How organizational practices enabled molesters, until victims forced changes

One morning in 1969, a boy nearly ignited a sex abuse scandal in Wilmington, Del., by showing up late for school.

“This has gotta stop,” the middle school’s assistant principal, Robert Cline, said as he walked the boy to his office. The boy explained that he’d overslept again because he had stayed late at a teacher’s apartment. That set off a string of questions from Cline for which each answer got worse: Mr. Bittenbender helps us with homework. Yes, other boys go to his apartment. Well, he also gives us massages. Yes, the massages go down there.

Cline summoned more boys; they told the same story. Then came Carlton Bittenbender. He said he was just trying to befriend some neglected kids. Then he signed a resignation letter.

On his way out of town, Bittenbender dropped by an Episcopal church that sponsored the Boy Scout troop for which Bittenbender was Scoutmaster. He told the pastor about the trouble at school and that he’d done the same thing with a couple of Scouts. The pastor told the troop leaders, who confirmed the story with the boys.

No one talked to other students or scouts to see if they’d been molested; no one called police, and no one informed Boy Scout headquarters. Bittenbender went on to teach in Connecticut and to lead Scout troops in Rhode Island and Virginia. At each of those last two stops, he was later convicted of molesting Scouts.

While that chain of events might seem shocking today, those school, church and troop leaders acted in the typical fashion of the time. As for today, although the Penn State and Catholic Church sex-abuse scandals compel people to demand, “How could this happen?”, what happened in those institutions is not so unusual.

When you get beyond castigating one organization or another about sex abuse and look instead across institutions that work with young people, you find similar patterns of behavior among those who mishandled the problem. The basic details of institutional sex-abuse scandal are really no surprise; all across the youth field – from school, church and camp to sports, foster care and juvenile detention – people dedicated to helping children sometimes fall into a common sequence of reactions when confronted with sex abuse, inadvertently achieving the opposite of their mission: They enable child molesters at the expense of kids.

When you get beyond castigating one organization or another about sex abuse and look instead across institutions that work with young people, you find similar patterns of behavior among those who mishandled the problem. The basic details of institutional sex-abuse scandal are really no surprise; all across the youth field – from school, church and camp to sports, foster care and juvenile detention – people dedicated to helping children sometimes fall into a common sequence of reactions when confronted with sex abuse, inadvertently achieving the opposite of their mission: They enable child molesters at the expense of kids.

Those behavior patterns show up repeatedly amid thousands of abuse cases from youth-serving organizations during the past several decades. They include putting too much faith in adult colleagues while dismissing victims, minimizing the extent of abuse within the institution, failing to educate staff about abuse, and hiding abuse from the public, parents and police.

This dismissive behavior happens despite the fact that “these are not evil people,” says Kelly Clark, an Oregon attorney who has successfully sued numerous youth groups over sex abuse. “Nobody ever woke up and said ‘How we can create a culture of child abuse here?’”

Rather, the culture of enabling grew from an instinct to protect the organization first. “They all didn’t care, or the higher ups didn’t think it was important enough” to confront the problem, says Matt Stewart, a California man who was abused by his Scoutmaster in the 1980s.

Stewart, who settled a lawsuit against the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) in 2007, sees abuse scandals engulfing other institutions as well and says, “They all didn’t do enough to help kids.”

Caveats are crucial here: This enabling behavior was not standard operating procedure, as evidenced by the fact that most youth-serving organizations remain unscathed by big damage awards and involving abuse. Even organizations accused of bumbling abuse incidents can point to cases where administrators and field workers responded quickly and followed proper procedures. And youth-serving organizations have made enormous strides in recent years to improve abuse prevention and reporting.

Still, people in the field are a bit nervous. The recent multi-million dollar punishments from juries and governing bodies, the criminal charges against the likes of bishops and school superintendents, and the public erosion of institutional trust have driven organizations to redouble their efforts to prevent abuse and investigate claims. “People are seeing what happens when you don’t deal with it with great rigor,” said David Shapiro, CEO of MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership.

The youth field should learn from the scandals, said Charles Pierson, CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters of America (BBBSA): “I hope the situation with Jerry Sandusky [convicted of child molestation at Penn State University] raises awareness at the highest levels across the country that the work is inherently risky business, and you have to be partnering with serious organizations committed to world-class safety.”

Following are some lessons gleaned from criminal and civil cases, government investigations, and newspaper reports about organizations accused of mishandling incidents of abuse.

Adults favored; kids dismissed

In February 2008, a teen at the LeFlore County Juvenile Detention Center in Greenwood, Miss., reported that he was sexually assaulted by a staff member. The boy then attempted suicide. Detention center managers interviewed the boy and the staffer, and concluded that the youth was lying “to gain sympathy.” In a letter to the local police chief, the center’s director wrote, “Do not let this troubled young man’s false allegations stop [the county] from allowing Leflore County to serving [sic] your Juvenile Detainment Needs.”

“Egregiously deficient” is how the U.S. Department of Justice described that investigation in a report about LeFlore last year. That probe found “systematic” abuse of youth, including “repeated harm by failing to properly report and investigate abuse by staff.”

A fundamental problem at LeFlore was an organizational culture that worked against youth who made claims against adults — a common element of institutional abuse scandals. In such cases, the administrators who hear the accusations often know the adult, might have risen up through the ranks with him, and consider him a reliable or even exemplary employee. As for the kids: The administrators often know little about them or perhaps they’ve caused trouble before.

This phenomenon is especially blatant in detention facilities, where youths arrive with less credibility than, say, a Boy Scout. “You deal with false accusations every day,” explained Caleb Asbridge, senior associate for juvenile services at the Moss Group, a Washington-based consultant firm that works under federal contracts to improve procedures at juvenile justice facilities. The accusations run from trivial (“this person didn’t let me have dessert”) to severe (“this person beat me up”), and although some are true, Asbridge noted that eventually “you get a callused effect on your response mechanism.”

Other factors that fuel abuse in detention, Asbridge said: poor staff training on how to interact with kids, fear of retribution for reporting abuse by a colleague, and difficulty in finding qualified staff, leaving administrators desperate to keep their workers.

Familiarity between authorities and offenders can work against victims in any institution. Orthodox Jewish organizations in New York and New Jersey have been hit with numerous lawsuits, criminal charges and scathing news reports in recent years for allegedly dismissing and suppressing allegations against rabbis, teachers and camp staff. One lawsuit against a Jewish day school in Brooklyn claims that the rabbis who looked into the accusations against their colleague told the victims that “they were not actually abused” – an assurance that failed to stand up when the man was later convicted by secular authorities.

Secular authorities can be equally skeptical of accusers. In public schools, the practice of dismissing student accusations has been so rampant that the largest federal study of abuse in public schools, published by the U.S. Department of Education in 2004, noted that “the most common reason that students don’t report educator sexual misconduct is fear that they won’t be believed.”

That fear extends to sports as well. In 2010, Deena Deardurff Schmidt, a 1972 Olympic champion swimmer, revealed that she had been repeatedly molested by her coach in the 1960s. In a recent deposition for a lawsuit by another swimmer, Schmidt said that when she reported the abuse, no one investigated: “Most everyone I told in coaching gave me an answer that I felt was very vague and dismissive, that my coach was a great coach.”

The result of such dismissiveness, wrote Charol Shakeshaft, author of the federal study of public schools: “Abuse is allowed to continue.”

Faith skewed their vision

Many youth-serving organizations are blessed to be staffed by people with an almost religious faith in the organization’s work. As well-founded as that faith might be, it can also be blinding.

Micky McAllister found that out when the BSA drafted him in the 1980s to help institute stronger abuse-prevention efforts. McAllister, a longtime professional Scouter, found that Scout leaders around the country saw little reason to discuss sex abuse with Scouts and their parents. “Here we are, an organization chartered by Congress for the best program of Americanism and country and God, and we did not feel originally that this could infiltrate our organization,” McAllister said.

Scouting is the core youth program for boys in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), which has faced on onslaught of lawsuits for going easy on both Scout leaders and church staffers who allegedly abuse children. In discussing an offender within the Mormon Church who was continually allowed access to children despite having been accused before, one woman told the Phoenix New Times that her fellow Mormons have a hard time believing that such things can happen among them.

“I think there are a lot of us who like to think that we live in a perfect world, and it’s really painful and difficult to realize that we don’t,” said Chris Rampton-Lowe, a victim of sexual abuse. “It’s just much easier to stay in denial about such things.”

Organizations nourish such denial by keeping mum about abuse incidents, even among their own people. While youth groups have long produced materials for staff and volunteers that discuss sex abuse, they can almost never bring themselves to flat-out state that they’ve experienced the problem themselves. More often than not, an incident of abuse in a church, school, or summer camp was the only case that the staff ever heard of. To them it was an aberration; they had no idea if it was part of a systemic problem.

Would the pastor and troop leaders in Delaware have reacted differently to Bittenbender’s quiet escape in 1969 if they’d known that during the previous three years, 217 people had been banned from Scouting for the same offense?

While some national youth-serving organizations (such as the BSA, BBBSA and the Salvation Army) say they maintain systems to track people who’ve been banned for inappropriate conduct with youth, almost none say they count the cases or study them for patterns. (USA Swimming and USA Gymnastics, which are governing bodies for their sports, post lists of banned people on their websites, and thus the cases can be counted.)

BBBSA began examining abuse cases in the 1980s to look for trends, and Julie Novak, associate vice president for child safety, says she looks at individual cases to inform the organization’s procedures for preventing abuse and responding to allegations. She says the organization has no total figure.

In 1995, a group of researchers at Brigham Young University and Arizona State University presented the LDS with a study of 71 women who had reported to church hierarchy that they had been sexually abused as children. Forty-nine of those women reported “negative interactions” with the bishops in whom they had confided, saying the bishops had been “judgmental,” “unbelieving” and “protective of the perpetrators.” The church rejected the study as flawed. It was later published in Affilia: The Journal of Women and Social Work.

“It’s like it was bad news they didn’t want to hear,” one of the researchers, Karen E. Gerdes, told the Houston Chronicle. “I was excited because I thought the church was going to be pleased to get this information so they could put it to good use.”

Keeping mum about abuse incidents infuriates Stewart, the victim from California. He said that if the BSA had told troop leaders and parents about common behaviors among molesters in Scouting, a lot of kids would not have been abused. His molester routinely took one or two kids on special camping trips — a tactic that runs throughout the BSA’s files on molesters. “If you would have told my mother” that that was a red flag, Stewart said, she would have not have let him go.

They didn’t know what to do

Working on a sex abuse case is painful. Julie Novak knows. The BBBSA executive recalls that more than 10 years ago, when she was CEO of a Big Brothers Big Sisters affiliate, a big brother was accused of molesting someone outside the organization. Novak asked investigators to look into whether the offender had done the same with his little brother. (He had not.)

“I came home every night from work and cried,” Novak recalled. “I’m not a crier.”

Novak had been trained on how to handle suspicions of abuse. Administrators and frontline workers who have been accused of mishandling abuse cases often report that they’d received little or no education about how molesters typically operate or how to respond to allegations. National organizations might have had written procedures somewhere, but the procedures were often not well-known or not well-enforced. Before the wave of sex abuse lawsuits picked up in the mid 1980s, most youth-serving organizations had little to say about the problem.

Consider the school, church, and troop leaders who were confronted with Bittenbender’s confession in 1969: Unaware about the extent of abuse in youth groups or the molester’s penchant for repeating offenses in one place after another, they were relieved to see Bittenbender walk away with a promise to never molest again.

Such promises have gotten many an offender off the hook, especially when buttressed by commitments to get counseling. A key element in the Catholic Church scandal was the practice of shuttling abusive priests to therapy, then returning them to parishes, supposedly cured. Asbridge of the Moss Group suggested that those who work with troubled young people are particularly vulnerable to pledges to straighten up: “We believe in redeemability.”

Administrators also sometimes believe too much in their ability to resolve problems on their own, Asbridge said. They think, “I’m going to call this person in and read him the riot act. I’m yelling and screaming and telling him he’s got to stop. That’s going to get it fixed.”

That thinking produced disastrous consequences for countless children who were later molested by freed offenders. Those offenders include:

- Emanuel Yegutkin, a camp counselor and principal at a private Jewish school in Brooklyn, who quietly went through treatment by the order of rabbis instead of being prosecuted, only to be charged years later with 110 counts of abusing two boys;

- Thomas Hacker, who was kicked out of a Illinois Boy Scout troop with all charges dropped as long as he got counseling. (“Didn’t take the treatment seriously,” he later wrote.) He joined another troop, became recreation director in a Chicago suburb, got arrested for child molesting, and eventually confessed to molesting hundreds of boys; and

- Untold numbers of the 225 New York educators who, according to a 1994 study by Charol Shakeshaft and Audrey Cohan, admitted molesting students, but “none of the abusers was reported to authorities. … Nearly 39 percent chose to leave the district, most with positive recommendations or even retirement packages intact. …

“Superintendents reported that 16 percent were teaching in other schools and that they had no idea what the other 84 percent were doing.”

Why they kept quiet

In the Orthodox Jewish community of Lakewood, N.J., a family told their local rabbinical tribunal about three years ago that their son had been molested by a man who served as yeshiva teacher and camp counselor. When that council dragged its feet, the family reported the incidents to legal authorities and the man was arrested – setting off a campaign by some community leaders to stop anyone from cooperating with prosecutors. Several rabbis distributed a proclamation saying that accusers “may not bring any accusations to the secular authorities.” One rabbi allegedly urged other residents to pressure the family to drop the criminal case; rabbinical leaders denied such pressure.

They did say they prefer to handle abuse cases internally. Rabbi Matisyahu Salomon, a teacher at Lakewood yeshiva, told the Asbury Park Press in 2009, “Perpetrators and predators must be punished, albeit not in the limelight.”

Avoiding the limelight can dominate the institutional response. Leaders who don’t know what to do about molesters do know that public exposure can do incredible harm to their institution’s image.

Clark, the plaintiff’s attorney from Oregon, characterized the thinking this way: “We’ve got to protect our reputation here. Our work is so important, we can’t let it be compromised by these little unfortunate things that happened.”

That’s what drove the cover-up of abuse at Penn State, according to the report by the task force that the university hired to investigate the case: “In order to avoid the consequences of bad publicity, the most powerful leaders at the University … repeatedly concealed critical facts relating to Sandusky’s child abuse from the authorities, the university’s Board of Trustees, the Penn State community, and the public at large. The avoidance of the consequences of bad publicity is the most significant, but not the only, cause for this failure to protect child victims and report to authorities.”

A hushing culture also permeated much of Scouting for decades. In 1978, a Scout executive in Massachusetts wrote to national headquarters that one of his volunteers admitted “that he engaged in sexual acts with one of our Scouts.” The volunteer resigned, and the parents “fortunately have decided not to press charges.” The Scout executive later explained, “I preferred not to have that kind of publicity.”

Youth sports have long favored silence as well. A Seattle Times project in 2004 looked at the cases of 159 school-based coaches in Washington who were reprimanded or fired for sexual misconduct, and found that school districts “routinely keep investigations secret by failing to document them or by signing agreements with accused coaches promising not to tell” as long as they resigned.

Asbridge of the Moss Group — who has seen the keep-it-quiet culture in juvenile detention facilities — offered this advice to administrators: “If you don’t have a reporting culture and you don’t have a strong investigative piece where people are confident that investigations are thorough and impartial and that the truth is going to come out, you’re still going to have a problem with sexual abuse.”

Victims force changes

The reasons behind a suicide are typically complex, but when 12-year-old Christopher Schultz killed himself in 1979 by swallowing oil of wintergreen, his family knew that one factor was the abuse that Christopher had suffered at the hands of a Franciscan brother who had been his Catholic school teacher and Scoutmaster. The family sued the Newark Archdiocese, only to find that the state’s charitable immunity law absolved churches of liability for employee negligence. When they sued the BSA in New York, the court ruled that the case belonged in New Jersey.

How things have changed

For years, families who leveled accusations about sex abuse by leaders in nonprofit organizations had little voice. The difficulty of winning abuse convictions made prosecutors hesitant to proceed, state laws limited civil options against charities, and judges and juries went easy on nonprofits for what they thought were rare events.

The mood began shifting significantly in the mid-1980s. Lawsuits against organizations like the Church, schools and the BSA mounted, media coverage exploded, and damage awards grew — a cycle that fed itself as the abuse revelations empowered victims to talk and eroded sympathy for the institutions. Some say the pendulum has swung too far, as charities have been hit with huge damage awards for actions that took place decades ago, when they reacted in ways that were typical of the time. Abuse experts and youth organization leaders say that regardless of what one thinks about the punishment that’s been meted out, the lawsuits and the publicity have advanced children’s protection by:

- De-stigmatizing abuse, making it easier for children to report the crime;

- Making institutional sex abuse a national issue and expanding public knowledge about the extent of the problem. David Finkelhor, director of the University of New Hampshire’s Crimes against Children Research Center, wrote in Child Abuse & Neglect that lawsuits against the Catholic Church forced “disclosures that allowed the scope of the problem to be appreciated fully.”

- Compelling organizations to improve how they prevent abuse and handle allegations. Finkelhor sees “a more alert and vigilant organizational environment.” Sarah Kremer, who leads mentor screening and youth safety training as program director for Friends for Youth’s Mentoring Institute, said, “More programs are putting into place really strong prevention steps” and procedures to handle accusations.

- Driving the passage of new laws that require more people who work with youth to report suspected abuse to authorities. “It’s finally connecting with the general public,” said Kremer, whose institute is part of Friends for Youth in Redwood City, Calif. “It seems like people are not just only outraged, but they’re asking for changes, too.”

The connection between legal action and actual change is most clear in juvenile corrections. The U.S. Department of Justice has filed lawsuits against several state systems over abuse allegations, and has mandated overhauls in those systems to make it less likely that abuse will happen and more likely that it will be well-investigated. In March, the department issued rules to curtail abuse, including greater supervision of youth and banning contact between youth and adults in common areas.

The connection is also clear at USA Swimming, which in 2010 came under attack in a report by the ABC News program “20/20.” The report said the governing organization failed to act against numerous alleged molesters and had covered up an abuse problem in the sport. The organization says it looked at every case reported to it, but within two weeks of the news program announced the tightening of existing policies and the enactment of new ones, including posting online its list of people (mostly coaches) who’ve been banned for life for inappropriate behavior (mostly sex offenses). In the past two years another governing body, USA Gymnastics, launched investigations and instituted new abuse prevention and reporting rules in response to a wave of media reports about former gymnasts who say their coaches molested them.

Jurors have tried to force changes as well, although organizations say their upgrades to child protection procedures are unrelated to legal action. “Media and legal attention have nothing to do with our desire to prevent abuse,” the LDS Church told Youth Today. When a jury in Montgomery County, Texas, hit the LDS with a $4 million verdict in a sex abuse case in 1998, the jury foreman told the Houston Chronicle, “We wanted to go for a big number because we felt maybe they need to start thinking about this when they hear from people who go to them and tell them there’s abuse going on. You can’t just sweep this stuff under the rug and act like you don’t hear it.”

Similarly, a jury in Portland, Ore., sent a message in 2010 with a judgment of $1.5 million in actual damages against the BSA, then $18.5 million in punitive damages. Within months, the BSA (facing more lawsuits) announced that all of its volunteers must go through training about sex abuse, after years of saying that it could not require them to do so. (The plaintiff’s attorney, Clark, made that a main point of his argument for damages.)

Speaking of lawsuits: In 2006, New Jersey’s charitable immunity law was amended to exclude protection of nonprofit charities from lawsuits over alleged sex abuse. Those pushing for the change cited the Catholic Church scandal and the case of Christopher Schultz, the Scout who committed suicide.

In public schools, which have faced countless lawsuits and media exposés, change has been significant, albeit uneven in districts around the country. Perhaps nowhere is the new attitude more clear than in Los Angeles, where this summer Superintendent John Deasy fired the entire staff of an elementary school (including the janitors) that faces public allegations of having harbored for 23 years a teacher who routinely used sex games to molest children.

While such changes address the problem to varying degrees, nothing is foolproof. “Even with every step we can think of” to screen applicants, said Kremer of the Mentoring Institute, “there’s still the possibility of an inappropriate candidate getting into the program.”

That’s why youth-serving organizations keep revising their procedures. Leaders from many of those organizations will gather in Atlanta this fall for a conference on child protection, hosted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and the BSA.

“You can never be too safe,” said Pierson of the BBBSA. “The only way to completely be fool proof is not to do what we do at all. And that is not an option.”

Patrick Boyle is the former editor of Youth Today and the author of “Scouts’ Honor: Sexual Abuse in America’s Most Trusted Institution.”

Sexual abuse in the BSA

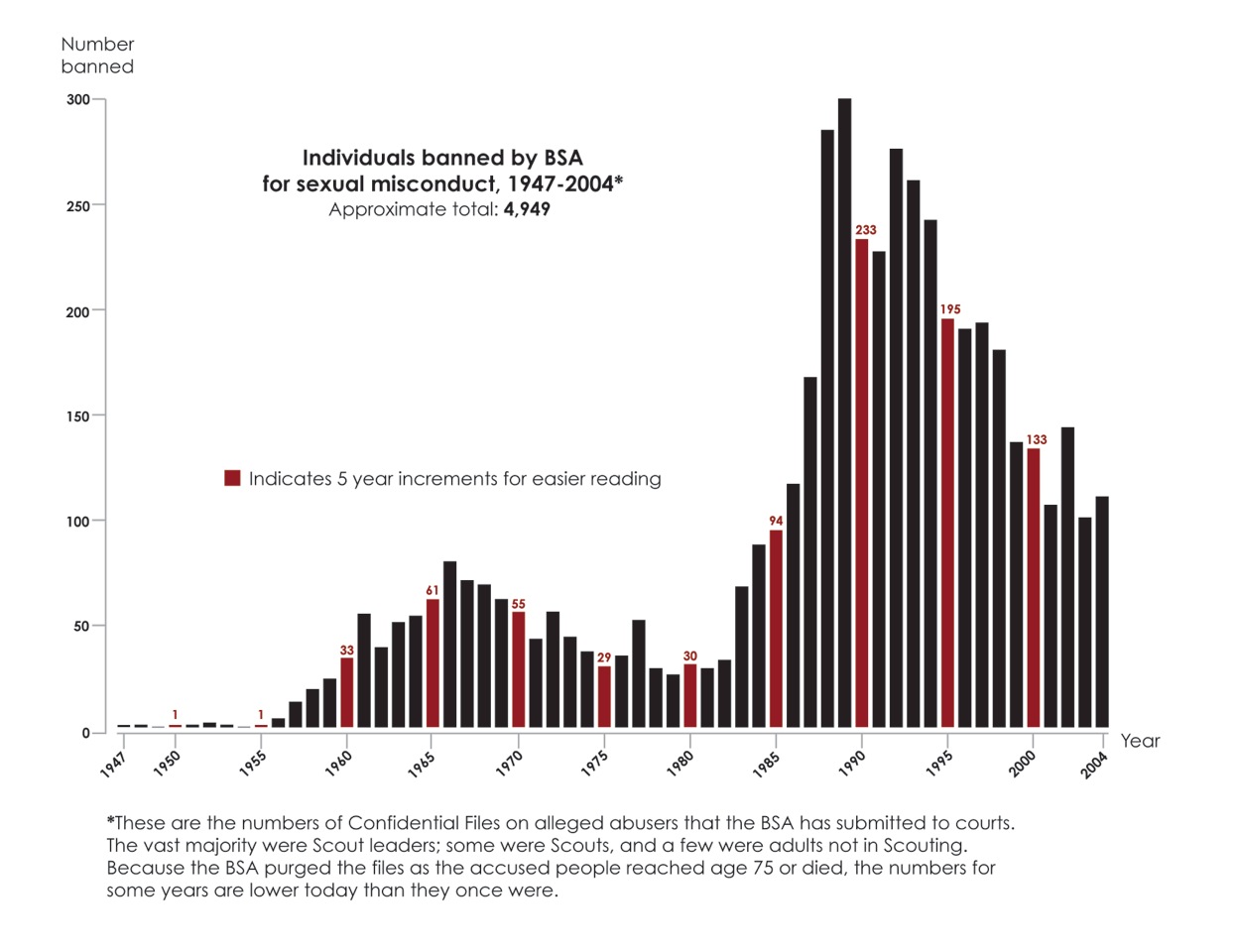

The Boy Scouts of America has long kept “Confidential Files” on people that it banned for various offenses, including sex abuse. The files on those banned for sex offenses – submitted as evidence in lawsuits under court order – show that the BSA banned about 5,000 people from 1947 through 2004.

The figures in the chart above come from two sets of files: 1,800 more submitted in a California lawsuit in the 1990s, covering 1971-91, and about 5,000 submitted in a Washington state lawsuit in the 2000s. The latter set of files was not made public, but the plaintiff’s attorney, Tim Kosnoff, compiled and made available an index of the files from 1947 through 2004.

The data show that the number of people banned for alleged misconduct with youth began rising significantly in the mid and late 1980s – at a time when national media coverage of sex abuse was growing, and as the BSA introduced new materials for its leaders and youths about recognizing and reporting sex abuse.

(See sidebar: “Protect the Child: a How-to Guide“)