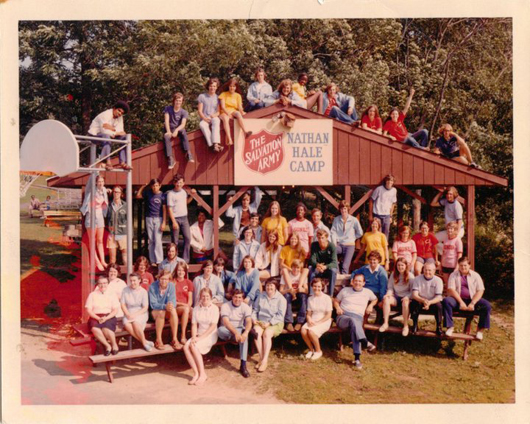

NEW YORK — Peter Carroll’s first love almost cost him his family and his home when he was just a 14-year old boy. Carroll, who is white, fell in love with a black girl named Patricia by the shores of Coventry Lake, Conn., in the sweltering summer of 1974 working as a counselor at Camp Nathan Hale. When his father, Harry Carroll, a child of the Depression and a World War II veteran, learned that his son was dating a black girl, he sent Peter’s older brother to the camp with a stark message.

NEW YORK — Peter Carroll’s first love almost cost him his family and his home when he was just a 14-year old boy. Carroll, who is white, fell in love with a black girl named Patricia by the shores of Coventry Lake, Conn., in the sweltering summer of 1974 working as a counselor at Camp Nathan Hale. When his father, Harry Carroll, a child of the Depression and a World War II veteran, learned that his son was dating a black girl, he sent Peter’s older brother to the camp with a stark message.

“He told me if I didn’t stop seeing her right away that I was going to be disowned from the family,” Carroll said. “Even back then the [Salvation Army] church didn’t frown on interracial dating. They were very progressive. There was no race issue. But at home. At home it was scandalous.”

Facing the prospect of being an outcast from his family Carroll reluctantly agreed to his father’s ultimatum and reassured his older brother that he would do as their father demanded.

He didn’t tell Patricia, 13 at the time, the truth — that he was ending their relationship to acquiesce to his father’s demands. He thought the ugly intrusion of race would hurt too much. So he sat down with a broken heart and a tear-streaked face and concocted a letter about how he didn’t think their relationship was working.

Carroll and Patricia’s “special song” that summer was Elton John’s “Someone Saved My Life Tonight.” He ended his break up letter with part of the chorus from the song:

And Sweet freedom whispered in my ear

You’re a butterfly

And butterflies are free to fly

Fly away, high away, bye bye

It was short lived, but Carroll’s first love, and the camp where he met her, changed the course of his life.

“It absolutely opened my eyes, it was a whole new world,” he said. “It got me to realize there are other places in the world than just little Lincoln, [R.I].”

Camp Nathan Hale was one of many that dotted the rural communities in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Some, like Nathan Hale, were established and operated by the Salvation Army.

Others, like Camp Ellen Marvin, were run by some of the Settlement Houses in New York City, and were animated by political progressive spirit, instead of a religious one. Founded in the 19th Century by social reformers, the settlement house movement brought the wealthy and the poor together to live in a community regardless of race or class.

The camps, which opened as early as the 1940s, are gone now. Part of the land where Carroll and his camp mates spent their summers together is now for sale, dormant. But the life and times of these interracial experimental camps are preserved in a series of photo essays taken by Gordon Parks who later went on to take some of the most iconic photos of the Civil Rights Movement. (A photo spread of Parks’ work appeared in last month’s edition of Youth Today, accompanied by an essay by David Cummings)

Although they were founded for different reasons, the camps stood out for welcoming black and white children to the camp as equals at a time when the country was partly defined by its corrosive racism and formal institutional racial barriers enforced by law. Black and white campers gathered to sing songs, build fires, row in the lakes and join in all the stand-by summer activities that create memories in children that are cherished when they reflect on their lives as adults.

Carroll, 53, is married now, happily, with two adult sons. He lives in Ashburton, a bedroom community in northern Virginia where he works as a software salesman. But after all these years later, he still remembers his first love and how much it hurt when he sat down to compose his first break up letter. He talks about the camp with his wife to this day.

Carroll remembers the trips from Pawtucket, Rhode Island to Camp Nathan Hale. A beat up old Salvation Army church van would collect him and his campmates from the church parking lot and they would trundle to Connecticut. The children would chatter with excitement as they saw the grassy hill surrounded by simple log cabins, a field, where they would compete in softball games, and beyond, Lake Coventry where they would go for swims and dig for crawfish.

Pete Carroll grew up in a former mill town in Northeast Rhode Island called Lincoln. Although named to pay homage to president Abraham Lincoln, Carroll remembers there was only one black family in town when he was growing up and they were treated poorly.

Students at Lincoln High School would whisper barbed jokes, as the black student would pass. Today, Lincoln remains an almost all white town. Carroll said it’s an insular place, the kind of place that if you’re born into, you tend not to leave.

Carroll said his family also felt the coarse, alienating treatment of an outsider, not because of race, but because of religion. Lincoln was a heavily Catholic community and his family was protestant. They would drive over on Sundays to the local evangelical Salvation Army church in neighboring Pawtucket, a poorer town.

He said attending service was a sharp departure from the white faces he encountered on his quiet tree lined streets at home. He said black and white families would mix together in song and worship during the services. Afterward, the children would play together.

“It was almost like a social event,” he said.

While all the children would scamper and improvise make believe games, Carroll stayed away.

“My parents wouldn’t let me hang out with the black kids,” he said. “I was never allowed into the black neighborhoods unless I was going to church. My parents, they were prejudiced. My dad related quite a bit to Archie Bunker.”

He said his father would often joke with neighbors about the racially charged jokes about blacks and others, but he never understood the irony of Archie Bunker’s worldview being out of touch and provincial.

“I’d cringe at the things he’d say watching the show,” he said.

Camp Nathan Hale represented a total break from the conformity of his hometown.

“To me the camp was a completely different world from all that,” said Carroll who attended the camp for four years. “As soon as you were dropped off you could feel it. There was no division of people. I never felt like the odd man out, no one did. It was a world unto itself. I grew up in an all-white town. Here I realized people are just like me. There’s no difference between us, none that mattered anyway.”

Even years later he talks about the camp with a reverence. He said it not only offered him a fun filled summer of outdoor activities and campfire stories, he said it shaped his worldview.

A few years after his first break up, Carroll was back at the camp. He rowed out to the middle of the lake with a friend, a black girl, when his father arrived for a surprise visit. His father was furious. He made a lifeguard get him a motorboat. His father climbed in and sped out to confront his son. When they got back to shore the father and son stormed into a cabin.

“We had it out right there,” he said. “We had a screaming match. Even years later, in my 30s and 40s, he’d bring that up. That was a sore point for me. The camp opened my eyes to the idea of differences of people, not just race, but points of view. It made me realize that you don’t have to think the way your parents think; you can think for yourself.”

Although he no longer attends church on Sundays, Carroll said he gives to the Salvation Army “until it hurts.” Other campers are similarly awed by the camp and credit their time at camp for teaching them lessons as children that are still shaping them today as aging adults.

Last September, Carroll commiserated with his old campmates at a Nathan Hale reunion. In the intervening years his childhood friends had become parents, some grandparents. He had not seen many of them since the Nathan Hale days, but they slipped with ease back into the youthful patterns of their friendship. He even saw his first ex-girlfriend. She was a mother, living in Newport, R.I., and still beautiful, Carroll said.

“She was still very attractive,” he repeated. “Very attractive.”

The two friends remembered old times, even reminiscing over their first break-up. They parted with hugs and promises to stay in touch. But the truth about the real reason for the break-up remained a secret. He couldn’t bring himself to tell her, even after 40 years. He didn’t want to risk hurting her all over again.

Photo credit from the top: Joyce Hodgson; camp staff by Barb Ahrens McLaughlin; campers by Laurie Dunlap.