BALTIMORE — When Katrice Wiley, a longtime Baltimore City Public Schools administrator, served as principal at a 6-12 school on the city’s east side, she often grew frustrated when graduates would return and tell her they didn’t have enough money to complete college.

“I continued to graduate classes — the class of 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 — and I continued to see kids coming back,” Wiley recalled of her time at Friendship Academy of Engineering & Technology, recounting how some students even asked her for jobs as hall monitors so they could earn money to stay in school.

Wiley is confident those kind of situations won’t happen to students at a new health care specialty school she oversees at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School.

That’s because this school — actually a “school within a school” called P-TECH at Dunbar — is one of two new 9-14 schools in Baltimore that offer students the opportunity to graduate within six years or less with an associate degree — at no cost — in addition to their high school diplomas.

The other P-TECH school in Baltimore is located at Carver Vocational-Technical High School on the city’s west side.

Both schools — established last fall with $300,000 at the behest of Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan (R) in response to the Baltimore riots of 2015 — began with 50 students each and plan to enroll 50 students in each successive year until the schools reach full capacity their sixth year.

Baltimore’s P-TECH schools, as well as 10 others that Gov. Hogan hopes to establish in Maryland, are among the growing number of such schools throughout the nation patterned after the original P-TECH — an IBM-inspired school that started in Brooklyn in 2011. P-TECH stands for Pathways in Technology Early College High School.

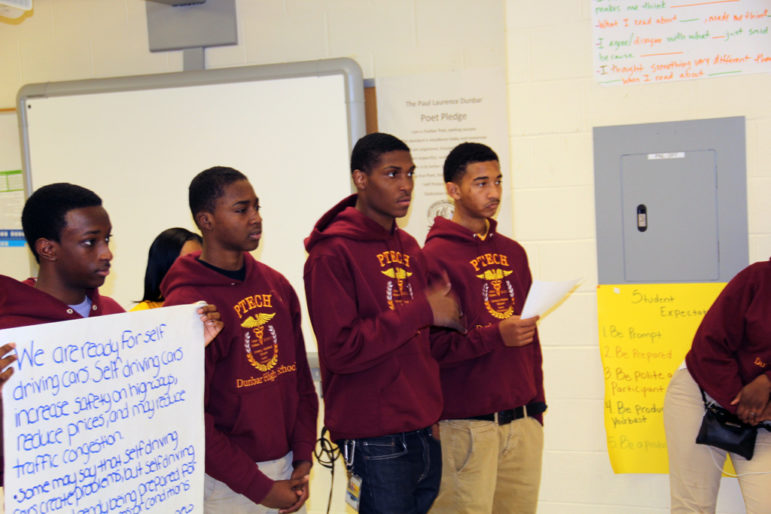

Several freshmen at P-TECH at Dunbar High School engage in a class debate about whether society is ready for self-driving cars. At the far right is Imonte Anderson, 15, who says he appreciates that the program provides mentors from the field he plans to enter and looks forward to taking college courses at Baltimore City Community College this summer.

A three-pronged model

“Each P-TECH school works with a corporate partner and a local community college to ensure an up-to-date curriculum that is academically rigorous and economically relevant,” states a written agreement between Baltimore City Public Schools and the Maryland State Department of Education.

There is no national oversight; the model is applied, funded and administered at the local level.

“Hallmarks of the program include one-on-one mentoring, workplace visits and skills instruction, paid summer internships and first-in-line consideration for job openings with a school’s partnering company,” the agreement states.

The prospect of gainful employment is what appeals to students such as Imonte Anderson, 15, who plans to pursue a career in physical therapy and considers himself “lucky” to be among the first 50 students at P-TECH at Dunbar.

Imonte says he appreciates the fact that the program provides mentors from the field he plans to enter. He also looks forward to taking college courses at Baltimore City Community College this summer.

“P-TECH, it creates a lot of options and a lot of things that can help us in our career, whatever we choose,” Anderson said. “We have pathways to help us so that we make lots of money when we graduate.

“Taking college courses, that helps us so that we finish college early, and when we graduate we’ll be able to get jobs that pay you $50,000 a year.”

In 2015, physical therapists earned a median salary of $84,020 per year, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Outlook Handbook. The handbook says the occupation is supposed to grow by 34 percent — “much faster than average” — through 2024.

Nicole Howard (right) and her daughter, Kyona, a freshman at P-TECH at Dunbar who aspires to become a veterinarian. Nicole Howard says she already refers other parents to look into P-TECH: “I tell them that it’s an amazing opportunity if they’re looking for a program where your kids can get a free education for a college degree.”

A model in progress

This June will represent a crucial milestone for the P-TECH model as students from the original cohort at P-TECH in Brooklyn complete the six-year program.

“It will be very interesting to see what those numbers are and to see kind of what happens to that class,” said Karen Elzey, vice president at the Business Higher Education Forum, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that works, among other things, to form strategic partnerships between higher education and the workforce.

Preliminary numbers from IBM show that to date, 54 students have graduated early from P-TECH Brooklyn — that is, with an associate’s degree in computer systems technology or electromechanical engineering — and are now pursuing their bachelor’s degrees full-time or starting their careers at IBM. Of those 54, an estimated 25 are pursuing their bachelor’s degrees full- time, and roughly 15 are in the process of applying to four-year universities.

Of the 100 or so students in the first cohort, 36 — more than one-third — are among those 54 early graduates, That means 36 percent of the class of 2011 has already received their diplomas, and that figure will grow in June.

Grace Suh, director of education programs at IBM, said those stats are noteworthy in light of how the on-time graduation rate nationally for two-year college students is less than 12 percent — a figure consistent with data from the National Student Clearinghouse.

“And when you look at STEM degrees, it’s in the single digits. For African-American young men earning two-year STEM degrees, the graduation rate is even lower,” Suh said.

According to a 2016 National Academy of Sciences publication titled “Barriers and Opportunities for 2-Year and 4-Year STEM Degrees: Systemic Change to Support Students’ Diverse Pathways,” it is “uncommon” for students to graduate on time.

The publication places the on-time completion rate for two-year associate’s degrees at 5 percent. It states that African- Americans complete two- and four-year STEM degrees at a rate of 9 percent, but that is within a period of four years. The rate rises to 22 percent at six years.

More than 70 percent of the 573 students at P-TECH Brooklyn qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Ninety-six percent are black or Hispanic, and 74 percent are male.

“For us to have this graduation rate at this time is very significant,” Suh said.

These freshmen are part of TECH at Dunbar’s first 50-student cohort. The school will add 50 students each year for six years, providing teens from low-income families a chance to earn an associate’s degree and prepare to work for with a corporate partner. Below: Simone Wade, 15, a freshman who leans toward becoming a registered nurse and ultimately aspires to become an obstetrician, says she was excited to get accepted at P-TECH and considers it a “great opportunity.”

P-TECH in Brooklyn posts results

Suh said P-TECH Brooklyn’s graduation rates should be even higher come June but that it would be premature to share the projected figures because they are not official.

In terms of job placement, Suh said eight P-TECH Brooklyn students have secured jobs at IBM, and two more were in the process of being hired at the time this article was being written.

For Wiley, the coordinator of P-TECH at Dunbar in Baltimore, those job placement figures — before the first cohort finishes its six years — are proof of P-TECH’s effectiveness. P-TECH at Dunbar has demographics that are similar to those at P-TECH in Brooklyn.

“To me, it’s proven itself,” Wiley said of P-TECH Brooklyn, praising the school for getting 10 students employed before the first cohort finished its six-year term.

Wiley predicted similar success at P-TECH at Dunbar.

“They probably won’t come back and say they need money to finish college,” Wiley said of future P-TECH at Dunbar graduates. “They won’t have to do that because they’ll have a job.”

Graduates of P-TECH at Dunbar will have the opportunity to get top consideration for jobs with the school’s postsecondary and industry partners: Johns Hopkins University, Johns Hopkins Hospital, health care giant Kaiser Permanente, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore

The school offers three health care career pathways: surgical technology, health care information technology and respiratory care.

“I think I’ll see, ‘Ms. Wiley, I’m now a surgical tech.’ ‘Ms. Wiley, I’m getting ready to go to med school, but I’m working as a respiratory care therapist until then,’” Wiley said. “So it’s gonna be a rewarding experience.”

Experts probe job prospects

Even if the two new P-TECH schools in Baltimore and others throughout the nation post positive job placement figures in the coming years, deeper questions — as with the P-TECH school in Brooklyn — remain behind the numbers.

Elzey, of the Business Higher Education Forum, says to truly assess P-TECH’s impact, it would be beneficial to track graduates longitudinally for years after graduation to determine if their P-TECH experience makes a meaningful difference in terms of their salaries.

While Suh, the IBM executive, says there is no such longitudinal study underway, Elzey has no shortage of questions she would like to see answered about P-TECH graduates.

“I think if you look at that cohort, I’d be interested in knowing what kind of jobs they’re getting. What is the breadth of those jobs?” Elzey said. “Are they only getting a certain type of job or are they finding that they’re qualified for a variety of jobs? What types of employers are hiring them?

“Are they filling jobs that are core competencies to the company and core responsibilities, and are the students getting jobs in a way that they’re not underemployed?”

Amy Loyd, associate vice president of the Building Educational Pathways for Youth program at Jobs for the Future, a national nonprofit that works to build educational and economic opportunity for underserved populations, said it’s important for initiatives such as P-TECH to provide broad education that is not only specific to the needs of an industry partner.

At JFF, Loyd helps oversee a P-TECH- inspired initiative in which SAP SE, a German multinational software corporation, is partnering with high schools and colleges in Queens, New York; Oakland, California; Boston, Massachusetts; and Vancouver, Canada.

“Whether it’s P-TECH or other nine through 14 models that we’re creating, we don’t want to create pathways for students to learn how to make a particular widget for a particular company that is not ultimately a transferrable skill that is stackable, portable,” Loyd said.

Rather, Loyd said it’s important for students to gain education that allows them to “broker their skills in the marketplace.”

“We’re really looking at building foundational skills as key,” Loyd said. “You can call them 21st-century skills, social emotional skills, noncognitive skills, they go by a lot of names.

“But essentially what are those employability skills that all employers need? And we find talking to employers across the country, employers often realize the old adage that they hire for hard skills, they fire for soft skills,” Loyd said.

Loyd added, “When you build out these pathways, you don’t want to build a pathway that leads to a credential that doesn’t have a readily attainable next step.”

Suh, of IBM, says the company is not prescriptive when it comes to the P-TECH curriculum and is not narrowly focused on training the students to be IBM employees.

“We’re not going in and training students on IBM WebSphere,” Suh said, referring to one of IBM’s signature software products. “What we are doing is saying this is the general set of skills that we require — both technical and soft — and working with our educators to determine how to help students attain those skills.”

Suh said P-TECH and P-TECH-inspired models are attractive to business because P-TECH “really lies at the nexus of education and workforce development.”

She points to the 300 or so businesses that have become partners with 62 P-TECH schools throughout the nation and the world. There are seven P-TECH schools in Australia and plans to open one soon in Morocco.

“So, if businesses are wanting to address their own skills needs, then P-TECH provides them with a talent pipeline to begin to develop a workforce with the kind of skills that they’re going to need,” Suh said.

P-TECH is attractive to companies because it represents a way to be a good corporate citizen, she said. P-TECH also enables business to reach “a lot of untapped talent in different places across the country.” “It’s not checkbook philanthropy,” Suh continued. “We’re really investing in sweat equity.”

Among other things, Suh said P-TECH provides skills mapping, mentors for students, worksite visits, project days, “hackathons” and guest lecturers.

When students are deemed ready, she said, they get skills-based paid internships, “so they have an opportunity to take what they learned at school and apply it to an actual work setting working on a real project for IBM or another industry partner.”

“And then ultimately at the end of the day, they are first in line for jobs,” Suh said. “And that’s not a promise of a job but it means they’ll get an interview.”

Jamaal Abdul-Alim is a 2017 Education Writers Association Reporting Fellow who is examining the effectiveness of P-TECH and other dual-enrollment programs that enable students to earn both a high school diploma and an associate’s degree in a high-growth field. He is a senior staff writer at Diverse: Issues in Higher Education and resides in Washington, D.C.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS, GO TO THE OST HUB.