|

| Click on chart to open PDF version. |

Before the hammer fell last year, a federal demonstration project to guide disadvantaged youth to successful adulthood had shown some exciting results: In five sites across the country, youths who appeared likely to drop out of school or spend a lifetime bouncing among low-end jobs were learning new job skills, earning paychecks, getting diplomas and GEDs and getting into college.

Then the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) decided not to fund the third year of its Foster Youth Demonstration Project. The sites prepared to scale down and wondered how long they could last.

That was until the evaluator, Casey Family Programs, stepped in, devoting at least $2 million to continue the project for at least another year. In July, a final evaluation report showed why: Aside from specific educational and employment gains, the projects demonstrated replicable youth work practices for youths who have been in foster care or are otherwise at risk for adulthoods marked by poverty and incarceration.

Youths in child welfare benefited greatly from close relationships with adults outside the child welfare system; pickiness in hiring staffers paid off in quality, even at the cost of leaving positions unfilled for longer periods; partnerships between youth organizations and job training services, juvenile justice systems and community colleges bore fruit; and more job training resulted in measurable increases in employment.

“This is such an important way to demonstrate how to serve this population of youth,” said Sue Badeau, a foster care expert who initially served as a consultant on the project for Casey Family Programs.

Still, the overall experience has left some bad feelings. “It was great that [DOL] started it, but it was just irresponsible for them to pull out,” said Jack Wuest, executive director of the Alternative Schools Network in Chicago, one of the five demonstration sites.

Or maybe it’s a good example of public/private partnership. One DOL staffer involved in the project called it “a great success.”

Strong Start

Among the laudable aspects of the initiative was that it was a rare example of research affecting public policy. In 2003, a panel of youth experts delivered to President Bush a long-awaited “White House Task Force Report on Disadvantaged Youth.” The next year, the DOL’s Employment and Training Administration took one of the report’s recommendations and created the Shared Youth Vision Federal Collaborative Partnership – a joint effort by several federal agencies to help needy youth transition to adulthood.

The Foster Youth Demonstration Project was one of the partnership’s “very first investments … to target resources to young people in foster care,” said Eric Steiner, employment adviser for Casey Family Programs.

The project worked like this:

In September 2004, DOL offered each of the five states with the nation’s highest populations of foster youth $400,000 a year, for a maximum of three years, for demonstration projects addressing the high rates of unemployment, dropping out, homelessness, health and mental health problems, substance abuse and incarceration among 16- to 21-year-old foster youth and foster care alumni.

Several studies have documented the poor life situations of youths who leave foster care. They are more prone than other youth to be incarcerated, become homeless and live in poverty; they are less likely to earn high school diplomas and college degrees. (See box.)

The states had to conduct their projects in cities with the highest concentrations of foster youth: Pasadena and South Central Los Angeles, Calif.; Chicago; Detroit; Houston and New York. The states also had to find $400,000 in matching funds each year. They tapped state funds from the federal Wagner-Peyser Act and the Workforce Investment Act, local- and state-level funds paid out by the federal Chafee Foster Care Independence Program, local child welfare budgets, and state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds.

The services were provided by partnerships of government and private agencies, including nonprofits.

Program Models

The funding allowed the sites to build or expand models of comprehensive support for youth transitioning to adulthood, with such services as individualized job placement, life coaches, housing and college tours.

• Los Angeles/Pasadena – The “California Model” had youth working through six sequential modules focused on intake/eligibility, employment, academics/education, training, financial literacy and job placement/retention.

• Chicago – “Project New Futures” included enhanced diploma/GED programs, post-secondary enrollment and job training services already provided by 13 schools in the Alternative Schools Network, and hired additional full-time “transition specialists” and a project coordinator dedicated to supporting youth after high school.

• Detroit – “Creating Independence and Outcomes” launched an education lab, began providing mentors and peer-to-peer support, and hired an educational coordinator and tutor.

• New York – “Passport to Success” assigned a life coach to each youth and subcontracted with The Door, a nonprofit youth-service organization, to provide career exploration, paid work experience and cross-agency meetings.

• Houston – “Preparation for Adult Living,” already in place at the Houston Alumni and Youth Center, brought in additional partners focused on postsecondary education and work force development, and paid youth to attend a work-readiness course.

The sites served 1,058 youths, varying from 127 in New York to 358 in Houston. The youths were predominately black (71 percent), between the ages of 17 and 21 (81 percent), female (58 percent) and in foster care (56 percent).

Early Results

Although the DOL required the sites to submit aggregated quarterly data, it did not provide a mechanism for doing so (other than to encourage the sites to track data on Excel spreadsheets) or meaningful technical assistance on definitions of data elements. It also failed to appropriate any funding for an evaluation,

In May 2005, Casey offered to evaluate the project at its own expense. “Our initial attraction was to find out what works,” Steiner said. “Not only for internal use at Casey Family Programs, but … to help all jurisdictions realize the resiliency and potential of serving foster youth through the WIA [Workforce Investment Act] system.”

Casey enlisted the Institute for Educational Leadership (IEL), the Johns Hopkins University, and consultants Badeau and Paul DiLorenzo as evaluation partners. Within four months, the evaluation team notified the sites it would be conducting site visits, document reviews and phone interviews in addition to the DOL data reporting requirements.

Once the DOL funding for the project ended, Casey launched an online data collection tool, designed in collaboration with staffers at the demonstration sites, to help the evaluators capture more nuanced data than the rigid DOL measurements allowed. That database, call EMPLOY, went on line the first of this year.

(The final evaluation report said none of the sites believed the outcomes or measures as defined by DOL fully reflected the progress of their youth.)

“We wanted to make sure that we accurately reflected the work that was going on at the sites,” said Kirk O’Brien, the Casey director of foster care research who developed the database. “A lot of effort went into the data collection to make sure the data were valid and spoke to the story of the youth.”

The first evaluation report, produced by IEL using only the measures dictated by DOL, was released in March 2006. It said “the sites are beginning to engage participants in first-time unsubsidized employment and … educational activities” through job placements, diplomas and GEDs and post-secondary enrollment.

That report noted that the “potential for sustainability” would be greater if DOL continued funding for a second year, so the sites could fully implement their programs, bring on more partners and demonstrate more positive outcomes for youth – components the sites must “have in place in order to secure the [non-federal] funding needed to continue.”

The second-year report, using a mix of DOL measures and newer data from site visits and interviews, was released in May 2007 and showed more gains for youth as well as program refinements made by the sites.

But two months earlier, DOL had informed the sites by e-mail that it would not fund them for a third year.The evaluation data “did not figure” into DOL’s funding decision, a Labor Department spokesperson said in an e-mail to Youth Today.

DOL Pulls Out

“It was basically abandoning foster care kids,” said Wuest, of the Alternative Schools Network. “They were left homeless, without a program.”

Although DOL had urged the sites to develop sustainability plans, several were unprepared. The news gave them a “significant jolt” at a time when they were refining their models, according to the final evaluation.

In Chicago, Wuest said his program delayed hiring a transition specialist who would have worked one-on-one with youth.

The demonstration site in Houston, The HAY Center, looked for more affordable facilities. Word of the center’s possible move got around, and by the time a new lease was secured, the report says, “many of the [358] youth had drifted away … and the Center had to work hard to attract them back.”

At the Foothill Workforce Investment Board site in Pasadena, operations manager Dianne Russell-Carter’s “Plan B” was to keep things running temporarily by using her county’s summer youth employment funds.

Sustainability “was an underlying concern from the very beginning,” Russell-Carter said. “We, as well as the other sites, kept telling DOL ‘we can talk about sustainability, but it’s going to be very hard for us to get this kind of money … in that small amount of time.’ ”

A DOL staffer told Youth Today that the withdrawal was “a natural progression,” given that the federal agency was in “a partnership” with a private entity that had expressed interest in the project.

“The government isn’t there for the long haul. That’s not what we’re ever about,” the staffer said.

What DOL described as a partnership wasn’t viewed quite that way by Casey. Casey had approached DOL and offered only its evaluation services at no cost to the federal government.

But by April 2007, Casey was talking with each of the five sites about possibly continuing the funding.

“Casey did not offer to pick up the funding [for the program] until DOL made it quite clear that the funding was not going to continue,” said Badeau, now director of systems analysis for Casey. “It was not like, ‘Well, you know, we’ll start funding it if you guys decide not to.’ ”

But a year earlier, Casey Family Programs had unveiled an ambitious commitment to foster care children and their transition to adult life. Under a strategy called “20/20,” Casey pledged to invest $1.67 billion to “improve the lives of children in foster care and ensure successful transition to adult life.”

The Foster Youth Demonstration Project fit that strategy. By July 2007, Casey was funding all five sites and had agreed to continue funding as long as the sites worked with its consultants to develop long-term sustainability plans using public and private resources.

Promising Results

The final evaluation, issued in July, reflects a full complement of DOL outcome measures and monthly participant update reports from the sites, along with two rounds of site visits and one round of phone interviews for each site.

Among the final report’s key findings:

• Staff relationships with youth – Youth overwhelmingly said they most valued the individual staff members who worked directly with them, and being able to engage in those relationships outside of a traditional child welfare agency. Those connections were made possible by low caseloads, mentoring relationships for the youths, motivation and staff accessibility.

The results show that helping foster youth prepare for independence “can’t just be a child welfare services function anymore,” Badeau said. “The youth don’t want it that way, it’s not effective, it’s not developmentally appropriate for where they’re at in their life cycle.”

• Program design and services – All of the sites continually reformed their programs as they gained experience with youth. Most programs dropped highly structured models that tried to address the needs of the participants as a cohort in favor of a more individualized, open-entry/open-exit approach.

• Program staffing – Good staffing decisions limited turnover at all of the sites, despite low pay. For example, Antoinette Wirth of Employment & Training Designs, the local demonstration site in Detroit, said her shop took up to six months to hire staff for the project.

“We worked especially hard to pick the right people, because we wanted to make sure we had people who really wanted to do this,” Wirth said. “We got a lot of applications from people in child welfare, and I don’t think we hired anybody. Even during the interviews, we couldn’t get them to think outside the box.”

• Program partnerships/collaborations across agencies – The four sites whose program administrators were employment-based agencies struggled to build collaborative relationships with child welfare systems.

Casey’s Steiner said such difficulty was understandable, given the fact that “child welfare systems are often overwhelmed with the very serious issue of child safety and less focused on transitioning youth.” All sites reported at least some success in accessing state Chafee funds through their child welfare systems.

On the other hand, several sites developed strong partnerships with Job Corps, juvenile justice systems and community colleges.

• Job placement and follow-up – While the sites had little difficulty placing youth in entry-level, temporary or part-time jobs, limited post-placement follow-up with employers and youth kept job retention rates low.

• Time in the program – The more calendar quarters in which youths received services, the more likely they were to achieve positive outcomes. For example, only 8 percent of participants who received no job training got jobs, compared with 32 percent of those who received one to three quarters of job training, 69 percent of those who received four to six quarters and 100 percent of those who received seven to nine quarters.

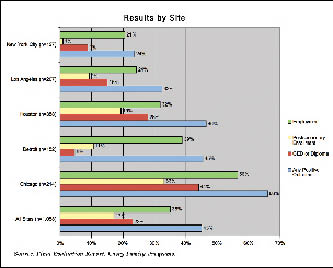

Among specific gains across the sites: Twenty-three percent of the youth attained a GED or high school diploma, 17 percent enrolled in post-secondary education, and 35 percent had jobs – figures all well above the averages for youth who’ve been in foster care. The outcomes varied greatly among the sites, and were traced to the program models, the characteristics of the youth and the number of quarters the demonstration was running at each site.

The Future

Casey spent $2 million on the project last year, in addition to the cost of the ongoing evaluation, Badeau said. She said Casey anticipates that amount will decrease as the sites begin to achieve sustainability.

How will they do that?

“We’re looking at a couple of different angles,” said Wuest of Chicago’s Alternative Schools Network. “One is the [federal] TRIO programs. Maybe we’ll talk to people here at the community colleges.”

Shannon Ramsey, a policy analyst with the Texas Workforce Commission – the state conduit for the Texas programs – said the commission plans to use TANF funds to continue funding the original site and three more.

The programs might have to move quickly. Ramsey said that last month, a Casey official told her that the original demonstration sites would each see a 20 percent to 25 percent reduction in funding next year. Casey spokesman Norris West told Youth Today, “It would be premature for me to discuss any budget matters,” because the 2009 budget hasn’t been approved.

“We’re looking at it one year at a time to ensure that these sites can be stable and that we can continue to get the value of the data and information,” Badeau said.

Contact: Casey Family Programs (206) 282-7300, http://www.casey.org. The evaluation reports are at http://www.iel.org/programs/casey.html.