Over the past two years, Patrick Welch has grown accustomed to prison life. The metro Atlanta native must wear a uniform every day. He frequently must step through metal detectors and be patted down by security officers who are checking for weapons and drugs. He can’t move about his living space freely. Common personal items – including cash – are considered “contraband” and therefore are banned. He eats, sleeps and socializes exclusively with the 500 men in his unit.

As an inmate at Coffee Correctional Facility in far southeastern Georgia, Welch, 20, said he was well-prepared for prison life after spending eight months at an Atlanta Public Schools alternative school for disruptive students. A civil rights attorney described the school, Forrest Hill Academy (FHA), as a “prison before prison for the kids.”

As an inmate at Coffee Correctional Facility in far southeastern Georgia, Welch, 20, said he was well-prepared for prison life after spending eight months at an Atlanta Public Schools alternative school for disruptive students. A civil rights attorney described the school, Forrest Hill Academy (FHA), as a “prison before prison for the kids.”

Officially, the school was designated as the educational home for hundreds of Atlanta youths moving in and out of the juvenile justice system and those teetering on the edge. In 2008, the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia sued the school system for operating the middle and high schools as what the group said was actually a “warehouse for poor children of color.”

The increased imposition of zero tolerance policies across the country has spawned similar alternative schools, used to separate suspended students and others with behavioral problems from regular classrooms.

Before he was arrested in 2009, convicted of robbery, hijacking a vehicle, gang participation and theft by taking and sentenced to six years in prison under Georgia’s First Offender Act, Welch was one of the eight named plaintiffs in the 2008 lawsuit seeking improvements at the school.

Welch’s mother, Patti Welch, said in an interview that conditions at FHA turned her son off from school.

“Patrick never had any homework; it was ridiculous,” she recalled. “He started skipping school a lot because he told me he got tired of sitting in a room all day with no teaching, no learning, no motivation – nothing.”

Prison Before Prison

The ACLU lawsuit against the school system and the private company that operated Forrest Hill, Community Education Partners Inc. (CEP), cited a litany of problems at the school: no gym, no library, no common cafeteria, security worthy of a prison and, sometimes, physical restraint of students.

The for-profit CEP was paid about $7 million a year from 2002 to 2009 to oversee the education of FHA’s nearly 450 students.

The for-profit CEP was paid about $7 million a year from 2002 to 2009 to oversee the education of FHA’s nearly 450 students.

“Our clients felt and expressed to us that they were not receiving the constitutionally adequate education to which they were guaranteed by the Georgia Constitution,” said Chara Fisher Jackson, legal director of the Georgia ACLU. “The privatization aspect has lots of concerns for us, to have a private entity be the primary responsible party for what has been determined to be a state obligation.”

The ACLU asserted that CEP’s failure to help students academically or behaviorally, or to provide them with meaningful opportunities to return to a traditional school, contributed to its reputation as merely a “dumping ground for unwanted students.” The school’s motto, “Be Here, Behave, Be Learning,” reflected CEP’s priorities, the suit claimed.

Each morning, students were separated by sex and walked through metal detectors. Some students, the suit alleged, said security officers of the opposite sex sometimes subjected them to invasive body searches. “It seemed almost Draconian,” said Atlanta-based civil rights attorney Gerald Griggs, after reviewing the ACLU’s allegations.

Students were restricted from taking anything into or out of the building – even textbooks and notebooks, which were considered contraband. CEP officials said that all essential items – even feminine hygiene products for the girls – were provided on site. Once inside, students retreated to sex-segregated classes in isolated pods within the building known as “learning communities.” They remained there throughout the school day.

“They would make you take your shoes off and pat you down like the police pat you down,” Welch said. “It bothered me that we didn’t have a lot of freedom in there. It felt like you was in jail at that school.”

Fisher Jackson said Welch’s concerns were valid.

“All of the things that we know enhance the educational process – not just our opinion, but what has been empirically proven to enhance education and what kids really need to succeed – those things were not available at Forrest Hill Academy,” she said.

Standardized test scores showed that the student body – almost entirely African-American and poor – was failing miserably, with little to no meaningful intervention. Although the school enrolled grades six through 11, most students arrived with math and reading skills at a third-grade level. They didn’t do much better after their time at Forrest Hill (usually one to two semesters), state figures suggest. At one point, nine out of 10 students were unable to pass the state standardized test for math proficiency. Data from the 2006-07 school year show that 91 percent of the academy’s students failed the state’s assessment test in mathematics and 66 percent failed the reading portion.

Students from as many as three different grades were often combined in classes, all working on the same material, according to the lawsuit.

“They would give you little easy work, man,” recalled Welch. “They would give you a worksheet and let you look in the book for the answers. The teachers would just sit there all day. They would just hand you work, but don’t go over it with you.”

ACLU officials claimed some teachers and administrators hit students, threw books at them and slammed them against walls and f loors. School resource officers and police officers regularly restrained students in chokeholds, the suit alleged. FHA in general failed to provide adequate security for a safe environment.

Ultimately, the school system terminated CEP’s contract and resumed control of FHA. The school system agreed to adhere to a state-mandated curriculum similar to that of other Atlanta public schools and to provide special services for students with disabilities.

The lawsuit was settled in December 2009 and earlier this year the ACLU moved to end its monitoring of the school.

“This litigation was very important, beyond what happened at Forrest Hill, because it raised awareness about these issues, even in other school systems,” said Marlyn Tillman, a client liaison for the suit. “A lot of people said they didn’t know that these issues existed before this case. There’s a lot of misconception out there that these are the ‘bad kids;’ that they are the ‘throwaway kids.’ I don’t think you should throw any kids away.”

Fisher Jackson agreed, calling the FHA victory far-reaching.

“It’s now run by the Atlanta Independent School System; they no longer contract out to a private for-profit company to administer the education policies at the school,” she said. “And I think [APS] has taken significant steps to address our concerns and are monitoring those closely to make sure that student rights are respected and that students receive the quality education that they need.”

“It’s now run by the Atlanta Independent School System; they no longer contract out to a private for-profit company to administer the education policies at the school,” she said. “And I think [APS] has taken significant steps to address our concerns and are monitoring those closely to make sure that student rights are respected and that students receive the quality education that they need.”

A new beginning

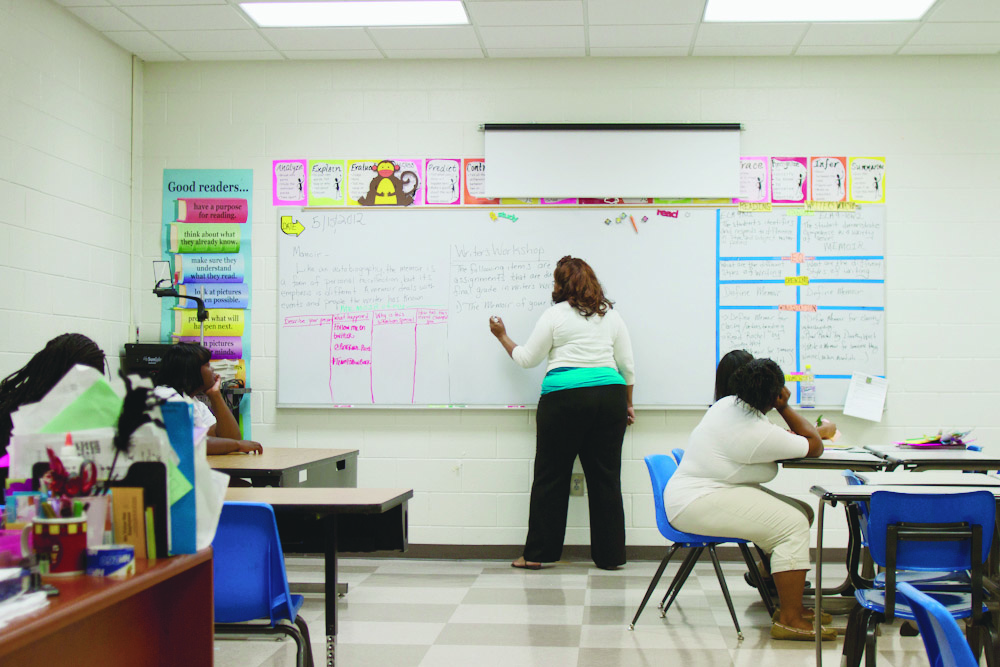

Tucked off a tree-lined road in Southwest Atlanta, the forest green color scheme sprinkled throughout the pristine tan brick building is the only reminder of the CEP days, Assistant Principal Kelli Swinson said during a recent tour. “This mural had the letters CEP painted on it, so we painted over it,” she said. “We didn’t want any trace of CEP left here.”

Swinson and Principal Robert Robbins pointed to other changes, including an entirely new faculty and administrators who came on board after APS regained control.

“I think there’s more order in this school, and at this school, there must be order,” insisted Robbins, a veteran APS principal who was appointed to the post for the 2011-12 school year.

The school, for example, still has no gym or common cafeteria; but students have access to a new library and career center. Each morning, they still undergo airport-style security measures, but now officers of the same sex as each student conduct the screenings. Students may bring in notebooks and writing utensils, Swinson said. Textbooks may be checked out, but are not routinely distributed to students.

Swinson said most classrooms have a teacher and a paraprofessional assistant paired together. The student/teacher ratio maxes out at 18:1 (compared with 32:1 in most traditional APS schools).

“A lot of the students come in with the old [school’s] mentality; they heard that this wasn’t a real school,” said middle school language arts teacher Ronnie Banyard Jr. “They’re so surprised when they’re met with such rigorous work. They say, ‘They told us we weren’t going to be doing [such challenging] work here.’”

Both ACLU and FHA officials confirm that the “dehumanizing” and “unconstitutional” body searches that were commonplace under CEP no longer happen. “Not under this watch,” said Swinson. “We haven’t had many problems with anyone trying to bring in weapons. Sometimes the girls try to sneak cell phones in under their shirts, which they know is against the rules. If [the metal detectors] start buzzing, we ask them to remove it themselves, or we call their parents.”

The isolated sex-segregated “communities” within the building remain. “It keeps the distractions down,” said Swinson, noting that some other APS schools also use the single-sex model. “Nobody’s trying to impress anyone of the opposite sex or prove anything. This helps students focus better on their work. ”

Low standardized test scores remain a challenge, however. This spring, FHA was listed among 78 underperforming “priority” schools under Georgia’s current adaptation of the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) policy (state education officials applied for waivers to make adjustments). The “priority” distinction qualifies the school for three years of state assistance to help bring up scores.

Both Swinson and Robbins said FHA grapples with the same issues most alternative schools nationwide face – a negative reputation, limited resources and little control over who makes up the student body and at what point in the semester students arrive.

“It’s like the first day of school every day for the teachers,” said Swinson, a hint of exasperation in her voice. “We just try to do the best that we can with the students we are given.”

Despite the ACLU’s move to end monitoring, several areas of disagreement remain: over access to counseling services, whether Individualized Education Plans are being prepared for each student, retaining special education students more than 45 days and the surge of low-performing students who are shifted to FHA just before standardized tests are to be administered systemwide.

Despite the ACLU’s move to end monitoring, several areas of disagreement remain: over access to counseling services, whether Individualized Education Plans are being prepared for each student, retaining special education students more than 45 days and the surge of low-performing students who are shifted to FHA just before standardized tests are to be administered systemwide.

There are also continuing problems concerning the placement of special education students. Some critics insist they should be separated from others at FHA and provided more services.

Swinson said the school follows an “immersion” model, which keeps special education students in traditional classroom settings. The smaller class sizes allow the teacher and paraprofessional to help more students individually, she said.

Swinson and Robbins said they will submit a proposal soon to the APS Board of Education requesting, among other changes, that middle and high school students be separated into two different FHA sites.

“This building is not equipped for high school kids,” said Robbins. “It is not ideal for high school science classes, because we don’t have the [facilities and equipment] that we need for that. There’s some stuff you can’t do with portables [work stations]. We need more space.”

As for Welch, he said he’s pleased to hear that conditions have greatly improved at FHA. He wonders if the current environment might have made a difference during his time there.

“I chose to get involved with the suit because I wanted to do something to help other kids in that situation,” said Welch. “Nobody should be treated like we did.”

He said in retrospect that he wished he had taken his education more seriously. He hopes to return to school once he’s released from prison. To others experiencing behavioral problems in school, Welch advises:

“Put God first, accept being wrong, and strive to better and change yourself,” he said. “And listen to your parents. Stay off the streets.”

Chandra Thomas Whitfield is a 2011 Soros Justice Media Fellow.

Photos by Clay Duda/Staff

This story was originally published in the June-July 2012 issue of Youth Today.