Photo courtesy of Mya Petty/The Missouri GSA Network

Youth in St. Louis marched on Sunday from a local high school to the police department to raise awareness about school pushout during Dignity in Schools’ National Week of Action.

Activists concerned about disciplinary policies that force students out of school and into the justice system will gather in cities across the country this week to make their case for reform.

In Boston, they plan to fan out to ask their peers about their experiences with school discipline, results they will pass on to city school administrators.

In Miami, the community will gather for a Forum on Black Lives focused on local county and school board races to ensure school discipline is on the agenda.

And in Dayton, Ohio, organizers will release report cards that show how every school system in the state is performing on disciplinary measures, data that’s collected but not publicized by state officials.

The events are part of the Dignity in Schools Campaign’s 7th annual Week of Action to raise awareness about school pushout.

The campaign’s supporters argue schools are too quick to punish students harshly, especially students of color, students with disabilities, and students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender.

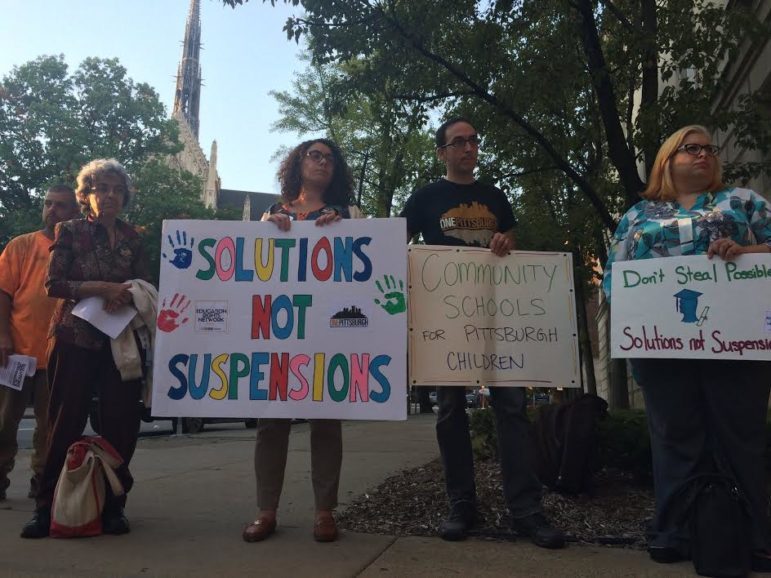

Photo courtesy of One Pittsburgh and Education Rights Network

In Pittsburg, supporters of the Solutions Not Suspensions Campaign spoke on Monday at a school board meeting about the importance of ending school push out.

Suspensions and expulsions can cause students to leave school and lose direction in their lives, ultimately ending up in the criminal justice system, a phenomenon known as the school-to-prison pipeline, they say.

This year, the national campaign will stress five key reforms:

- Shift funding from school police officers to counselors and peace workers;

- Fund and use restorative justice and mediation practices;

- Stop arresting and pushing students out of school, especially students of color, LGBT youth, youth experiencing homelessness and students with disabilities;

- Make sure officials focus on a healthy school climate as required by the federal Every Student Succeeds Act; and

- End paddling and other physical punishment.

Since the campaign launched a decade ago, communities are increasingly aware of the importance of paying attention to disciplinary policies, said Nancy Treviño, a spokeswoman for the campaign.

The federal government has released recommendations on discipline, cities and states have adopted new policies and media organizations are more likely to tell the stories of communities concerned about school pushout.

But, much work remains to be done, organizers say. The politics of every community vary, making the implementation of policies that stress alternatives to suspension or promote restorative justice the next hurdle for advocates, Treviño said.

Ten years ago, school administrators had to be introduced to concepts like school pushout, said Ruth Jeannoel, lead organizer at Power U Center for Social Change in Miami. Now they know more but still sometimes have to be prodded into following through on proposed policies or informing students of their rights, she said.

“There’s a lot of work that has happened, but of course there’s a lot more to do,” she said.

In Boston, advocates long have enjoyed a good relationship with city school officials, said Tina-Marie Johnson, a youth worker at Youth Organizers United for the Now Generation.

Each year, advocates share their findings from the surveys youth take of their peers to make the case for where reforms still are needed. And organizers update the survey each year, to be sure they’re addressing new issues that may have arisen and capturing as much data as they can about whether some populations of students face harsher consequences than others.

“We want the conversation to be inclusive of all members of the school community, especially those who [are] affected the most,” Johnson said.

Hashim Jabar, director of the West Dayton Youth Task Force, said data is critical for making the case to school, local and state officials, but he also wants families to spend time understanding what’s happening in their local schools.

“The community as well needs to know more and stand up for themselves and take the information and use it to be empowered,” he said.

In additional to the local events, a national event with speakers and music is planned for tonight in Pittsburgh, with a livestream available for those in other locations.