When the National Juvenile Justice Network (NJJN) held its annual meeting three or four years ago, a representative of one of its 41 member organizations in the juvenile justice advocacy field stood up and pointed out that just about everyone in the room was white and had a professional degree.

When the National Juvenile Justice Network (NJJN) held its annual meeting three or four years ago, a representative of one of its 41 member organizations in the juvenile justice advocacy field stood up and pointed out that just about everyone in the room was white and had a professional degree.

A groundswell of response and interest in addressing that issue of diversity led to the formation of the network’s Youth Justice Leadership Institute, which identifies people of color who have had personal experience with the juvenile justice system and who want to become leaders in the reform movement. At a recent gathering of fellows, 10 of whom are selected each year, the value of recruiting people from diverse perspectives and backgrounds hit home during a discussion about sentencing, said Sarah Bryer, director of NJJN.

“Many folks had, within their own family, people who had been in the juvenile justice system,” she said. “When we spoke about the rubric of sentencing, they were speaking from a place of really deep knowledge about the system. … If we don’t have people who understand it from a personal or community perspective, we will always slightly miss the mark. We will do good work, but not the best.”

Whether in juvenile justice, out-of-school time or other corners of the youth-work field, agencies that serve predominantly African American, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, poor, urban or rural youth can hire a certain contingent of white, middle- or upper-middle class staff from suburban backgrounds and succeed in their missions.

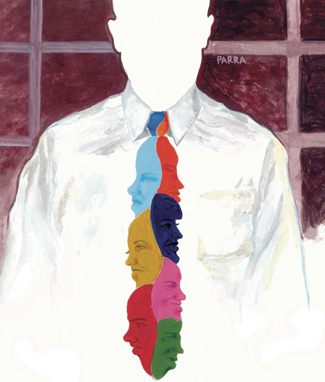

But agency leaders, funders and researchers in the youth field point out if staff becomes too disproportionately different in race, ethnicity and overall background from its clientele, agencies will not succeed as well as they might, if at all. And, they say, agencies that succeed in diversifying line staff but not management and leadership still won’t reach their overall potential.

“It’s a flaw of the movement that so much visible leadership comes from folks who aren’t directly impacted,” said Diana Onley-Campbell, coordinator of the Youth Justice Leadership Institute. “What’s lost is the perspective of being immediately under the weight of that system, which is a perspective that often can bring some urgency to the work that might otherwise be lacking.”

Do Leaders Reflect Clients?

“There is a need for a talent pool of young people of color,” said James Bell, founder and executive director of The W. Haywood Burns Institute in San Francisco, which focuses on racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system. “In terms of management, there are lots of people who are the line staff and are at the lower to mid-range parts of the organizational food chain. But I think as you get higher and higher, the numbers of people of color get lower and lower.”

That thought is echoed by Jimena Quiroga Hopkins, co-director of Development Without Limits West, which provides training and curriculum development around a group of issues, including diversity for after-school and summer programs in the western United States. “More and more line staff do tend to be representative of the communities of young people in after-school programs,” she said. “What’s not happening is the coordinators and directors are not as representative. Now there’s more of an awareness of that: How can we grow leadership of color?”

A diverse workforce helps agencies to navigate cultural differences more smoothly, said Elyse Clawson, executive director of the Portland, Ore.-based Crime and Justice Institute. “We learn from each other,” she explained. “Kids and adults benefit from people of all kinds, especially people who look and feel like they came from similar situations, whether that’s because there are role models or because there’s a sense that people can relate to them. Staff benefits because they learn from each other.”

In deciding to fund the Youth Justice Leadership Institute, the Public Welfare Foundation became convinced of the importance of the juvenile justice reform movement being connected to communities of color, said Katayoon Majd, program officer for juvenile justice.

“We’re ensuring that the advocacy voices are informed by the communities that are experiencing the problem, that have ideas about the solution, that have a greater sense of authenticity and legitimacy,” she said. “It’s hard to do that if you’re not meaningfully engaging the communities that are impacted.”

“This is not … saying you can’t be an effective advocate if you’re not from a community that’s being impacted,” Majd added. “It’s taking a bigger picture and saying: Overall, how does the advocacy field reflect communities, how does it ensure the field has credibility in the communities impacted, how does it ensure that the communities are at the table?”

When LaMarr Darnell Shields, co-founder and senior director of education and innovation at the Baltimore-based Cambio Group, consults with public and private agencies around diversity issues, he finds that some can’t state their mission with regard to diversity and others have a shallow idea of what it means.

“It can’t be something on paper,” Shields said. “It can’t just be, tomorrow is ethnic day, bring in food from your culture. We need to create a board that’s reflective of the population we’re serving, at all levels. We need to focus on an ongoing effort to create a culture of access, inclusion and equity.”

In Search of Diverse Staff

Creating that culture requires out-of-the-box thinking about recruitment, Hopkins said. “Some of the most successful programs actually have a person from the community and use that person as a resource to go out into the community and recruit staff,” she explained. English-language learners are often intimidated, and agencies need bilingual staff to engage them, she added.

National organizations like YMCA and Big Brothers Big Sisters of America say they’re working on a number of fronts to diversify their staff leadership. Figuring that its youth are both a diverse group and potential future employees, the YMCA has launched a couple of efforts to interest teens — including African American, Latino, female and LGBT teens — in careers in recreation.

The YMCA’s Emerging Leaders Resource Network, which now has 2,100 members, provides opportunities for professional development, such as webinars, that provide them with insights into best practices for job interviews, for example. “We have a special emphasis on making sure that young people see the nonprofit sector as a long-term career,” says Lynda Gonzales-Chavez, vice president of national diversity and inclusion. Parallel resource networks more specifically target African Americans, Asians, Hispanics and Latinos, women and LGBT individuals.

In a partnership with Deloitte Consulting, the YMCA has rolled out a targeted initiative called the Hispanic-Latino Road Map, in 35 regional Ys with more than 100 branches, specifically to identify new employees and leaders in a community that’s experiencing triple-digit percentage growth in places like rural Georgia, the Atlanta area and the Carolinas. “My department is always doing the nudges, the pushing and the pulling, making sure that we’re including any areas where we see gaps,” Gonzales-Chavez said.

Similarly, Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS) has advisory councils in the African-American, Latino and Native American communities to advise them and help make connections to potential staff and board members. For example, the African-American council has been working with black fraternities and sororities to recruit volunteers who are people of color. The organization’s chief diversity officer and other staff have coached and trained local boards in how to be more inclusive, said CEO Charles Pierson: “We heard loudly that, ‘We want to do this, we just don’t know how’.”

BBBS undertook research more than five years ago that showed engaging African-American men means being “consistently involved. You have to have real partnerships in African-American media. You can’t say, we’re going to do a recruitment drive, and then go away,” Pierson said. As a result, the organization has had an ongoing relationship with syndicated radio host Michael Baisden.

In the Latino community, BBBS learned through focus groups that the concept of a complete stranger mentoring a child is “not very Latino,” Pierson explained. “We incorporated that [cultural difference] into our model of one-to-one mentoring.” The organization also created a micro-site at www.latinobigs.com to cater specifically to Latino volunteers.

A former juvenile justice director in both the state of Oregon and in Multnomah County, which includes Portland, Clawson of the Crime and Justice Institute said she learned to recruit differently to reach diverse populations. “We had to reach out to both formal and informal leaders in various minority communities and also advertise in ways that, in publications and on the radio … were particularly [targeted] for that community,” she said. “We recruited there and sought guidance from leadership of various coalitions about the way in which we advertised. We needed to use different words sometimes.”

Results on the Ground

When Clawson left Multnomah County in 2001, her executive team was approximately one-third people of color, and her managers overall were to close half. “We provided a lot of development opportunities for all staff and worked at helping entry-level staff who came on as probation or parole officers getting support for learning what they needed to learn and getting the experience they needed to get to be promoted,” she said. “We tried to have diverse staff at all levels, which is as important as getting diverse staff in general.”

The YMCA has partnered with the Bank of America to offer career mentoring to part-time YMCA employees ages 16 to 21 in five cities: Chicago, Charlotte, Kansas City, San Diego and Seattle. They connected 121 mentees to mentors (who included 25 Bank of America employees and other adult professionals) between June and December 2012. Of those 121, 48 interviewed for full-time positions, and 33 (27 percent) obtained full-time employment at a YMCA.

In the year since Pierson became chief executive officer of Big Brothers Big Sisters, he has worked to increase diversity from the executive level down and among volunteer “Bigs” themselves.

“The No. 1 characteristic we look for is safe, caring consistency,” Pierson said. “We know that mixed racial matches can work tremendously well. We’re also sensitive to the parent or guardian’s desire.” He added: “We clearly don’t believe it’s impossible for white mentors to have African American or Hispanic or Native American mentees. We want to make sure that all mentors, regardless of their race, are sensitive to the issues that these kids from all walks of life are facing.”

Getting Kids to Open Up

Pierson uses the term “project-ability” to describe how it can be important for some children to have a Big Brother or Big Sister of a similar background. “If you’re not the same color they are, you’ve got to be able to help them see other role models in their life,” he said, recalling a single mom in central Florida who wanted an African-American “Big” for her son because his father had disappointed him. “She was telling us a wonderful story about the difference the Big Brother had made,” Pierson said.

In the juvenile justice field, Bell, of the Burns Institute asserted diversity among staff in a custody-and-control facility probably doesn’t make much difference relative to the youth being held there, but it makes a significant difference among staff engaged in intervention and services for youth.

“There’s a sense of familiarity,” he explained. “There’s a certain level of comfort that these people have some sense of what I’m talking about or what I’m going through, so I don’t have to put on an act or be somebody I’m not.”

Shields emphasized that hiring and promoting a diverse staff is not just about skin color. “How do we begin to have those conversations about hiring people who can culturally relate to these youth?” he said. “Not just ‘I’m black and you’re white,’ but the neighborhoods they come from. How can we improve customer service? By bringing together the most diverse group of people, not just racially but also a diverse group of ideas. It’s greater than what someone looks like on the outside.”

Connecting with youth also means bringing them into leadership, Shields said. “It’s about showing young people how we pass the baton on to them,” he said. “If we don’t have that voice, we tend to lose out. I can state what the research says and pull data out of my behind, but we need to see young people at the table. They have something to add — not from the sidelines, not an afterthought, but a ‘before-thought’.”

That inspires some to enter the youth field as adults, Shields noted. “When they get older, they know Robert’s Rules of Order,” he said. “They know how to apply for grants. They want to know this. But the adults normally push them out.

Illustration credit: Illustration by S.W Parra/MCT

Ed Finkel is a writer, editor and Web content manager with 20 years of professional experience.