If there is one idea that dominates the youth work and positive youth development fields, it is that every kid needs and deserves caring adults. The idea is held up so often – in education, social service, mentoring and prevention circles – you’d think there would be great clarity about what caring adults actually means. There isn’t. If it’s that important, we ought to do a better job of naming what we mean.

I think the central dynamic of a caring adult is the conversation, the two-way dialogue that engages both youth and adults and is sustained over time. And while many view these as conversation starters – “How’s it goin’?” “How’s school?” and “Wha’s up?” – they are actually conversation stoppers that give kids and adults a free pass for avoiding talking about anything substantive.

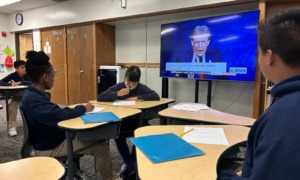

It’s one thing to sustain a conversation with a child; it’s a totally different deal trying to launch and keep up a two-way dialogue with teenagers. Robert Reich, the former U.S. labor secretary, recently wrote in an opinion piece about his relationship with his teenagers that adolescents are like clam shells. Most of the time they are closed tight. Now and then, they open up. When they do, Reich says, be there and take your best shot at keeping the shell open.

I think I now know the conversation that keeps the clam shell open. It is actually a script of six questions that can be posed all at once or across time. The questions can be used over and over again. Kids, once asked them, want to pose them to adults and, in fact, are eager to do so.

Let me explain first how these essential questions emerged. They grew out of a line of inquiry on human thriving, the process of being fully alive, of being in the world with energy, with eyes wide open, with an eagerness to learn, connect and contribute. In a model I am building with my colleague, Peter Scales, a developmental psychologist, there are three essential components in the thriving process: the identification of one’s spark, embeddedness inside several adult relationships that honor and nurture the spark, and opportunities – in community, family and school – to express it, to work it.

“Spark” is my metaphor for a person’s primary source of animating energy and intrinsic motivation. All youth get the concept of spark in a heartbeat; all youth want to name it; all youth want people to know it and places to use it. Still, youth typically say that no one has ever asked them to describe their spark.

The sparks of America’s young people fall into three categories. Some are talents or skills like writing or singing. Some sparks are things a person cares deeply about, like the environment, animals, serving community, world peace. And some sparks are qualities that one knows are special and of high value, like caring, empathy, peacemaking and tolerance.

Over the summer, the Best Buy Children’s Foundation sponsored and released a report, based on a national poll of 1,817 fifteen-year-olds (see http://www.at15.com), that put to the test the three-part thriving formula of spark plus caring adults plus opportunity.

The bottom line: only 7 percent of 15-year-olds have all three parts of the formula. The problem is not with naming one’s spark. The problem is in programs, schools, families and communities that fail to see it.

Our nation’s kids want and need the world to awaken to their gifts. They want a new conversation. Hence, my six essential questions:

What is your spark? When and where do you live your spark? Who knows your spark? Who helps feed your spark? What gets in your way? How can I help?

This dialogue has two dramatic consequences. It awakens something in kids. As important, kids will turn the table and want a shot at asking us the same questions. When this happens, we’ve begun to build authentic relationships with kids in which they give us as much as we give them.

I’ve been putting the questions to practice lately, as I speak to teachers and youth workers about these ideas. I usually ask adults to explore the six questions with the colleague sitting next to them and I’ve discovered something powerful. Teachers and youth workers get extraordinarily animated by this dialogue and usually report something like this: “I’ve been working with some of the same people for years, and until now, I had no clue about their sparks.”

All of us who work with kids need to practice the art of authentic relationships with each other in our schools and programs. Doing so will be the morale booster that sustains us in the work and makes each of us better at having real conversation with young people.

You’ll find that these six questions are not just for kids, but are for all of us.