.

“It’s important to get a big push,” he said.

The Afterschool Alliance is also coordinating outreach with large national after-school providers. The include Communities in Schools, After-School All-Stars, Boys & Girls Clubs of America, the National AfterSchool Association, YMCA and the National Summer Learning Association.

For the first time in Peterson’s memory the alliance placed radio ads in Washington targeted to congressional policymakers. The goal is to make sure lawmakers are aware of the value and effectiveness of after-school programs, he said. It sent the same message in a newspaper ad wrapped around the Washington Post in the area around Capitol Hill.

The Afterschool Alliance is working on a Dear Colleague letter showing support by lawmakers, such as the one sent in April last year to leaders of the House Appropriations Committee signed by 81 representatives.

It’s creating an interorganizational support letter that includes national, state and local organizations ranging from PTAs to faith-based organizations.

“We know things like that make a difference,” Peterson said.

The staff in congressional offices look at those letters to see which organizations in their state or district have signed on, he said.

Emboldening after-school providers

In Arizona, Sullivan is speaking to groups to demystify the process of contacting elected officials.

“We put them there,” she said, referring to lawmakers in Congress. “It’s their job to listen and we shouldn’t feel shy.”

She also offers guidelines for advocacy:

The people who work in after-school programs are citizens and can express their view in their own time and own space. If you’re using your own phone, own computer and in your own time, it’s perfectly appropriate to call a legislator, she said.

It is not appropriate to contact lawmakers while using state resources in an after-school program, she said.

Nonprofits, whether after-school providers or other groups, are free to educate but not to endorse candidates or specific legislation.

“Parents can be a huge advocate,” Sullivan said. She tells the staff of after-school programs to let parents know that the latest White House budget has zeroed out 21st Century funding.

Her center has launched a campaign on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

In addition, Sullivan plans to take three people with her — a representative from the Arizona United Way, a community leader and an after-school provider — to Washington on April 19 for the Afterschool for All Challenge, a day that advocates converge on the Capitol.

The lawmakers she’s visited in the past have always been cordial, she said.

They listen even when they say they don’t agree, she said. While federal after-school funding has bipartisan support in various parts of the country, Arizona legislators are divided along party lines.

This is not ‘our parents’ America’

Morin, of the Alabama after-school network, will also be traveling to Washington in April. He has not yet begun an outreach campaign.

“We’ve been so busy with so many other things,” he said, including working on quality standards, professional development and STEM learning

But the former schoolteacher is deeply committed to after-school programs.

“I will never give up the fight because I believe in the importance of funding for after-school,” he said.

“We do not live in our parents’ America,” Morin said.

Today, if a child is fortunate enough to live with both parents, both are likely to be working in jobs, he said. And there are many more single-parent households, he said.

“It’s unrealistic to think that there’s not a need for quality after-school programs.”

Morin noted that juvenile crime escalates between 3 p.m. and 7 p.m.

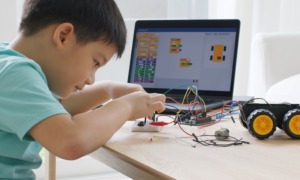

“Why not use the time to engage kids with opportunities?” he said, keeping them off the streets and safe and engaged.

Morin said that lawmakers like Rep. Martha Roby, R-Alabama, understand the need and have visited 21st Century programs in Alabama.

But not all members of Congress from Alabama agree, he said.

“When you are born and raised in affluence, you may find after-school to be irrelevant,” he said.

Kids only spend 20 percent of their time in school, Morin said.

“Why not leverage this time frame [after school] to keep them engaged?” he asked.