Unemployment among teens and young adults is the highest it has been since the government started keeping records and represents conditions of a depression rather than just a deep recession. Perhaps more troubling, the effects of these depression-like conditions could have broad implications for these young people, including lower future wages, that could persist for a decade or more.

“We know that young people, especially young black men, are the first to feel the effects of the recession and the last to feel the benefits of the recovery,” said Thaddeus Ferber, vice president of policy at the Forum for Youth Investment, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit think tank.

Employment experience early in life, most experts say, is important because it provides young people with on-the-job training that translates into skills that can be leveraged in the marketplace. Some evidence suggests that high unemployment among low-income youth can elevate the crime rate and exacerbate other social problems, including poor health. And steep unemployment among 16- to 19-year-olds tends to affect their employment prospects and wage-earning potential as they grow older – especially those who don’t move on to higher education – which, in turn, can affect the work situation for young adults.

A loss of 4 million teen jobs

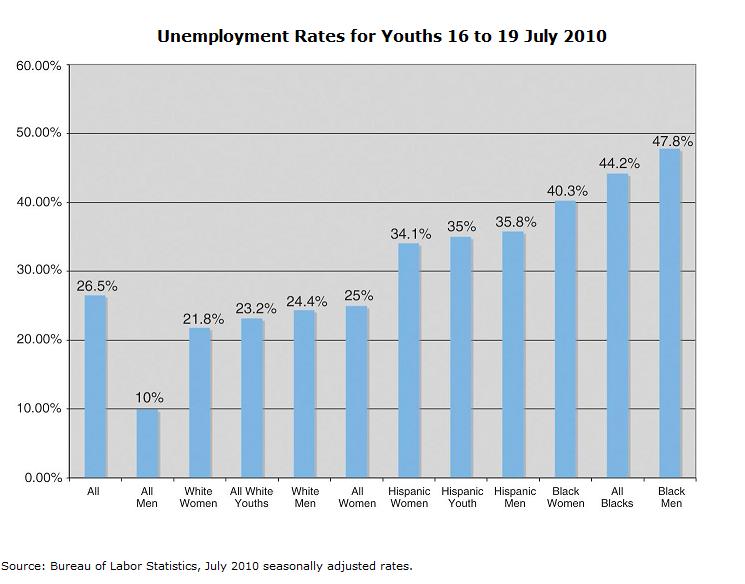

A young person pounding the pavement to find a job these days is likely to hit a dead end. The overall unemployment rate for all Americans stands at 9.5 percent, but the unemployment rate for youths between the ages of 16 and 24 in July was 18.6 percent. For teens between the ages of 16 and 19, the unemployment rate was a whopping 26.1 percent. The unemployment rate is computed by adding the number of people who are employed and the number who are looking for work and dividing that figure into the number looking for work.

But the unemployment rate doesn’t tell the whole story. It doesn’t count youths who want a job but instead have withdrawn from the labor market because they don’t think they’ll find one.

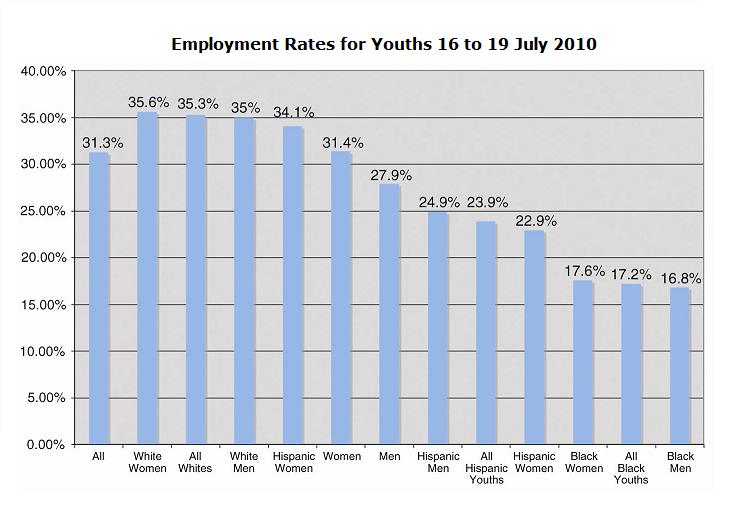

The employment picture – which experts use to get a truer picture of the young people who are actually working – is even more startling. The current employment rate for 16- to 19- year-olds, at 25.6 percent, is the lowest on record in more than 60 years, according to data collected by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The employment rate is simply the percentage of all persons in an age group who are working.

In June 1980, roughly 55 percent of 18- to 19-year-olds were employed, compared with just 36.2 percent of the same age group working today. The July employment rate for 18- to 19- year-old black men, 24.9 percent, was nearly 16 percentage points lower than in July 1980 (40.7 percent).

Looking more broadly at the job data for the past 20 years, employment rates for 16- to 19-year-olds peaked at nearly 50 percent at the end of the 1980s’ economic expansion. The rates dipped during the downturn of the early 1990s, to around 41 percent, but mostly recovered by the end of the decade, to a youth employment rate of 45 percent.

“This decade’s really been tremendously different,” said Joe McLaughlin, senior research associate at the Center for Labor Market Studies (CLMS) at Northeastern University. Youth employment rates dropped dramatically during the six-month recession in 2001 but continued to fall through 2004, he said, even as the economy recovered, albeit anemically.

When the 2008 economic shock hit, even more youths were pushed out of the job market. “We’re down like 19 percentage points just over this decade,” McLaughlin said. If the youth employment rate today were at the 45 percent level of 2000, he said, there would be nearly 4 million more teens working right now. “So the magnitude of this decline is huge, just over this last decade.”

Impacts on future earnings

The long-term effects of youth unemployment are real and lasting, according to Tim Savage, an economist whose dissertation on the subject led to an article, co-authored with Thomas A. Mroz, that was published in the Journal of Human Resources in 2006. Savage, using a sample from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, studied employment outcomes of about 3,700 young men who ranged in age from 14 to 19, from 1979 through 1994.

Over those 15 years, young people who experienced early unemployment continued to see depressed earnings for years, even a decade later, his research showed. While youths worked hard to catch up after stints of unemployment, mostly by accessing training resources, it wasn’t enough to combat the early spells of joblessness, Savage found.

“In 2002 U.S. dollars, at 2,000 hours per year,” Savage and Mroz wrote, “a six-month spell of unemployment at age 22 yields a $1,400 to $1,650 earnings deficit at age 26 (about 6 percent of what would have been urged withut the unemployment) and a $1,050 to $1,150 deficit (about 4 percent) at age 30, depending on the type of average effect one considers.”

“Now all that research was done in a context where we had not seen a recession as deep as this one, even going back to the ’82 recession,” Savage said in a recent interview. Likening the situation for youth today to a “tsunami,” Savage predicted “some pretty adverse outcomes from the current very high unemployment rate.”

Youth optimism persists

According to a July 2010 report by the Pew Research Center, “How the Great Recession Has Changed Life in America,” based on a survey of 3,000 people in May, young people remain more optimistic than adults about the future, said Paul Taylor, Pew’s executive vice president. “Despite the hard economic times that they are living through, this is a very confident generation,” he said.

Another Pew report, released earlier this year, on the attitudes of “millennials” – young people between the ages of 18 and 29 – also found these young people to be “more upbeat than their elders about their own economic futures, as well as about the overall state of the nation.”

While most youth remain largely sanguine about the future, advocates argue that policymakers should take action to offset the high levels of youth unemployment. Savage said his research shows that individuals, when faced with a “shock” of unemployment, will gravitate toward available training, which can blunt the long-term impact of joblessness. This may be particularly relevant for young high school graduates who do not move on to higher education, a group that Savage said are “most at risk for being permanently adversely affected” by early joblessness.

Federal remedies unlikely

Deborah Weinstein, executive director of the Coalition on Human Needs, said Congress should, at the “bare minimum,” provide funding to extend several American Recovery and Reinvestment Act investments that are ending this year. That includes $1 billion for youth summer and year-round employment – a fund the Senate has repeatedly voted down – and renewal of a Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program that 34 states, the District of Columbia and the Virgin Islands are using in part to subsidize employment for adults and youths under age 21.

Even with the prospects of congressional action on these and other items about as dim as a youth’s ability to find an entry-level job, advocates like Weinstein – whose organization released a report in late July called “The Recession Generation: Preventing Long-term Damage from Child Poverty and Young Adult Joblessness” – say it’s hardly enough.

“We need a comprehensive set of investments to provide more public and private jobs and the training and job-placement services that help young people get into those jobs,” Weinstein said, citing a proposal pending in the House called the Local Jobs for America Act as one possible vehicle. “We can’t pretend that we’re not in a dangerous period in terms of the ability of our young people to be part of a stable, prosperous workforce.”

![]()