Brittany Fisher grew up in the South End of Hartford, Connecticut, a tough neighborhood where gangs flourished.

When she entered South Middle School in 2002, other students found out her mother was a lesbian, and she was bullied. She became a fighter.

One afternoon in eighth grade, she stood outside the school with a group of students. Suddenly, several boys jumped her.

“Four of them were on top of me, hitting me,” she said. At that moment, staff from the after-school program ran out to rescue her.

One of them was Elizabeth Giannetta-Ramos, known as Liz, who had helped found the after-school program, the South End Knight Riders Youth Center in 1995.

Giannetta-Ramos protected Fisher that day, and she has helped to protect her long-term.

“Liz put me in all the after-school programs,” Fisher said.

South End Knight Riders was created as a place for kids to get off the streets, have an afternoon snack, do homework, play basketball and dance. It was a safe haven in a neighborhood caught in gang violence.

Fisher also was enrolled in summer camp, attended anger-management classes and had the support of adults who ran the youth center.

Looking back, Fisher realizes how it all could have been different.

“If it weren’t for Liz, I would be in jail, or in a gang, or on the street,” she said.

After Brittany graduated from high schoo, she got a scholarship to college.

Now 25 years old, she’s a newly minted social worker at Central State Hospital in Petersburg, Virginia.

Other friends from her youth weren’t so fortunate

“I escaped, but they didn’t,” Brittany said.

They remain in an impoverished neighborhood, barely making ends meet.

Elizabeth Giannetta-Ramos, community school director for COMPASS Youth Collaborative, reads to kids at Burns Latino Studies Academy in Hartford, Connecticut. As a teenager, she led the effort to establish South End Knight Riders Youth Center, where she worked and mentored youth including Brittany Fisher.

The widening gap between rich and poor

Brittany’s hometown is a vivid illustration of the gap between the rich and poor in America.

Hartford is the capital city of Connecticut, one of the most affluent states in the nation. The city is a half-hour drive from Yale University, a top college of the Ivy League.

And yet the Hartford-New Milford area is an area of concentrated poverty, with 51.9 percent of residents living below the poverty threshold.

The gulf between rich and poor in the United States is widening, increasing in 45 states between 2011 and 2016, according to the Opportunity Index, which bases its figures on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

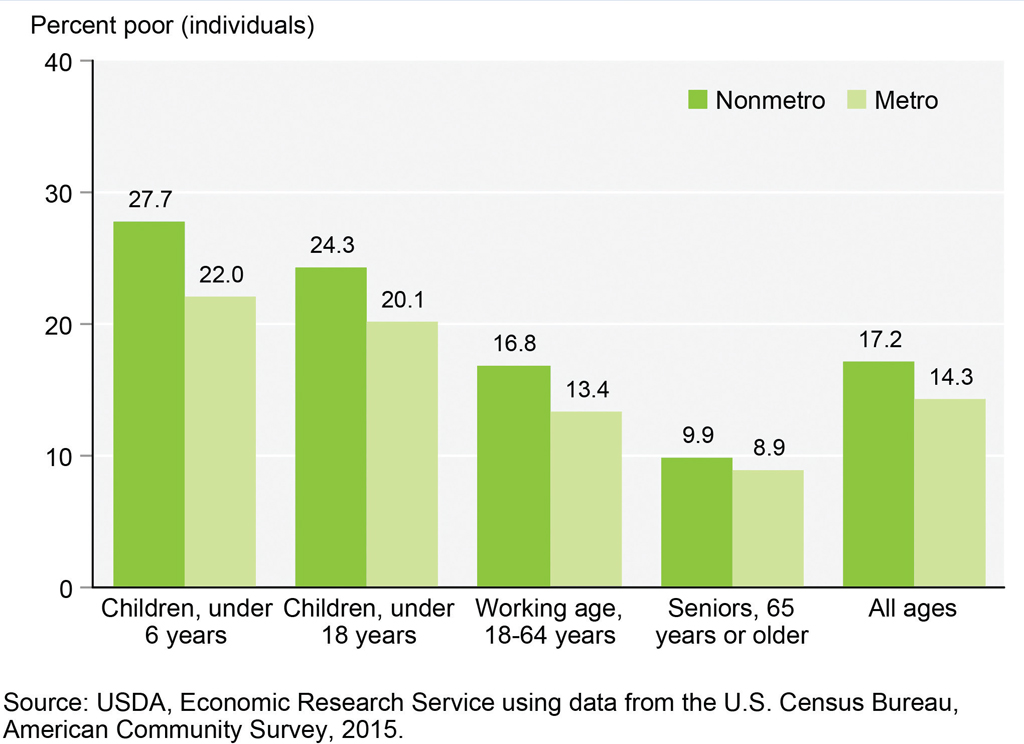

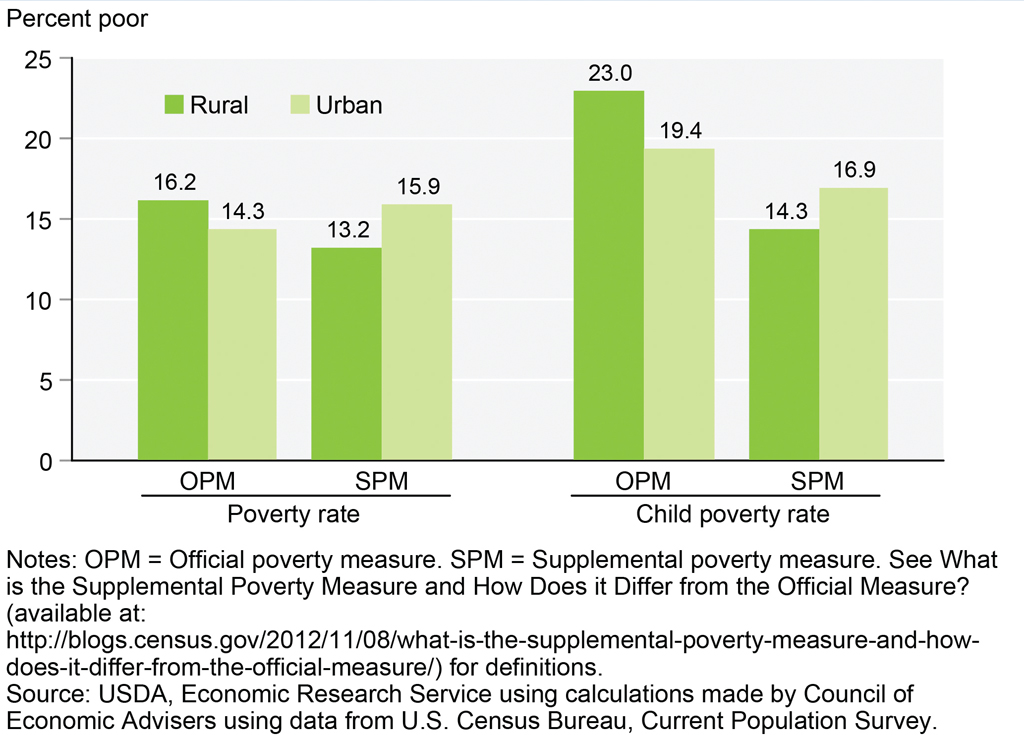

More than one-fifth of all children under 18 live below the federal poverty level, and a full 43 percent live in low-income households, defined as twice the poverty threshold, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty.

Since 2007, the number of children living in areas of concentrated poverty has risen from 8.6 million to 10 million, according to the Annie E. Casey Kids Count report, based on figures from 2011 to 2015, the latest available.

People who live in these areas face higher crime, go to less-adequate schools with higher dropout rates and have poorer physical and mental health, according to the 2016 Brookings Institution report, “U.S. Concentrated Poverty in the Wake of the Great Recession.” Their access to jobs is poorer, too.

Far more youth of color live in high-poverty areas: one in three African-Americans, one in three Native Americans and one in four Latinos, according to the report.

Dance has been one of COMPASS’ after-school offerings since it began as the South End Knight Riders Youth Center.

What American Dream?

The lack of opportunity for young people signals the evaporation of the American Dream, according to Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam and colleagues at the Saguaro Seminar.

The Saguaro Seminar is a gathering of scholars at John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. Their 2016 report “Closing the Opportunity Gap” said neighborhoods today are more segregated by income and have fewer institutions that provide a social safety net for youth.

Among those safety nets are supportive organizations outside of schools.

Kids in low-income households are far less likely than they were in the 1970s and ’80s to take part in extracurricular activities, according to the report.

By sixth grade, low-income kids have likely spent 6,000 fewer hours in enrichment activities outside of school than more affluent children, according to ExpandED Schools, a nonprofit dedicated to increasing kids’ access to enrichment.

“If you don’t have parents with time and income and transportation, it’s hard to get exposed to out-of-school opportunities that help you find your path in life,” said Gigi Antoni, director of learning and enrichment at The Wallace Foundation. “Kids who do have the opportunity, do better on almost every academic measure.”

They get into college, are successful there, graduate, have a family and a career, she said.

As kids grow older, a high number are disconnected from school and work.

In 2015, 13 percent of young adults ages 18 to 19 and 17 percent of young adults ages 20 to 24 were neither working nor enrolled in school, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

A call to action

Last year, participants at the Saguaro Seminar issued a call for action in five areas:

- Provide family and parenting supports

- Promote early childhood development

- Support k-12 education in and out of school

- Strengthen community institutions

- Provide on-ramps to successful work.

The report calls on an audience of local leaders and organizations to be as creative and experimental as the reformers of the Progressive Era in crafting solutions.

In addition, 40 local foundations joined together in the summer of 2016 as the Community Foundation Opportunity Network to develop solutions and serve as a hub for other funders, policymakers and institutions concerned about the opportunity gap.

After-school plays an important role, particularly in the context of a community-wide effort to provide wraparound support for youth, including tutoring and mentoring, and to provide a stronger school-to-work linkage.

Back in Hartford …

In Hartford, South End Knight Riders became an independent nonprofit organization in 2001 and changed its name to COMPASS Youth Collaborative in 2005. It works with the city of Hartford, United Way, Hartford Public Schools, the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving and other small foundations to reduce barriers to opportunity for kids in Hartford.

COMPASS provides a comprehensive after-school program serving 130 pre-k to eighth-grade kids daily in three Hartford schools. It also provides support for kids in need from an office in each school, figuring out a coordinated response to help students realize their full potential despite the opportunity gap. Support teams for kids include a COMPASS staff member, a teacher, guidance counselor and social worker, said Jacquelyn Santiago, COMPASS chief operations officer.

“We’re a deliberate partner that works with schools to remove barriers to learning,” Santiago said.

Schools have a food pantry, a clothing closet, mental health services and an in-school dental clinic. COMPASS brings in tutors when kids need them and is a resource for classroom teachers.

COMPASS also runs an anti-violence program called Peacebuilders, which serves 250 youth ages 13 to 18 per year. Hartford has a high rate of gang activity, and Peacebuilders mediates both individual and group conflict. lt works with youth who are at risk of being violent or becoming victims of violence and connects them with supports that help them develop a more positive lifestyle.

Forty percent of youth in Hartford are vulnerable to school dropout, lack of employment or becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence, according to COMPASS.

“Hartford is one of the poorest cities in the country,” Santiago said. “I grew up in similar circumstances to a lot of the kids,” she said.

She grew up in a housing project in Lawrence, Massachusetts, after her parents moved from Puerto Rico.

“We were living in poverty,” Santiago said. “I didn’t realize there were opportunities for me other than what I saw on a daily basis.”

An excellent student, Santiago was offered a scholarship to a private school in Andover.

“It was 15 minutes and a world away,” she said. “It was culture shock to say the least.”

The school was much harder, she felt out of place and she considered giving up many times, but teachers intervened and supported her.

“People reached out to me in my most needy moments,” she said.

Brittany Fisher also recalls the moments that made a difference to her life. She remembers how supportive adults helped her envision a wider future.

“A lot of children don’t know there’s more to life,” she said.

“I wouldn’t be here without my parents and the COMPASS program,” Fisher said. “It was so beneficial for me.”

“These programs are very much needed,” she said. They are valuable if they save one life or there’s one less gang member or teen pregnancy, she said.

COMPASS partners with schools to improve student performance, wellness and school culture. It provides tutoring and enrichment, and it coordinates other services such as dental care and family/parent classes to meet needs that could otherwise hamper kids.