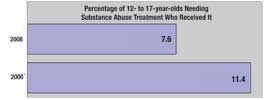

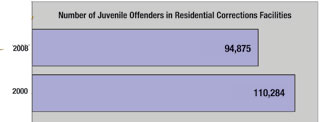

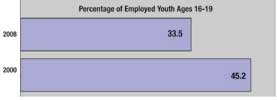

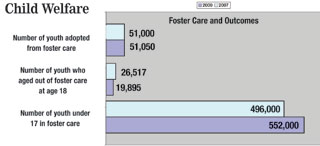

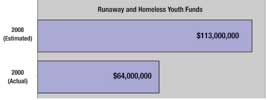

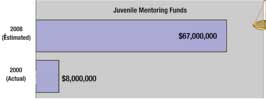

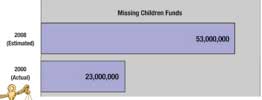

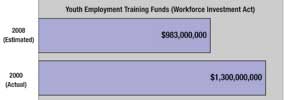

On these pages is a sampling of changes in youth well-being and youth-related federal spending during the Bush administration. Both supporters and opponents of the president will find evidence for their own assessments.

Sources: All federal budget information is from the Budget of the United States Government, fiscal 2002 and 2009, U.S. Government Printing Office. Youth data are from various sources, including: U.S. Census Bureau; Center for Labor Statistics; U.S. Children’s Bureau; U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Education; U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

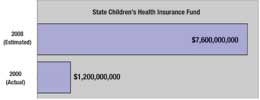

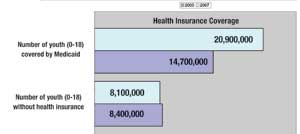

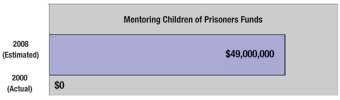

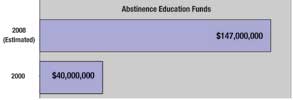

The top bar is 2008 (estimated) spending and the bottom bar is 2000 (actual) spending by youth-related program.

Six Key Changes

President Bush’s impact on youth services can also be seen through six strategic actions by his administration:

Permitting flexible funding in child welfare: The Bush administration and some Republicans in Congress wanted to let states spend federal child welfare money on a larger universe of options, free from the standard restrictions. Democrats saw this as a carrot with a big stick: losing the protection of guaranteed amounts of entitlement or formula funds, such as Title IV-E and IV-B foster care money. The administration found the idea to be a tough sell, but Florida accepted a waiver to use its IV-E funds more flexibly. The state invested more money in family preservation efforts, which some observers say helped to improve Florida’s foster care system.

Blocking SCHIP: In the face of a big movement to expand the State Child Health Insurance Program, Bush twice vetoed legislation to do so. The White House argued that expansion would crowd out private insurers. The argument was mostly moot; cuts caused by the Deficit Reduction Act (spearheaded by Bush and congressional Republicans) crippled the ability of states to enroll more children in the program. In January, Congress again moved legislation to expand SCHIP.

Reining in AmeriCorps: The program accepted more participants than it could pay in 2003, a misstep that led to the revelation that the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) had bungled its finances for years. CNCS Director David Eisner balanced Congress’ demand for stricter enrollment and matching policies with the pleas of practitioners, who did not want to see regulations prevent good programs from using AmeriCorps volunteers. Bush had previously pledged to increase the number of AmeriCorps volunteers, but the number shrank under his administration. President Barack Obama has pledged to increase the number of participants in AmeriCorps.

Expanding FYSB: Early in Bush’s tenure, his first Health and Human Services secretary, Tommy Thompson, decided that more youth programs should be brought under the scope of the Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB), a division of the Administration for Children and Families (ACF). That helped the FYSB budget more than quadruple from $88 million when Bush took office.

Much of the increase came when the Community-Based Abstinence Education (CBAE) program, along with funds for abstinence programs under the Social Security Act and the Adolescent Family Life Act, were moved to FYSB from the Health Resources and Services Administration. The health resources staffers didn’t mind; they had struggled to manage abstinence education as a medical program in the face of criticism from the public health field. ACF Commissioner Wade Horn was happy to defend those programs at FYSB. Also added to FYSB was the Mentoring Children of Prisoners program.

Initiating Child Family Services Reviews: Amendments to the Social Security Act in 1994 mandated that the federal government examine state child welfare systems based on outcomes for children known to the system. It wasn’t until Bush took office that the process began. Every state failed its initial review and submitted an improvement plan; second-round evaluations are in progress. There is much debate about the methodology of the reviews, but the move toward outcome-based assessments is noteworthy.

Moving YouthBuild to Labor: The program’s architect, YouthBuild USA President Dorothy Stoneman, says she backed the transfer of the program from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to the Department of Labor, because the Bush administration told her there was more room to grow at DOL. However, YouthBuild’s funding tanked.