Prison-to-college initiatives might become more common in United States

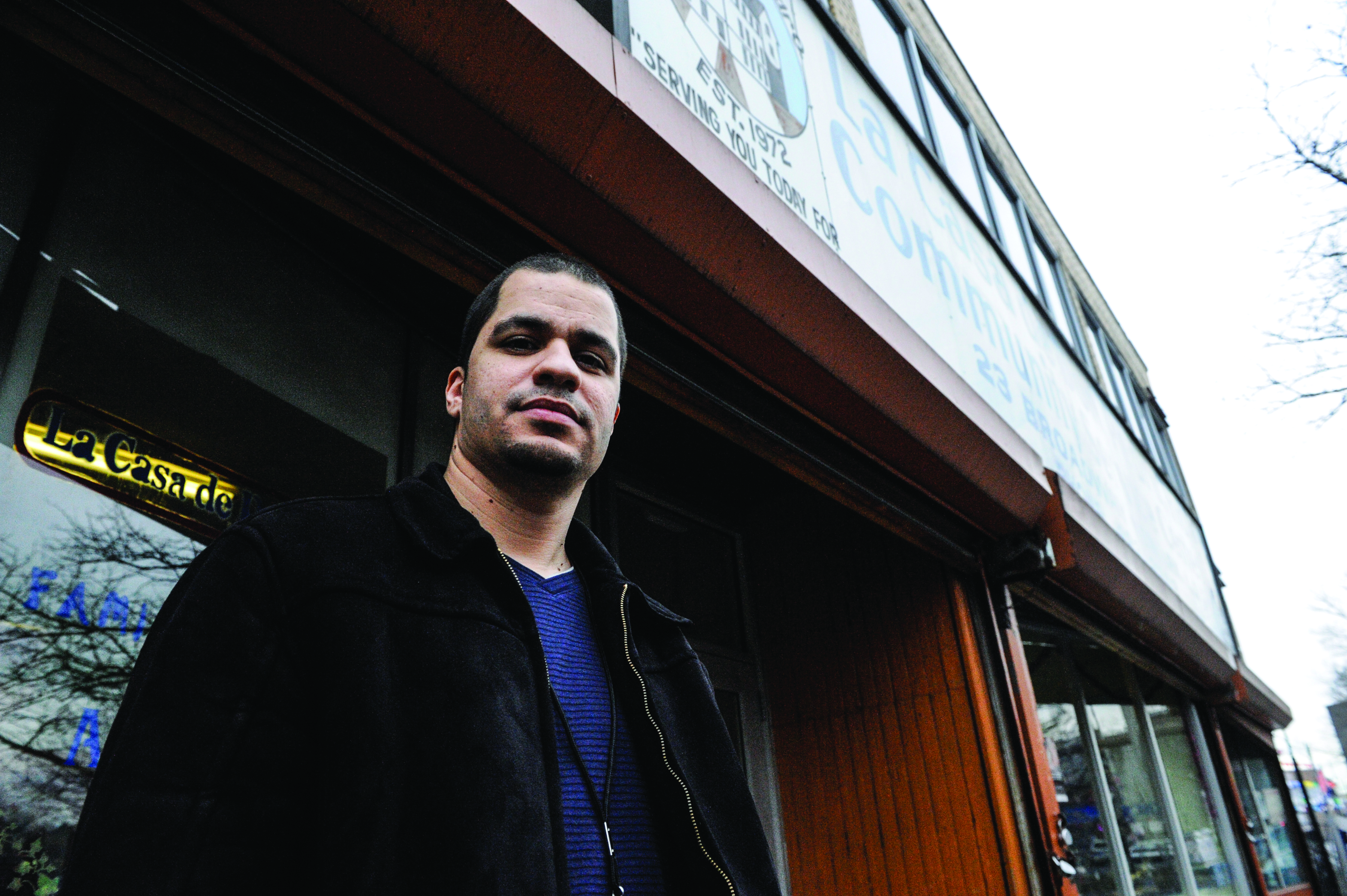

A little more than a decade ago, then-22-year-old Danny Feliciano stood at the front end of a six-year sentence in a youth correctional facility for robbery.

Today, the former inmate counsels young court-referred individuals as a Youth & Family Counselor at La Casa de Don Pedro Inc., a nonprofit agency that provides social services to the Hispanic community in Newark, N.J.

If you ask Feliciano what helped him make the 180-degree turn, after thanking God, he’ll tell you about the Mountainview Program that operates on the New Brunswick campus of Rutgers University.

Though a fledgling program that is currently unfunded and staffed by volunteers, proponents describe it as one of the rare but vital portals that enable current and former inmates to move from the world of corrections to the world of college.

Smoothing the path from prison to post-secondary education, the program provides current and former inmates from the Mountainview Youth Correctional Facility in Annandale, N.J., with academic advisement, advocacy in the college admissions process, and a positive peer group to help them stay the course.

“That kind of seamless link doesn’t exist in any kind of real way, and a lot of research seems to call for it,” said Bianca Van Heydoorn, director of education initiatives at the Prisoner Reentry Institute at John Jay College of Criminal Justice within the City University of New York.

Opportunities on the horizon

Though prison-to-college programs are relatively rare, they could become more common or, at the very least, get additional opportunities for funding during the second term of the Obama administration, according to Van Heydoorn, who attended the U.S. Department of Education’s Correctional Education Summit last November in Washington, D.C.

At the summit, administration officials announced a new $1 million grant program called “Promoting Reentry Success through Continuity of Educational Opportunities” or PRSCEO. Decisions on the two to four grant awardees are expected in February, and more education-based reentry grants are also expected.

“They were pretty explicit about saying this is not the last train,” Van Heydoorn said about the administration’s PRSCEO grant announcement. “There will be more conversation and an attempt at more funding.”

The PRSCEO grant — a collaborative effort between the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice — is seen as a way to increase opportunities for incarcerated individuals as they return to society and to reduce their chances of returning back to crime.

“Promoting effective policies that offer education and workforce training will protect our communities and benefit our economy,” U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said in a statement announcing the grant.

Added U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder: “Expanding access to education is a proven strategy for reducing recidivism and preventing crime.”

The remarks of Duncan and Holder could signify a departure from the past, when — according to a 2011 policy brief — “discussion of postsecondary opportunity for the nation’s prison population is notably absent from the top tier of state and federal policy agendas.”

“This lack of topline policy attention to [postsecondary correctional education] is detrimental to the country — postsecondary education has a critical role to play in mitigating challenging social conditions exacerbated by high incarceration levels,” states the Institute for Higher Education Policy brief, “Unlocking Potential: Results of a National Survey of Postsecondary Education in State Prisons.”

Scholarship on the prevalence of postsecondary correctional education has been “limited,” largely because of a lack of systematically collected data that is comparable across states, the brief says.

Scholarship on the prevalence of postsecondary correctional education has been “limited,” largely because of a lack of systematically collected data that is comparable across states, the brief says.

The brief stated that 35 to 42 percent of correctional facilities offer “some form” of post-secondary education, and that among those who have participated in post-secondary programming, “several positive post-release outcomes have been observed, including increased educational attainment levels, reduced recidivism rates, and improved post-release employment opportunities and earnings.”

Thus, more grant funding for post-secondary opportunities for those in prison could mean more life-changing opportunities for individuals such as Feliciano, who said that before he got involved in the Mountainview Program at Rutgers, he never thought a college degree was an option.

Recruiting students from prison

“I wasn’t seeing college in my future,” Feliciano said. No one in his family had ever enrolled in college, much less finished.

All that changed in spring of 2011, when Feliciano — after struggling through statistics and other math courses — earned a sociology degree from Rutgers, which U.S. News & World Report has ranked as one of the top 100 universities in the nation.

This never would have happened, Feliciano said, were it not for the Mountainview Program at Rutgers.

For Feliciano, Mountainview is where he met Donald Roden, a professor of Japanese history who started the Mountainview Program at Rutgers in 2005 after having spent the previous three or so years tutoring inmates there.

“Once I started volunteering I realized they taught a few community college courses in the Mountainview facility,” Roden explained. “Then the idea dawned on us that maybe we could recruit some students to Rutgers from that in-house program.”

Roden said recruiting from correctional facilities is in line with Rutgers’ emphasis on diversity and its commitment to have the university be fully representative of the state.

Feliciano said Professor Roden’s positive view of inmates is what encouraged them to pursue higher learning. “He seen [sic] that we were pretty much youth that had made some mistakes in their lives, as opposed to being criminals,” Feliciano said, “that if given an opportunity you’ll be able to grab ahold of it and be able to make something of it.”

Feliciano indeed made something of the opportunity that was extended to him. Though he initially worked at a fast-food restaurant after graduation, he landed his current full-time job within five months of earning his degree. Feliciano now works directly with court-involved young people whose lives, he says, closely mirror his own when he was their age.

When Feliciano sat down for a job interview at La Casa de Don Pedro, he was upfront about his criminal past. Thanks to his involvement with the Mountainvew Program at Rutgers, he was also able to confidently direct the conversation to the positive things he has accomplished.

Feliciano said one of his interviewers liked the fact that he was straightforward and “didn’t beat around the bush” when it came to his prior offense. “But what impressed him more was that I did something for myself,” he said.

Early indicators of success

Similar stories of redemption abound among those who’ve come through Mountainview program, proponents say.

The program has recruited 70 students since its inception in 2005, when its first and only student was admitted, and 45 students were matriculating as of the fall of 2012, according to program materials.

Six students have already graduated, and nine more are on track to graduate this spring. Among the six graduates, three graduated with distinction and one with a perfect 4.0.

“To the best of my knowledge, the six guys who graduated from the program all either have jobs or are in graduate school,” Roden said.

“As long as they’re plugged in — they’re in graduate schools or jobs of their own, I would be happy. They all tell me they wouldn’t be where they are without the Rutgers degree.”

The program has a way to go, said Roden, who is still assessing its effectiveness. Some indicators of program success include scholarship provision — Mountainview students have earned “countless merit scholarships over the past few years,” according to agency communications. Three students are Ronald E. McNair Scholars, and one recently became the first Rutgers student in 11 years to earn a Harry S. Truman?Scholarship.

Program retention rate is another metric for evaluation and 70.9 percent of program participants — compared with 78 percent for non-program students at Rutgers’ Newark campus and 90 percent at its New Brunswick campus — stay in the program.

Perhaps the most telling statistic is the recidivism rate among program participants compared to New Jersey inmates overall.

“There have been setbacks in the form of largely technical parole or halfway house violations, but our overall recidivism rate is an extremely low: 11.4 percent (versus an estimated 55 percent across the state),” according to Mountainview’s materials. “No Rutgers Mountainview student has had any negative encounters with either campus or New Brunswick city police since the inception of the program seven years ago.”

Recruitment takes confidence

A lot of thought goes into how inmates are recruited into the program. “We don’t let people get in the admissions pipeline unless we have a certain degree of confidence,” Roden said, referring to a candidate’s ability to get through college.

Roden said applicants are asked to visit campus three times as a way to gauge their level of interest. Missing any one of those appointments can be end of the applicant’s quest.

University administrators also conduct what Roden referred to as a “judicial review” to consider the applicant’s offense and other factors.

“Obviously there are some offenses that raise more eyebrows than others,” Roden said. “Many of our students have nonviolent drug offenses, which are of less concern.

“But we still review each case because we want the program to succeed, and we want the students to be fully committed.”

Not everyone gets in after the judicial review, Roden said, and some are discouraged from even applying until they prove themselves for another year on parole.

“There are various ways to ensure that the community, the overall Rutgers community, is protected,” Roden said. “I bear that responsibility.”

The review process also considers students’ academic experience. Those who haven’t taken the prerequisite math courses don’t get in.

“We’re taking the stronger students,” Roden said. “But I think that the potential is huge because once the word is spread it gives incentives for the guys in custody to take their courses more seriously.”

Higher education to lessen crime

Once admitted, Roden said, “The chance of recidivism goes way down,” whereas non-program participants often resort to crime, “so the cycle just continues.”

“So it’s a waste of taxpayers’ money. It’s much cheaper to have the students at Rutgers than to have the students at one of these facilities for the states,” Roden said.

Van Heydoorn, of the Prisoner Reentry Institute at CUNY, cited a plethora of research showing that higher education lowers recidivism rates.

The Obama administration, and more specifically, the U.S. Department of Education, recognizes what the research shows about the benefits of higher education for current or formerly incarcerated individuals.

In making the grant announcement, the U.S. Department of Education noted that each year 700,000 incarcerated individuals are released from federal and state prisons. “Yet, existing policies and programs too often fail to prepare released prisoners to reenter society, leading four of every 10 to commit new crimes or violate terms of their release within three years,” U.S. Department of Education materials state. “Failure to support successful rehabilitation costs states more than $50 billion annually.”

A new group of peers

The other thing that the program provides is a positive peer group that helps participants stay the course.

“One of the most important things that Mountainview did was it gave me an alternative. It surrounded me with individuals that believed in me, and that kind of helped push me,” said Ean Polke, 30, who is majoring in Africana studies with a minor in criminology. “As opposed to being surrounded by people who say ‘you’re not going to be anything,’ being in the Mountainview program helped give the drive to continue.”

Could former inmates get into Rutgers on their own by going through the front door?

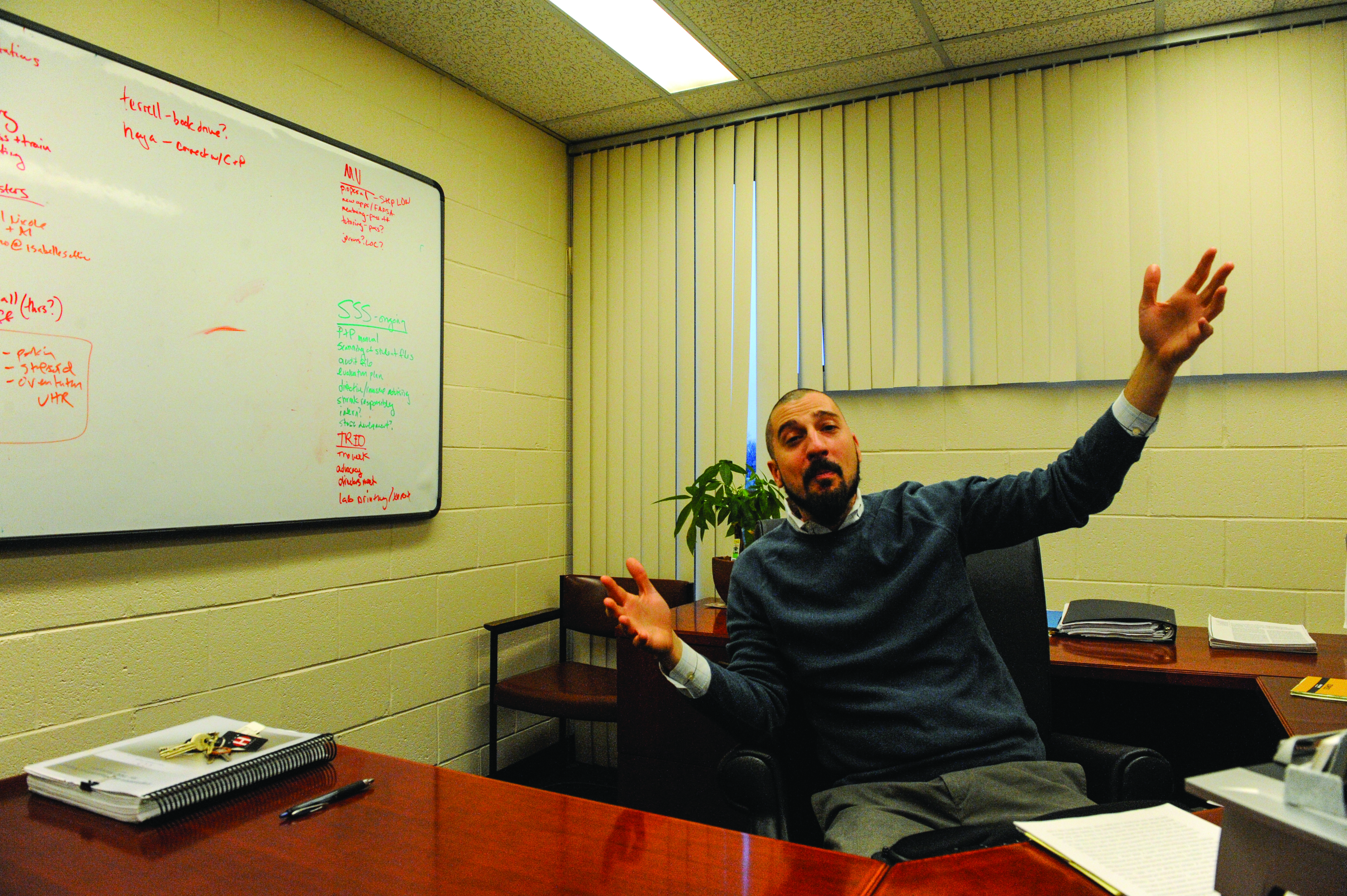

Mountainview program volunteer Christopher J. Agans, director of the Rutgers University?Student Support Services Program, said they could, but the program coordinators help participants by explaining certain peculiarities in their transcripts. For instance, a prospective student may have failed a course for no other reason than being moved from one correctional facility to another, thereby forcing the student to withdraw from the class and take an “F.”

Mountainview program volunteer Christopher J. Agans, director of the Rutgers University?Student Support Services Program, said they could, but the program coordinators help participants by explaining certain peculiarities in their transcripts. For instance, a prospective student may have failed a course for no other reason than being moved from one correctional facility to another, thereby forcing the student to withdraw from the class and take an “F.”

Also, program coordinators can help participants address prior convictions more effectively through their admissions essays. “While admissions doesn’t necessarily give us a clear [criteria] between what is admissible and what is not,” Agans said, “we can then put their best foot forward” so that admissions officials know more about the student than just how long they’ve been in prison and for what conviction.

Roden, of Rutgers, said Mountainview has some positive peers of its own. His program has aligned itself with Project Rebound, one of the older and most well-established such programs. It is part of the student government at San Francisco State University (SFSU), which was created in 1967 by Professor John Irwin as a way to matriculate ex-offenders directly from prison. Roden hopes to follow Project Rebound’s lead by eventually making it entirely student-run.

At the Prisoner Reentry Institute, where Van Heydoorn is director, researchers have created the Prison to College Pipeline, or P2CP. This initiative betweeen CUNY and the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision has the goal of increasing the number of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people who enroll in and graduate from college.

Jamaal Abdul-Alim is a Washington D.C.-based freelance writer. His work has appeared in The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel.